“The technical importance of the scientist is bound to give him the independent administration of large funds and end the mendicant state in which he exists at present. Scientific corporations might well become almost independent states and be enabled to undertake their largest experiments without consulting the outside world — a world which would be less and less able to judge what the experiments were about.” (J.D. Bernal, The World, the Flesh and the Devil: An Enquiry into the Future of the Three Enemies of the Rational Soul, 1929.)

“Recently, machines have gained automatic self-reproduction […]. Today, machines dominate the scene. In our experience, they have already managed to substitute nature. The rhythm of the machines is the rhythm of our lives.” (Vilém Flusser, History of the Devil, 1965)

From November 1981 to November 2009 Circa released 130 issues in print. Although the magazine persisted through various virtual afterlives following this — firstly as a series of PDFs that served as digital surrogates for the physical artefact, then later as a more traditional website publishing reviews and texts on contemporary art in Ireland — it is that original print run which is the focus of this editorial project.

‘an_archaeology_of_the_future’ steals its title from a phrase in Julian Stallabrass’ Internet Art: The Online Clash of Culture and Commerce (2003):

Net art, then, is seen as an archaeology of the future, drawing on the past (especially of modernism), and producing a complex interaction of unrealised past potential and Utopian futures in a synthesis that is close to the ideal of Walter Benjamin.1

Later, this passage would be used as the epigraph in the introduction to the Dieter Daniels and Gunther Reisinger edited anthology Net Pioneers 1.0: Contextualizing Early Net-Based Art (2009). The phrase an archaeology of the future carries an inherent paradox. Archaeology, a discipline typically dedicated to digging out old things, now finds itself oriented towards a future whose materiality remains always contingent. Winding its connective current around this pair of examples, the concept suggests that (re)turning to forgotten, technologically-infused relics, may help us in anticipating what comes next. What alternative futures, modifications of our own present and its current trajectory onwards, can possibly be uncovered by revisiting ideas that were previously overlooked? In the case of these publications there is also a desire to shine a light on an area of the artworld which has, historically, found itself too often ignored. That is, the endless, and frequently problematic, relationship between art and technology (especially in its industrial and then computational variants).

In 2012, just three years after the final physical edition of Circa, Artforum celebrated its 50th anniversary. This occasion was accompanied by the publication of a special double-issue that printed, alongside the usual suite of features, articles, and reviews, reflections from writers on some of the most important essays that had appeared in the magazine over the course of its storied-history. Of these, one of the most notable was Claire Bishop’s ‘Digital Divide: Contemporary Art and New Media’. The text, by the always polemical art historian, opened with the rather blunt, and puzzling, question: ‘[w]hatever happened to digital art?’.2 Bishop pointed to the exponential growth of technology in the first decade of the 21st century and our increasing entanglement within its systems, as being one of the most significant developments of that present moment. In spite of this, Bishop lamented that contemporary art, as a whole, had been “curiously unresponsive” to the topic of digitality.

That such a blindspot existed, or could be identified by Bishop, had much to do with that fact that the essay founded itself on a discrete separation between the worlds of contemporary art proper and new media art. Whilst noting that the latter had its own long history of exploring technology’s role in society, the category was roundly dismissed in the introduction as “a specialised field of its own”. It is this separation, amounting to new media art’s sundering from the originary (dominant) category of the mainstream artworld, which shaped the very premise of ‘Digital Divide’. Herein, the contributions of countless practices were effectively excluded, by reinforcing this notion that new media art existed outside of mainstream artistic discourse. Unsurprisingly, this brash ignorance of an entire (sub-)domain of art triggered a cauldron of boiling responses from various critics, historians, curators, and artists associated with new media art. In the following issue of Artforum, curator Lauren Cornell and critic Brian Droitcour penned a rebuttal that, whilst acknowledging the traditional artworld’s historic reluctance to embrace (new) media technologies, proposed that Bishop’s particular point-of-view was woefully outdated.3

Bishop’s essay, despite provoking criticism, was an old and embedded narrative. One which exemplified the ways in which, for much of the 20th and early 21st century, the artworld often resisted and overlooked a deep engagement with the concept of technology. This was not a new concern. In 1980, a year before the foundation of Circa, the American art critic Jack Burnham published an essay which announced that the relationship between art and technology had become “the panacea that failed”.4 This critique was all the more striking as Burnham had built a reputation, through the late 1960s and early 70s, as a celebrated proponent of the nascent art and technology movement. His theory of “system esthetics” advocated for processes (systems, networks, interconnectivity) over things (static objects), with his writing emerging at a time when the artworld’s established order appeared to be courting the domain of advanced technology.

