Travis Somerville: Homeland Insecurity

Golden Thread Gallery, Belfast, 4 August – 22 September 2018.

In Fourth year English Literature, we had to read A History of the World in 10½ Chapters. One tends to try to forget these things quickly, and with the exception of this book and a (perhaps rash) aversion to Shakespeare, I succeeded. A form of Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa featured in that book, as it does here, in Travis Somerville’s solo exhibition at Golden Thread Gallery.[1]

The reference to this event/painting/event-painting in Barnes’ novel was my first encounter with The Medusa (having presumably not reached French Romanticism in that other educational stalwart ‘From Giotto to Cezanne’). What I do remember about this book is – across those 10½ chapters – the recurrence of boats; empathy and altruism or the lack thereof; the concept of ‘the little guy’ (in this instance a woodworm): the one who ultimately rocks (or eats) the boat (or the church). The book was criticised for its postmodernist disjointedness and that every human character appeared to be a cipher (aren’t they all though, really?). It all came rushing back to me when I entered the exhibition and met The Raft (2017), Somerville’s octaptych interpretation.

According to critic Jonathan Miles, the raft carried the survivors “to the frontiers of human experience. Crazed, parched and starved, they slaughtered mutineers, ate their dead companions and killed the weakest.”[2] In addition to these horrors, the colonial land-grabbing of Senegal by the French (and the general incompetence of these seafaring bastards) there are echoes here of every racially-aggravated disaster in contemporary America: the elite saves itself, the strong murder the weak and the weak shed their humanity to survive or drown in agony at sea. This is the structural racism that – most notably – enabled the desperate, impoverished and violent circumstances post-Katrina in the Louisiana Superdome amongst countless other scenarios.

In one of the panels the word ‘peckerwood’ floats in the Atlantic, visually analogous with the Hollywood(land) sign but contextually, geographically and culturally removed. I had to google this word, much as I think most UK-based viewers did when Miz Cracker showed up on RuPaul’s Drag Race season 10 (and declared that she was “just like the snack and the racial slur – thin, white and very salty”). According to the Urban Dictionary, a peckerwood is “a rural white southerner, usually poor, undereducated or otherwise ignorant and bigoted, the term gained popularity in the deep south during the early twentieth century and was meant to be derogatory.” [3]

On one panel, a disembodied Black male head dangles from the forestay, wearing a knotted Old Glory and sporting an afro of Dante de Blasio proportions, while another section of the composition features a disembodied white male head. It’s a side profile, but I’m pretty sure that’s Hitler, bruised and bandaged, and with a neck that withers into a snarled metal twiglet before evaporating into unprimed canvas… like Oscar Isaac in Ex Machina (2015) finally went too far. I’m not going to pretend that I know what it means. Aside from this oddity and more general cultural specificities, the pop-cultural references translate thick and fast throughout.

