Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian: Sunset,Sunrise

Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, 10 August – 25 November 2018

When a life and career has stretched throughout over two thirds of one century and continued into the next, it is difficult not to regard a retrospective as a kind of funeral, a wrapping up of intent, a final statement. One can feel at such shows as though work is being boxed up and consigned to the time in which it was created, with no eye to the future.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian is 95 now, but Sunrise, Sunset, her extraordinary exhibition at IMMA, has no feeling of ending. Both the works shown and the artist herself inspire a sense of ‘ongoingness’ and expansion. Like a number of older artists, she has been rediscovered at this late stage; nominated for the V&A Jameel Award in 2011, her first solo American exhibition in 2015, and Iran’s first museum dedicated to a woman’s work opened in her name last year.

There is a joy and liveliness in the exhibition at the Irish Museum of Modern Art which makes you feel glad that her grand age has allowed her to live long enough to be acknowledged as she now is, in a way that few women artists are before, or even after, their deaths. This is a celebratory, not a commemorative, space.

The artist was born in 1924 in Iran, to a family of well-to-do merchants. When her father, a designer in his spare time, was elected to parliament, the family moved from Qazvin to Tehran where she studied drawing at the Fine Arts College of Tehran. By the time Monir was interested in travelling further afield, World War 2 had begun and Paris out of bounds. She travelled instead to New York, the site of germination for her sprawling career, and where she would live for twelve years.

A 2016 film made by Bahman Kiarostami named Monir shows as part of the exhibition, a result of two and a half years spent together. It introduces us to the forceful, warm person behind the work, and a life marked by upheaval and regeneration. Studying at Parsons School of Design, Monir mingled with cultural figures on the brink of becoming icons: William de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Andy Warhol; she was described once by John Cage as “that beautiful Persian girl”. In 1957 she returned to Iran. Travelling and studying native art, she gathered the interests and techniques which would go on to characterise her career. Before she would be forced to leave Iran as a result of the Islamic Revolution in 1979, a pivotal moment came. In Shiraz with American artist friends, she saw the Shah Cheragh, a mosque with a domed hall covered in hexagonal mirrors. The space was rendered a spectacular flare of multi-prismed light which overwhelmed her. “It was a universe unto itself, architecture transformed into performance, all movement and fluid light, all solids fractured and dissolved in brilliance in space, in prayer.” she describes in her memoir.