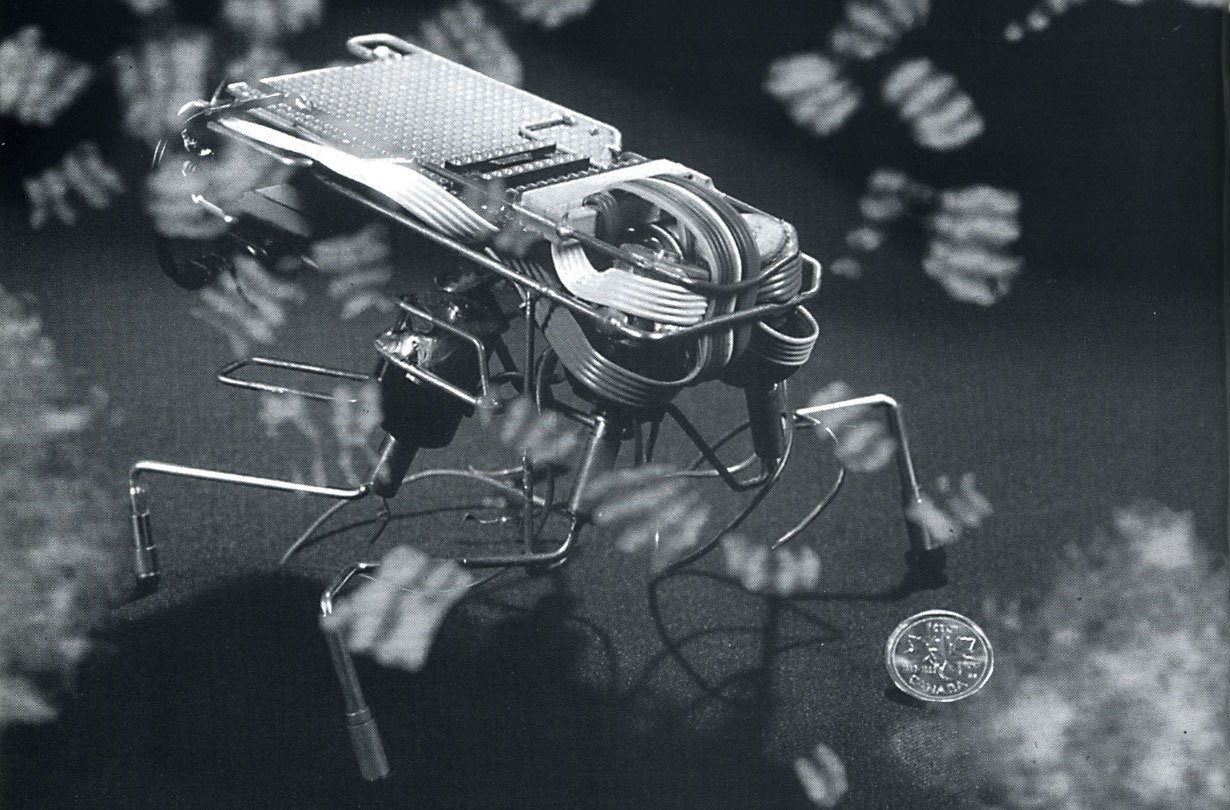

Projects like the Experiments with Art and Technology (E.A.T.) (established 1967), brought together artists, most famously the likes of Robert Rauschenberg and John Cage, with a team of engineers, in order to explore productive collaborations between both fields. This period also witnessed a slew of high profile exhibitions located at the intersection of art and technology. The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age was launched at New York’s MoMA in 1968. That same year, the Jasia Reichardt curated Cybernetic Serendipity: The Computer and the Arts was hosted at the ICA in London (later travelling to Washington D.C. and San Francisco), showcasing a wide array of early experiments with computer graphics, music, and robotic sculpture. Burnham’s own Software – Information Technology: Its New Meaning for Art took place at Brooklyn’s Jewish Museum in 1970. This was something of a culmination of his aesthetic theory with the exhibition presenting works from both artists (with an interest in technology) and engineers (with artistic inclinations), and marked a blossoming peak in that era’s enthusiasm for such collaborations.