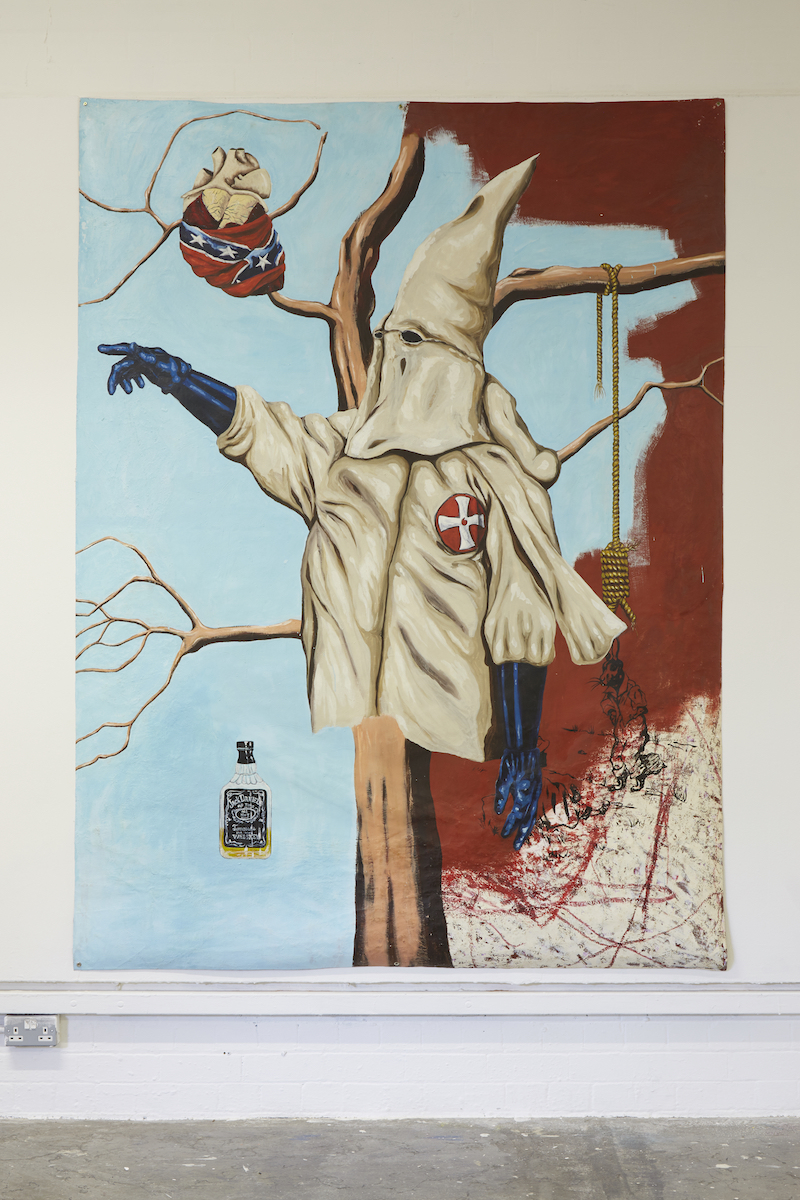

Confederate flags, bobbing bottles of bourbon, desaturated US flags, collages assembled from ‘The Sportsman Calendar’ and KK Klansmen in their dunce’s hats: this is the iconography of Southern US culture. Somerville was born in Atlanta, Georgia, to white civil rights activists – an Episcopal preacher and a schoolteacher [4] – and grew up in various cities and rural towns throughout the South.

Now based in San Francisco, the artist’s studio is in the former Naval Shipyard at Hunters Point which sits atop “a toxic waste dump and just yards from a former nuclear research laboratory that handled, and significantly mishandled, large amounts of the most dangerous and long-lived radioactive poisons produced during the Cold War.”[5] It was also – possibly unsurprisingly – a traditionally Black and Hispanic neighbourhood, fostered through years of redevelopment and tech sector intrusion which pushed these communities to the city’s frontiers and a literal half-life.[6]

Racist representations, which are peppered amongst this grouping of paintings, sting – they are sharp, not blunt, weapons. Somerville’s inclusion of caricatures of First Nation peoples in his work, clearly drawn from a childhood source, remind us that so many popular family cartoons of the 20th century depicted racial stereotypes – Disney in particular is riddled with slurs. Presumably contemporary cartoonists of everyone from Muhammed to Serena consider this their legacy or justification.

These paintings are the opposite of nostalgic. Their currency is palpable: dredging uncomfortable truths for which there is no yearning to return, but the acknowledgement that they are already/still here. This work gives a long, hard, uncomfortable stare at the phrase ‘post-racial society’. I’m not even sure how Somerville selects the content for his paintings, given the profusion of events, images, articles and statistics that could all be relevant. I feel like he could make a million paintings, just as I could write a million words about them.

