Susan MacWilliam, Modern Experiments at the Butler Gallery

Allow the light to come into your eyes to better understand what is before you instead of casting outward your gaze to capture what you think is there…

A different manner of looking is required if we are to see anew. Let us close our eyes for a moment and try not to focus on any one thing in detail upon their reopening. As we keep our gaze softly focused, we allow light into our eyes by way of our auxiliary rod cells rather than that of our oft-overused cones, which merely reflect definition and never that which is beyond. In order to see anything out of the ordinary, we must learn to look again with unexpecting eyes.

Look. An otherwise undetectable gas glows yellow-gold from within glass tubes, sealed in formation and charged with electricity. An Answer is Expected (2013) is a statement piece by MacWilliam designed to interrupt the usual neural-pathways that govern habitually our general depth of perception.

Conspicuous consumption of customary confrontational ‘neon’ signs aside; next up, we have a conflation in terms. On screen: the artist as medium. If truth be told, it is a double act of conflation which possesses MacWilliam as she performs silently and without colour the role of medium on screen. The artist sits tied hand and foot to a chair regurgitating [as] The Last Person (1998) tried and prosecuted in 1944 under the British Witchcraft Act of 1735.

Another sign. White neon lettering hangs on a white wall and asks: Where are the dead? (2013). An obscure question not least for the camera lens howsoever you take it. MacWilliam, it seems, Faint [s] (1999) again and again at the thought: nineteen times nineteen screens of varying dimensions staged on level ground, set amongst snaking cables charged with the perpetual fainting of purple dress while bird song fills the ears.

What lies beneath sight is vision. A self same named mystical man turned 1940s variety show lights up Kuda Bux – the installation (2003) with as many as one hundred electric light bulbs. The scene is set for seeing through closed eyes – blindfolded in fact for empirical exigencies. The blind-sighted antics of Kuda Bux (1905-1981) repeat on screen from behind the perfect frame of a 1950s television set. Amongst other such prop-paraphernalia: a 1930s armchair from which to watch all the commotion.

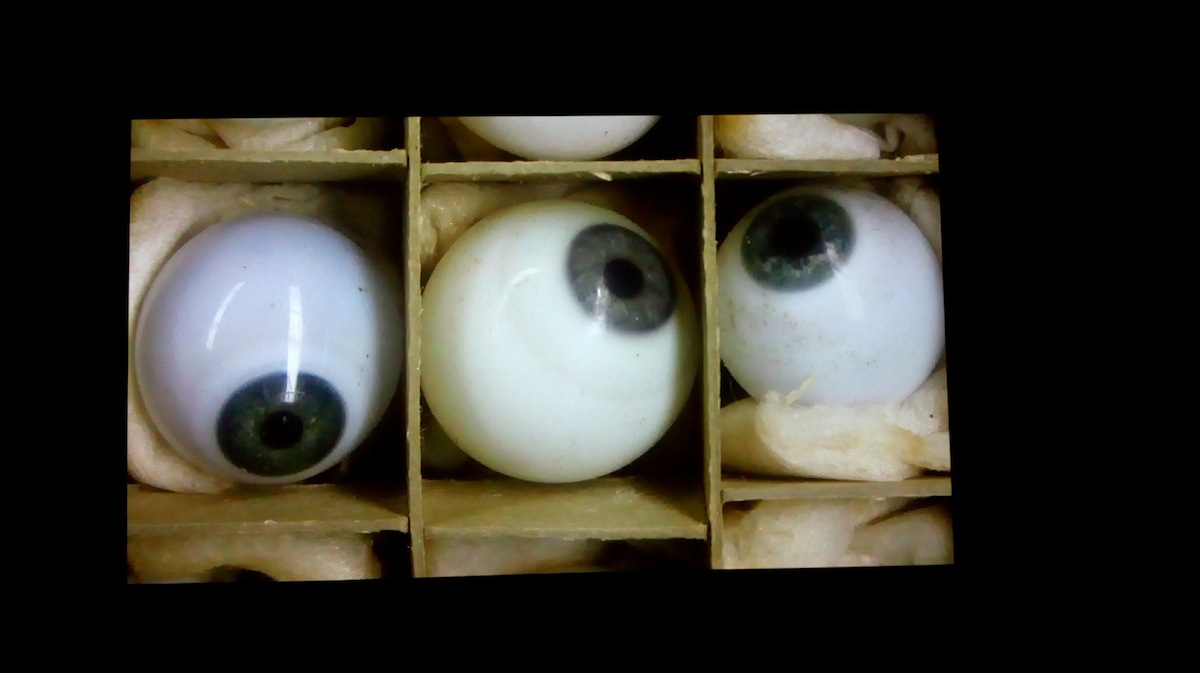

Every which way the eye wanders, a host of parapsychology personalities permeate the landscape of psychic ephemera. Numerous stereoscopes invite both eyes to peer into situations of para-personality or para-para-phernalia, some even recall imagery already used within this show-and-tell survey exhibition, reflecting a circumambulation of sorts.

MacWilliam does stand out the most, however, amid the most notable of parapsychology luminaries. Throughout Modern Experiments, the subject of the artist is felt as external to that of the material. This, I feel, is partly due to the fact that MacWilliam seems to leave aside the role of artist for that of ‘acting’ researcher.

Modern Experiments presents itself as an open invitation for us to enter in, into an inner circle of sorts, but the exhibition as a whole keeps its audience at a distance and does not encourage that shift in focus necessary for the expansion of our perceptual embrace; that softening of our gaze. Instead, I feel, we take an archival trip down a MacWilliam memory lane, circumscribing the subject matter rather than opening it up to subjective response.