Yet, a decade later Burnham declared the relationship had effectively run aground. The once-vaunted champion of an integrated system of art propelled forward by technological advancement, now opined that many of the attempts by the artworld to utilise new forms of “technical gadgetry” (and even with the assistance from renowned artists like “Rauschenberg, Oldenburg, Warhol, Kaprow, Lichtenstein, Morris, and Smith”) had resulted in work that ranged from “mediocre to disastrous”. Shows such as Cybernetic Serendipity and Software had been plagued by a constellation of technical difficulties, with many of the works of art malfunctioning during the exhibition runs. Beyond the schism wrought by these formal and practical problems, the broader political climate had contributed to a growing skepticism of art and technology. The spectre of the Vietnam War, as well as Cold War-era anxieties over the threat of human annihilation, loomed large, casting a shadow over technological progress. As a result, the reputation of much technological art was poisoned by association with the military-industrial complex.

These separate episodes, Burnham in 1980 and Bishop in 2012, bookend the print run of Circa, and help to somewhat contextualise the critical imperative of this editorial project. In 2025, the exclusion of new media technologies from the world of contemporary art is very much an out-of-date narrative. In one sense, the dissolution of the divide is straight forward: we’re all digital natives now. (Attempting to type out the myriad of instances that point to the accelerating encroachment of digital technologies, networks, and systems into everyday life feels utterly redundant, so familiar as we all are with these processes.) Thus, it is no surprise that over the past number of years the artworld has seemed more receptive to the topic, and materiality, of technology — with the sub-category of new media art now comfortably integrated within the larger body of contemporary art. Within an Irish context, we need only consider artists such as Alan Butler, Bassam Al-Sabah, Doireann O’Malley, and John Gerrard (who performed a review of IMMA’s website in the 88th edition of Circa in 1999), for examples of work which would seem to effortlessly blur the lines between these, previously separate, institutional categories.

