Patrick Redmond, All Possible Worlds

Periphery Space, Gorey, 15 – 29 June, 2018

The chalky, many-windowed warren was empty but afforded sight of exterior surrounds, where young people, students in summer maybe, congregated intimately on grass verges at picturesque intervals. The emotional cocktail of schooldays seemed to lie dubiously in wait. Within, Patrick Redmond’s installation at Periphery Space announced itself with palpable ambivalence, forward and aloof, not quite a pinch nor a prod. Four rooms of grainy sunlight – walls sparsely sumptuous, heavy with collage, plasterwork and painted objects – solicitously impressed an ostensible hesitancy. The accompanying text, by Aodhán Rilke Floyd, relates the title All Possible Worlds to Voltaire’s Candide, and the contention that this is the best of all possible worlds. That notion may have relevance to Redmond’s work – to the extent that some of the anguish in tested dogmatism may characterise the introspection of institutional specialists, expert in received methods, attempting to see beyond their instruments.

From hazy introductions a forbidden spectacle emerged, an involved, hermetic practice, its glimmering facets growing infused like appendages. Cue an intuition of the artist present but gagged, fearful witness to helter-skelter of their unwitting instigation. The performers peacocked from mutually flattering vantages – modest mishmashes, two in threadbare book covers, one its reddish rear splayed and painted; dolloped pats of grey plaster and splish-splash drawing, windows on antiquarian nebulae; beefy collages of hot curly cut-outs in beach ball and umbers; canvases attesting slow effacement. Closer attention levelled this cornucopia to a blanket of dense, conspicuous relationality, its articulation a luscious network. Process pervaded – of collage and figuration inflected by European Baroque. Material attributes were collaboratively amped, an expansive, functional body. The overbearing demonstrativeness of this integrality, however, occluded any impetus or agency of materiality which may otherwise have been exerted.