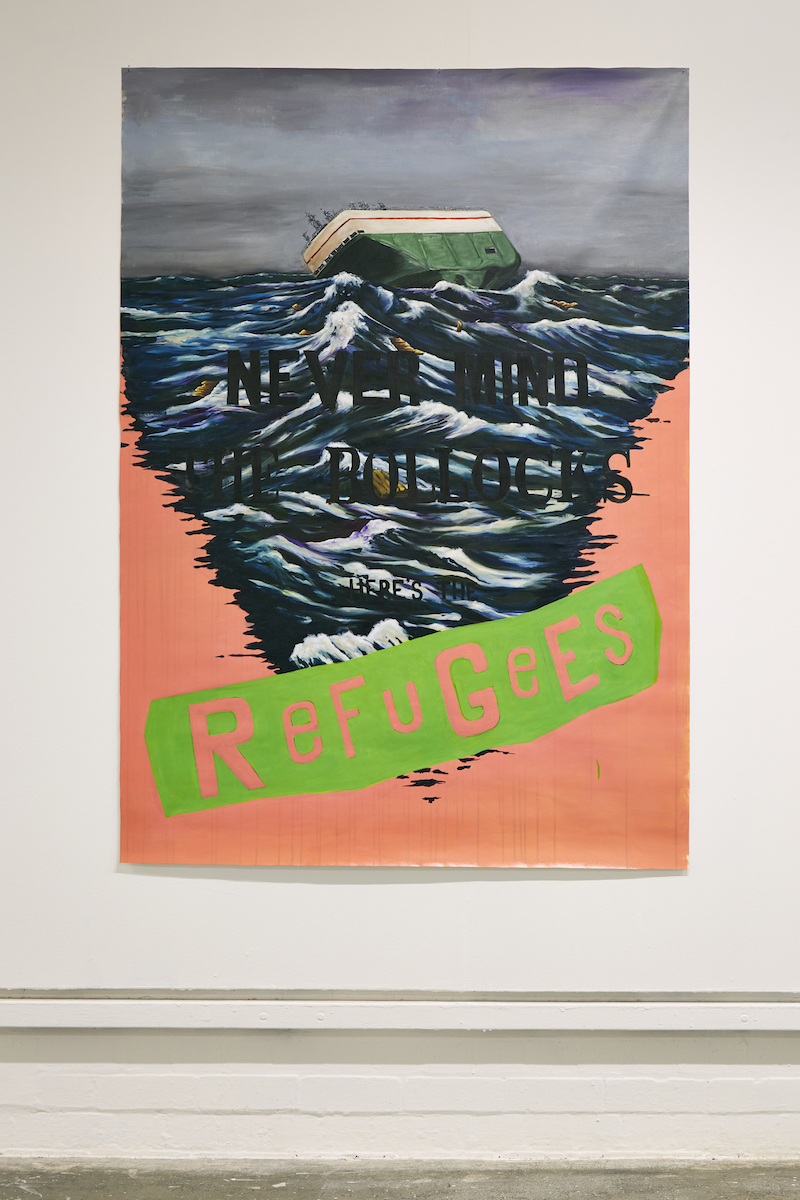

Across the (western) cultural spectrum, Childish Gambino’s This is America has notched up 391,476,403 YouTube views at the time of writing. Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017) returned sevenfold on its original budget (255.5 million USD box office). Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People about Race is a Top 5 Sunday Times Bestseller and has won numerous non-fiction book of the year accolades. Beyond the subjects, the extent of consumption around Black cultural capital indicates the opposite of an equitable society. The body blows delivered by Warsan Shire in her poem Home resonated in a way that other more popular media have yet to achieve, with this line in particular making it to the unlikely front pages of the UK’s print media:

no one puts their children in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.

A contemporary view is that Gericault’s painting was a manifesto against slavery, and the monarchy that enabled it; the raft’s occupants finally equal in the face of death. Somerville paints boat after boat. Bodies of water either appear swampy, with rowing boats occupied by anonymous Klansmen (who have named their ships جشع – Arabic for Greed), or they are deep, stormy and treacherous. Where boats are not explicitly included, they are implied: a young woman in a headscarf wades through knee-deep water holding a sole suitcase aloft. A young white girl stands in a river or lake, gripped firmly by an adult male (family member?) in what is either/both some sort of baptism ritual or an incident of domestic violence. Structures such as oil rigs and pylons are painted manifestations of the things deemed good enough to bring from other countries to ours: “as the world has become borderless to ‘flows’ of capital, the movement of migrant bodies is restricted as never before.”[7]

A series of three paintings depicts girls or young women who are deliberately un-centred in a landscape – situating them both anywhere and nowhere at the same time. Some of these kids have faces like early Lucian Freud paintings. Too-big eyes and individually rendered hairs. There’s also a touch of Käthe Kollwitz or even early Rita Duffy about them. These white(ish) kids are the ones who speak less to me amongst the selected works, but who might have the cross-cultural kudos necessary to remind the 57% of the Electoral College that secured Trump’s success (and the 52% of Brexit voters) of the white migration once deemed essential in the name of imperialism suddenly became threatening when challenged, reversed or taken too far; a tipping point whereupon British colonialism or American ‘manifest destiny’ translated into Nazi Lebensraum.

They’re drawn onto canvas once hewn for other purposes: feed bags and enormous cotton-picking sacks. One of these faces, Exiled (2017), could be contemporary (Syrian perhaps? There’s somehow an inference that this is a child of colour), but also affixed to the canvas are historical Soviet epaulets.

Back to ciphers.[8] I’m not qualified to judge how people should define their backgrounds or experiences. But I do feel that recognition of these symbols, stories and characters prompts debate around the universalising of experience, for both good and not-so-good ends. Zadie Smith refers to it as a ‘gag’: “whether they like it or not, [black or white] Americans are one people”. Yet Varaidzo rightly asserts: “[there is] no stereotype that can accommodate the vast array of personalities and histories and ethnic backgrounds that Black people possess.”[9]

I wish Golden Thread Gallery had brought more of this work here to Belfast. If some of the paintings were being exhibited elsewhere then that’s OK: wait until a bigger presentation can be assembled. I understand that pairing painters in separate-but-related shows seemed like a good way to provoke dialogue, but there is more than enough work in Somerville’s repertoire to justify a more substantial presentation, not to mention a return airfare from San Francisco. There are more boats, more disembodied heads and limbs. We should have seen the painting that features Scout Finch’s/Harper Lee’s most powerful words scrawled across its surface: There’s only one kind of folks. Folks.[10] Yeah, it might be hammering home the message for audiences but I think the general appetite for hammers over feathers can accommodate it.