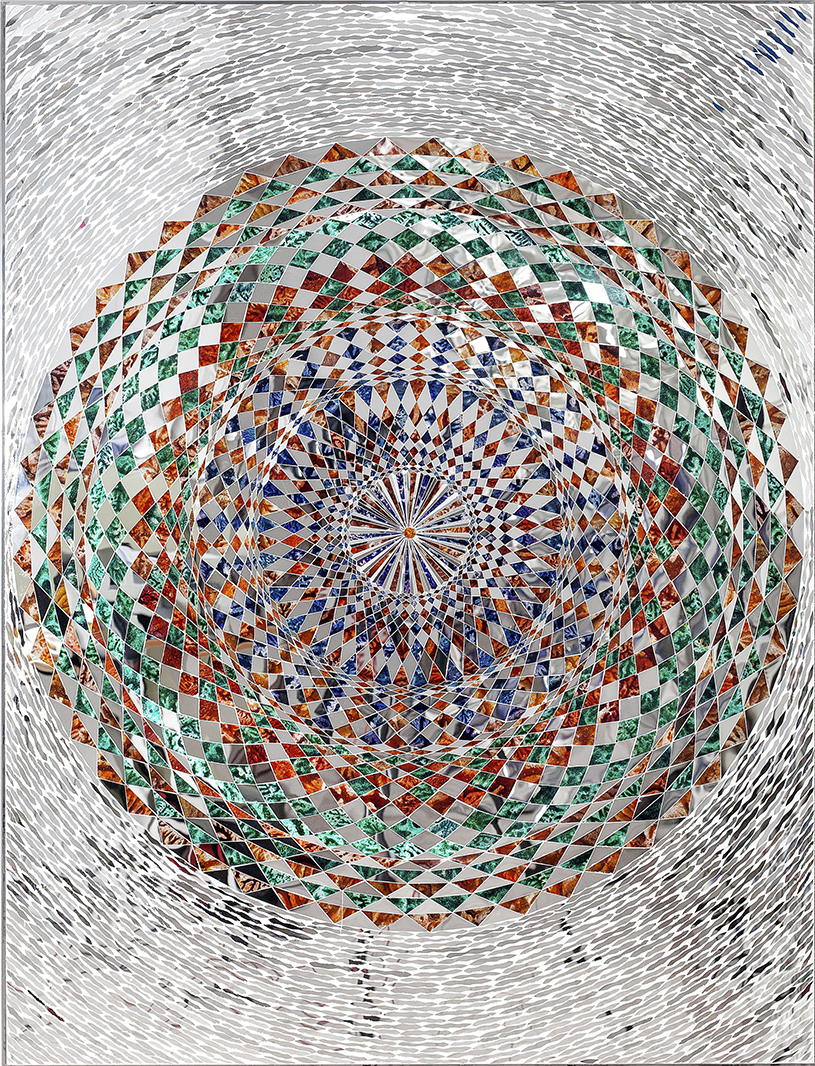

In the last decade, Monir’s career has had a renaissance, with her first US solo museum exhibition at the Guggenheim in New York in 2015. Last year, in what must have been a satisfying turn of events for a former exile, Iran opened its first museum dedicated to a solo female artist in her honour. This IMMA retrospective, the first time her work has ever been shown in Ireland, is a comprehensive overview of her oeuvre which has commonly included mirror mosaics, abstract monotypes and reverse glass paintings, inspired by geometric patterns which recur in traditional Iranian architecture and mosques. More than seventy works of varied media are on display, but geometry is the lynch-pin, the constant which unifies most of her work.

By its nature, the repetition of all this geometry can be dulling, especially in a comprehensive (comprehensive to the point of exhaustion at times) retrospective such as this. But the awe and grandeur of the more spectacular work like the dazzling Sunrise, a 2015 mirror and reverse-glass painting, snaps me out of that, and so too does the intimacy of the included drawings and collage.

A porosity of borders of all kinds characterises this show, the fluidity of decades and influences and cities, of formalities and technique. I can’t help but feel mournful for a different time in which such relationships seemed destined to go on growing and amalgamating and becoming. The work on show here is a perfect argument for such fluidity, a marriage of ancient craft and technique from Monir’s native Iran and the abstraction of the Western art world she moved within at a pivotal moment in her life.

I don’t mean to paint the post-war twentieth century as a utopia- and indeed it was due to Monir’s position of class privilege that she was able to move with the freedom she did- but certainly there existed once, more of a sense that movement was not only possible but desirable, that belonging to more than one culture was not suspect but to be encouraged, and that someone able to do so, as Monir was, might create great things.

The tension of a life lived in more than one place draws me in: the atavistic, the feeding of one life lived into the all, the other imagined ones you necessarily must abandon. Reckoning with a home you have left, and finding that a place you will never be wholly of again is still capable of changing you, and changing the course of your life.

The secularity of wonder and ecstasy and transcendence which Monir expresses so often in her work is of special interest to me, too. Some large part of her life was determined by religion, through the disruption wrought by the revolution. She has spoken critically of Iran’s government and of Islam, telling the Guardian: “Iran was a beautiful country before the revolution…The people are very much for progress – not these stupid Islamic things.” In Shiraz, she says, her pivotal experience in the mosque in 1971 “…was so beautiful, so magnificent. I was crying like a baby”. But the experience of wonder and spirituality which finds expression in her art was not founded in a religious conversion. It’s a question that obsesses me, a lapsed half-Catholic, still nursing a mish mash of anger, disdain, and angst for my missing faith. Where do we go after God? How do we chase wonder when we no longer believe, or never did? In my life I’ve gone from earnest believer, to mocking cynic, and now to something much more muddied and ambivalent.

Is it possible to resist the trappings of the Church which have caused so much unnecessary pain and misery, while still acknowledging its power- aesthetic and otherwise- over you? I think of Monir’s disco balls- one gifted to Warhol which sat on his desk- a perfect emblem of 70’s fun and excess, made with the traditional mirroring methods of her country. I think too of how I and so many others repurposed Catholic iconography as an experiment with repudiating it, of queer culture and the dazzling, gaudy Virgin Mary, of wanting to own the little glow in the dark Jesus but not quite knowing why.

Individual works are capable of silencing and winding and astonishing you. For me it was the Group 9 (Convertible Series) mirror and reverse glass painting which stopped me, drawn into it and its miraculous surrounding light. But it’s more the effect of seeing all of it here together, years tumbling after years, as chaotic and singular as a life itself. It’s beautiful to see the work of a woman’s whole life in one place. It’s overwhelming, sometimes exhausting, boring perhaps, and yet often it’s glorious. The work is evidently a result of access to quiet and deep space. In those darker rooms, you get lost in all the time, all that light being created in the dark. In the quiet of that dark, and all that history- you get the feeling that what is built in spaces like this really could be anything at all. Part of this is simply that she has happened to live so long; part of it is the way in which she has lived- expansively.