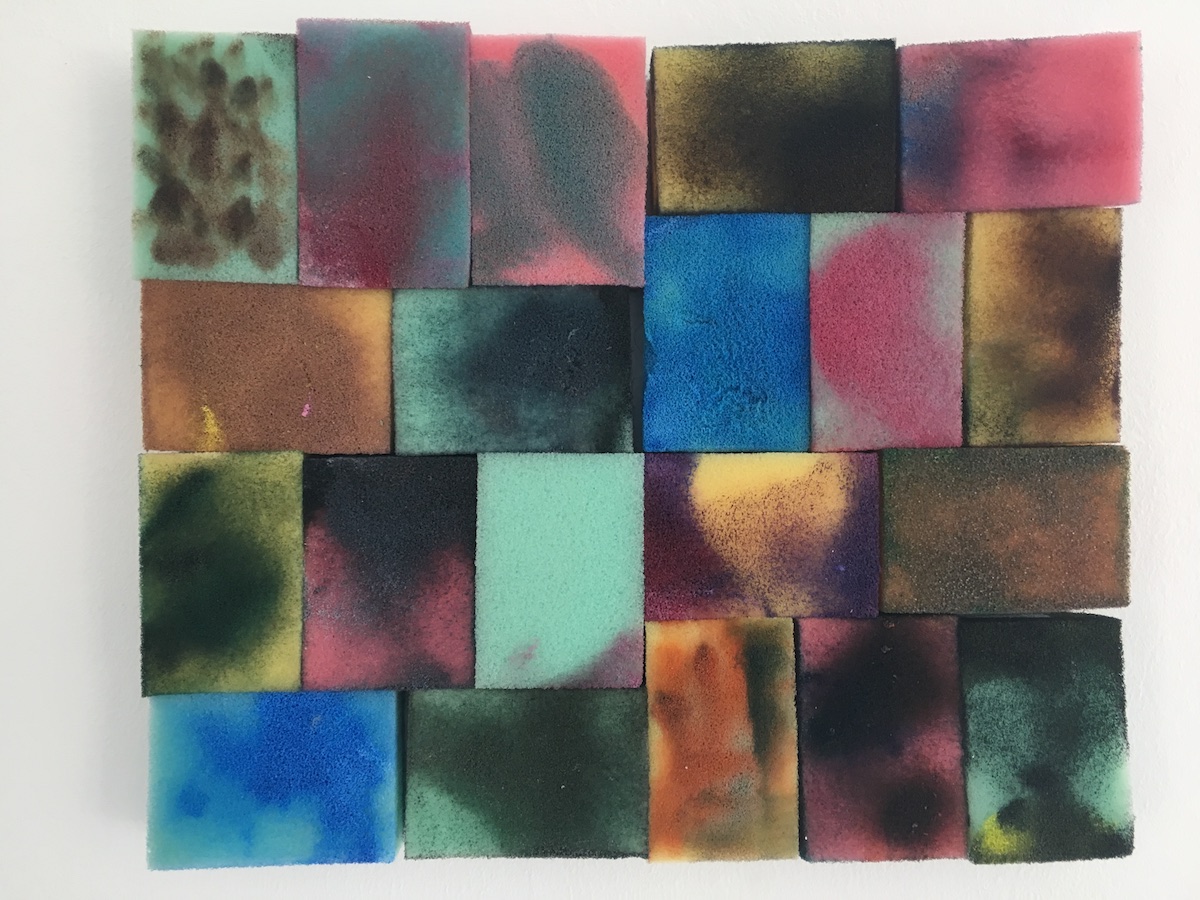

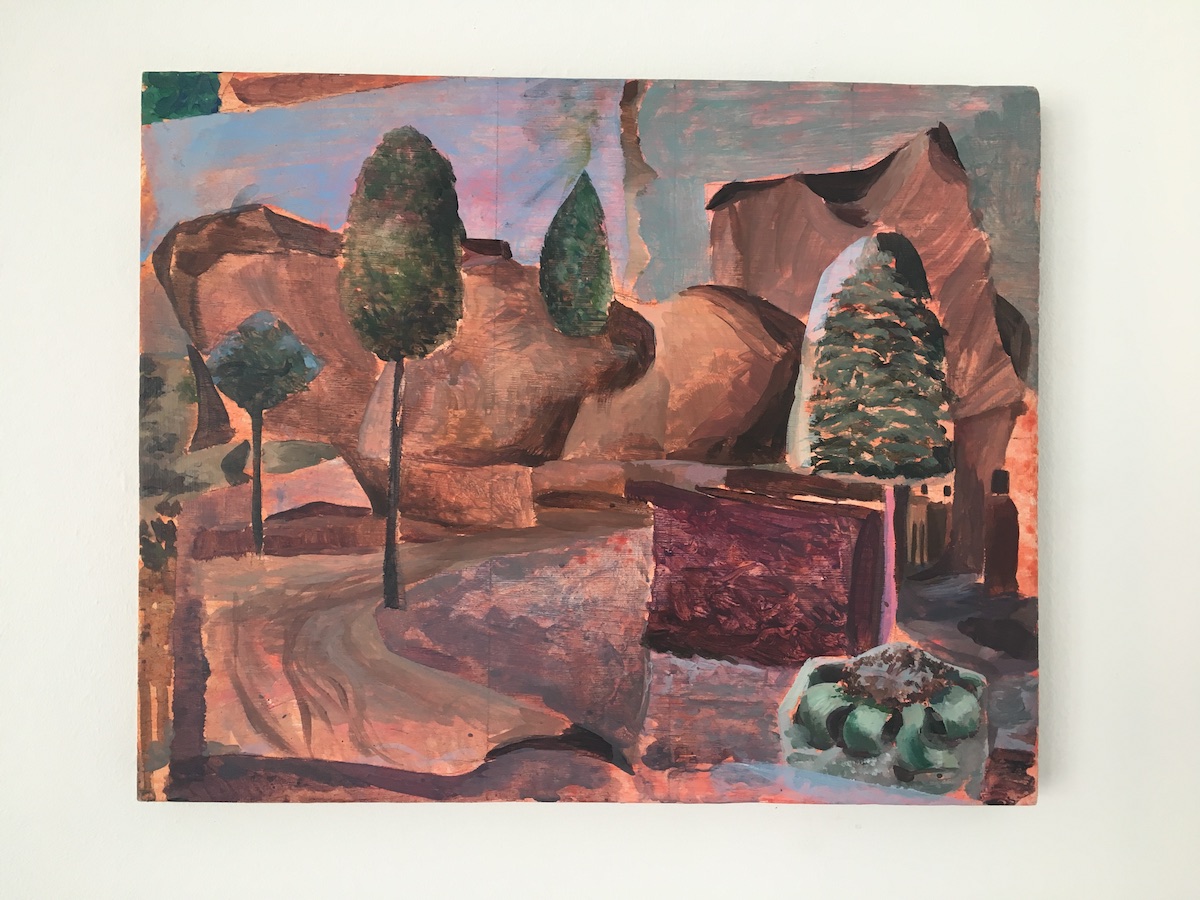

Heralding this trained eclecticism were Grotto and Mistake Painting, paired at the visitor’s immediate left upon entering. The trough-like recesses of two salmon-pink grottos are rough-hewn as the other shavings of this collage-on-a-brown-hardback. Earths and azures are a jumbled regurgitation of an iconography. To look at it alone is to be fixed on a potent composition while adrift in craggy ether – an embodied tension which was compounded by its neighbour. Mistake Painting is a tiny brick wall of sponges whose industrial colours recall emblazoned, luridly tropical beach towels. Each one is studio dross, deliberatively stained. They are gorgeously to hand and insultingly distant, tokens of an unobtainable place.