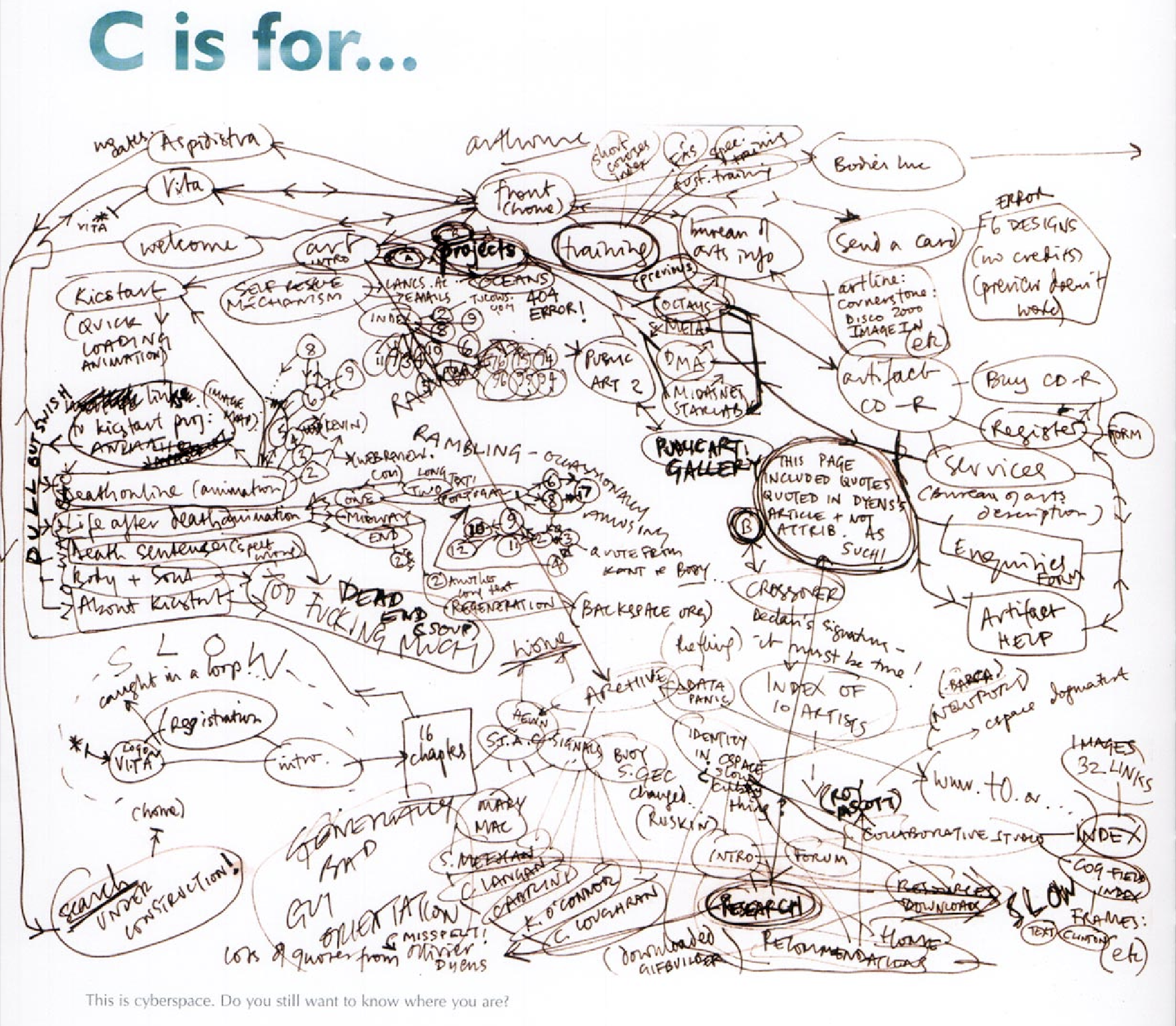

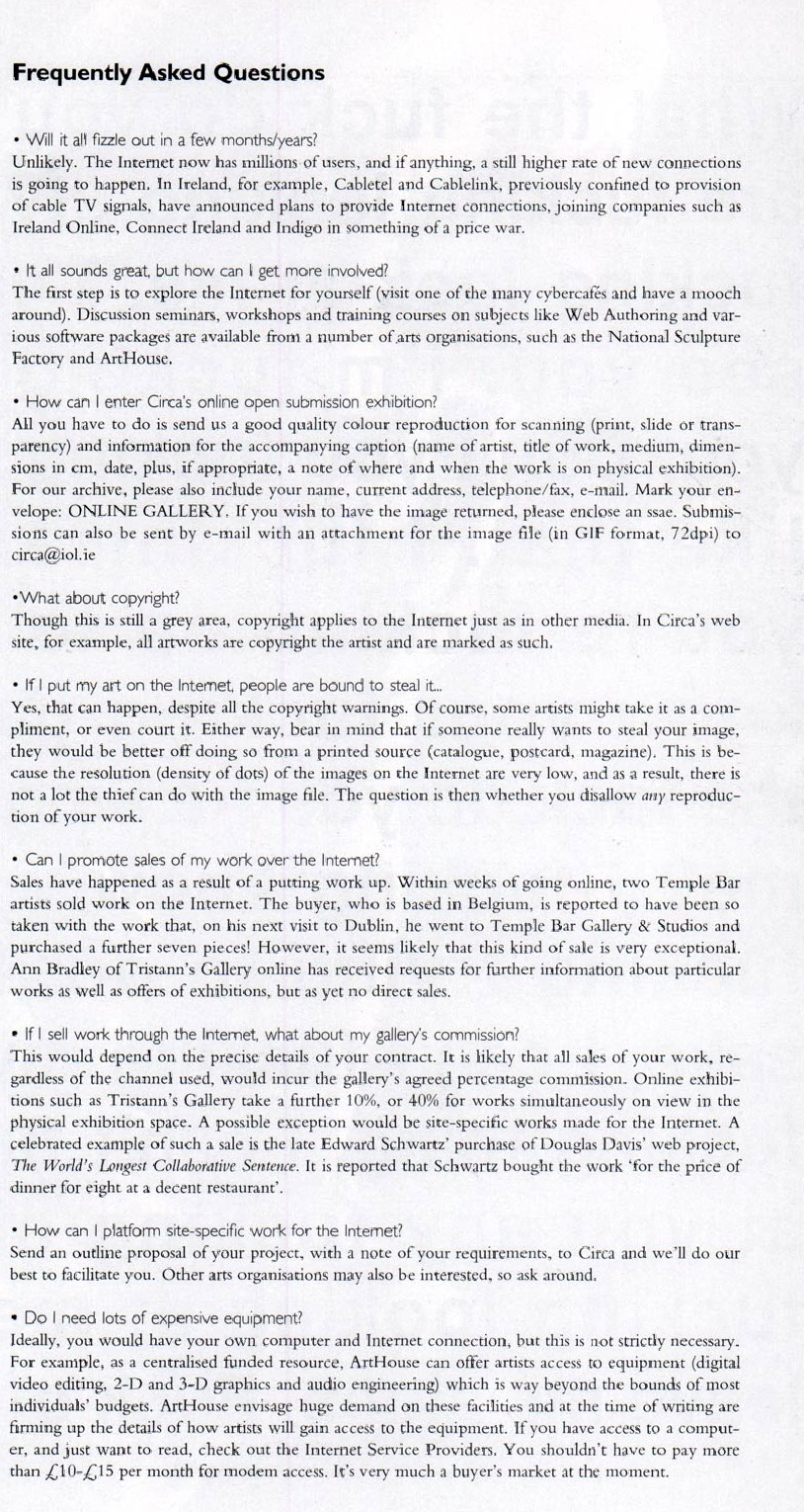

Even so, the lessons from Burnham and Bishop are instructive as they frame a particular moment in time. Accordingly, when we trace Circa’s archive — despite the fact that its timeline aligns with the global movement towards our current post-digital society — the presence of artistic collaborations with advanced technology seems somewhat subdued; although, not entirely absent. Within these pages there are infrequent outbursts of machinic uprising: a review of Artists/Computers/Art (a show on “computer graphics created by technologists”) from Brian J. Kennedy appears in 1983; in 1995 Ivan Pope explores the possibilities of the new-fangled world wide web as a creative platform for artists; Gemma Tipton ponders on the digital collector in 2004. From 1998 to 2005, Michael Cunningham ran an almost consistent feature entitled ‘Slave to the Machine’. And in 1999, the magazine commissioned and published a special supplement on ‘Art + Technology’, which was edited by new media artist and theorist Eduardo Kac.

These sporadic irruptions signal occasions of connection, which this project seeks to pursue and revisit within the context of our own contemporary moment. As an editorial platform, ‘an_archaeology_of_the_future’ turns to Circa’s vast archive, the most robust and accessible map of art and criticism on this island from 1980 onwards, in order to unravel the knot of our developing relationship with technological systems. This occurs in an environment wherein rapid advancements in technology, now particularly in regards to artificial intelligence, present a scenario wherein our present-future may find itself undergoing a radical restructure. Pursuing cutting-edge technologies has, historically, always relied on massive institutional and government backing, and so whilst breakthroughs in A.I. may provide gleeful possibilities, the dark side of that coin (to touch on concerns suggested by Irish scientist J. D. Bernal in the epigraph) lies in who is constructing these technologies, and for what ends.

The commissioned texts making up this project hope to offer responses and ruminations, drawing influence, either explicitly or more abstractly, from the disjointed and partial compulsions in the Circa archive which dwell on the question of technology. These historical fragments — sometimes tinged with optimistic curiosity, other times skepticism — offer up an opportunity to (re-)examine how artistic and critical engagements with technology have evolved. Here, the archeological tendency to look back is performed with the future very much in the mind’s eye. In a world increasingly shaped and over-run by automation and algorithmic control, it becomes evermore important, and pressing, to critically engage our relationship with advanced technological systems. The intention here is not to offer up any kind of singular theoretical position, or one clear line of a minor history (a fabled counter-history to art canonical decree), but rather to act as a series of interventions which push our understandings of art and technology, its past and future, into a forceful dialogue.