No theme, moral or narrative, punctuated. Pastoral, people-less scenes of earth, meteor showers of art supplies jaggedly asunder; deserted bathing or picnicking spots; these illustrated only the striking sufficiency of the medium in each instance, its nexus of reference. Holiday is a flocculent slab of plaster, dirtily inscribed with a parasol and barbeque that looks more like a gryphon-sized megaphone blasting obscure meat – always a beach irritant. It is tempting to relate work like this to ideas of excess, withdrawal and play. However, ultimately what preponderated was the performance – tangible, corporeal – of practice, a practice of making or possibly painting, a strained three-legged dash of artist and baggage – technical, critical and material. Here the artist was conscripted and bundled under. Some self lingered functionally, the hypothesised glitch at the root of these passions of method. This practice is vagrant and reflexive. It rifles erratically through the conditions which nest the evasiveness or self-effacement of its steward. Such action was glimpsed in 30 Minutes, a 360 x 220 cm triptych of cardboard with that damp and trudged-upon look of salvaged refuse. It leaned rakishly in its ground of pale rose, boasting its porn-ishly sketched Arcady of bull, drum and fronds, etc. It humorously conveyed the essence of this practice, not least with its individual redundancy.

The technical efficiency and physical capacity of this practice, foregrounded as medium, endows the work with vaulting, cavernous reach and scale. There is the compelling command of heft, welters and walls, piled, sundered, dispelled at will. One’s embodied remoteness resounds in an inherent tease and frustration of desire for sustenance – moral or intellectual – futilely traced in barren, abstracted forms. Being with the work can feel bracingly lonely. This exclusion echoes a faint formal pathos – cold acid hues like The Cure’s Boys Don’t Cry; desertion under vindictive Baroque skies – almost warranting the supposition of an organising principle in the form of a psychological portrait of the artist. I found the remnants of once-squelched-in plaster most emotive. Untitled (Rock) is a vertical, bean-shaped pat of brittle, aqua sky framed with a grey incline. A Sisyphean worm trails a tumbling marble of smouldering plum. However, the relationality of these tropes – to studio processes, institutional art references, each object and facet to every other – is unbreachable. Ostensible narratives confirm the imperviousness of this practice to the probing of empathy and interpretation beyond the technical and aesthetic.

This is brutal and unexpected – suggestive of dysfunctionality – for one is subjected to many mannered vistas, canopies and outcrops, from which nature normally makes overtures. In several untitled landscapes, such scenes are subjected to coolly perpetrated dismemberment, their knowing undergrounds of flaring sienna exposed like flesh. The art history is desultory, the furniture crazy. Redmond confirmed in chatting that an apparent concern with reality and culture is present by default, an inheritance from his previous realist figurative work and ongoing fascination with National Geographic. The didactic, youthful ambience of the provincial sanctuary he was inserted into with the Paul Funge Residency, is an intriguing background for his phase of voracious, sceptical reappraisal. Reality is recurrently abject, denuded in process like driftwood inviting decorative use. But in this maelstrom of otherwise aesthetic networking, these ideal fossils engender a constructive alloy. In a gravel or sediment expended in confluence, culture per se remembers the breadth and contingency of its dimensions.

Redmond’s thoughtful handling of telling, restricted materials – canvas, wood, paint, plaster, etc. – impels our thinking in the familiar directions of painting’s future, history and contemporaneity. A salient theme is the ambition of artists who paint, to challenge, or at least complicate, the physical discreteness of their work(s), and/or a supposed artistic ‘autonomy’ of those discrete things. The insoluble-looking puzzle for formalist abstractionists in particular, is that of breathing new life into old hat they are loathe to shed. A common tactic is to contain paintings within a framing practice, setting up a confrontation between paintings and e.g. spaces of ‘installation’, and their respective modes of engagement. A more fanciful but tantalising prospect is the ‘opening’ of the work – while preserving some ‘spirit’ of compositional rigour – to the unforeseeable qualities of its environment, including the contributions of the viewer orienting their senses in an ‘immersive’ situation of free interaction. However, taken as an example of painting’s ‘expansion’, Redmond’s work is interestingly aberrant – and backward-looking – devoted as it is to capturing and revealing the conditions and threads of its formal intelligence with impartial, rapacious fondness. In the context of the work’s installation, a threshold is reached from which its practice appears integrally, not as an array of curios. Its prodigious, indefinite content is rivetingly offsite, a gift of frustration with immersive dimensions. The viewer espies a field of wanton exchange at a tangibly unbridgeable distance, and physically negotiating the bounds of its sterile site of discovery, explores the fluctuating contours of this tension.