Susan Thomson: Grace Quilligan and Zsofi Abel

Monsters have always defined the limits of community in Western imaginations… Cyborg unities are monstrous and illegitimate; in our present political climate we could hardly hope for more potent myths for resisting and recoupling.

– Donna Haraway A Cyborg Manifesto

Biocodes (language, ways of dressing, hormones, prostheses) that once belonged to feminine, masculine, heterosexual, homosexual, transsexual, or even genderqueer configurations can achieve means of expression that are denaturalized and offbeat and free of a sexual identity or a precise biopolitical subjectivity.

– Paul B. Preciado Testo Junkie

A man returns home, uninvited, for his brother’s engagement. The character, Ambrose Mordrake, has a small face on the back of his neck, a face that seems to compel him to do things he wouldn’t otherwise do, and which begins to speak to him in increasingly menacing terms. The film is based on the story of Edward Mordrake (a feature film about his life is in development, coincidentally), an apocryphal man of the Victorian era possessed of two faces, a small female one on the back of his head which portrayed the opposite emotion to his male face. The short film I am not a Monster at the National Film School, IADT, directed by Grace Quilligan, begins in a slightly stilted manner but soon warms up, and becomes utterly compelling. Ambrose is shunned and derided by his family: The bandaging of his other face, his covering it with a hood, followed by attempts to simply wear it proudly, are met with cruelty, and the film ends in a violent act. The film owes something to David Lynch, particularly Eraserhead (1977), the face appearing as a prosthetic kitsch kind of horror. There are shades too of American Psycho (2000) as we wonder what is ‘real’ and what is internal to the character. The fast cut editing, strobe and wide-angle close-ups, reflections in mirrors, as well as effective sound design, featuring whispering voices which mutate into a single voice from the face, create a claustrophobic and menacing effect. Although the director mentions deformity and mental illness, specifically paranoid schizophrenia, in her notes, this is not a realist portrayal of a specific physical or mental condition (craniofacial duplication does exist but the survival rate is a matter of months, and in schizophrenia the violence committed is very unlikely so this could add to misconceptions). There is the risk of playing into familiar, non-progressive cinematic physical and mental tropes, and for me the film works best read as a polyvalent literary fiction, a Doppelgänger narrative, an allegory of shame or outsiderhood, along the lines of Dostoevsky’s The Double, Kafka’s Metamorphosis, or even Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray. In addition, in Roman mythology, Janus, is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, looking both back into the past and forward into the future, and is sometimes the harbinger of War. Ambrose can therefore be read as daemonic, a god-like or ghostly figure, come to celebrate the ritual transition of the impending marriage, which has in a sense conjured him up for that purpose.

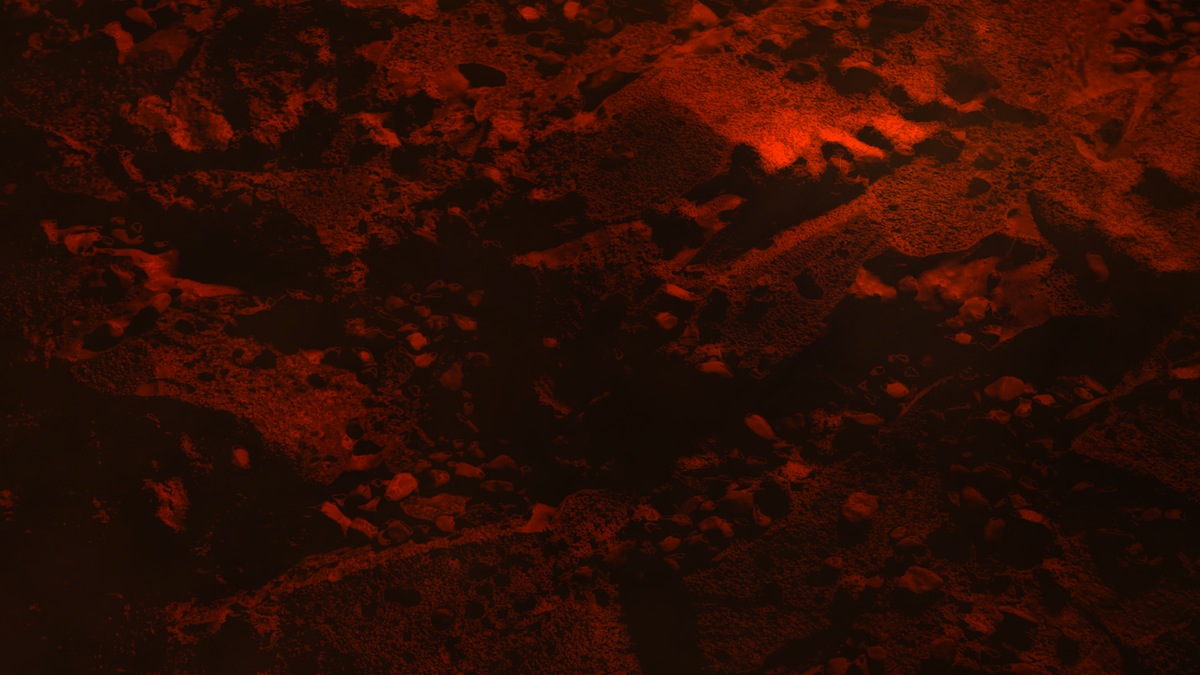

While many films tends to ground themselves in narrative, though the symbolic meaning may remain elusive, moving image work typically keeps narrative itself more open and polyvalent: strange weather, a moving image work by Zsofi Abel in the B.A. in Fine Art show, is a case in point. We are presented again with haunting sound design, and here a sci-fi narrative. Following a dark, cloudy night sky, the camera cuts between several CCTV-style, glitschy images of a smoking, half-built abandoned building, and trash – lightbulbs, plastic bottles, CDs, paper – as if a gendernaut, a Martian or cyborg scientist is scanning images of a destroyed earth. The camera glides around a green 3D hexagonal building or spacecraft, and the construction appears to revolve, as if in zero-gravity. Now the androgynous scientist is in a retro lab, filing away strange insects that have grown, moths, or are they inky bits of crumpled paper? We never find out who this character is, dressed in a white and silver space suit, a silver band of makeup across her eyes, and one blue eye, which whirrs in a computerized circle, perhaps a bionic eye which has captured those black and white images. As this eye seems to connect up with the smart board, an alarm sounds and she exits the lab, reappearing as a cut-out, an outline on a red, rocky planet with plumes of smoke, which is either an Earth now uninhabitable, post-nuclear or post- climate catastrophe, or it is her arrival on a new planet, Mars, with all of its utopian potential. This is an homage to Ziggy Stardust, genetically spliced with a climate change manifesto, or Paul B. Preciado’s post- gender Testo Junkie and French TV production Missions (2017), regenerating and cross- pollinating on their journey to Mars. The only danger is that with the increasing on-screen presence in cinema of the ‘female-embodied robot’, some of the deconstructive feminist potential inherent in Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto, continuing in Susan Stryker’s ‘somatechnics’ (where technology, power, and the body are inextricably linked), has been appropriated by the mainstream, or indeed is already being used in sometimes reactionary ways. However, it could also be said that #MeToo and #TimesUp are in a sense cyborg movements.

IADT is in the relatively unique position of containing both a film school and an art school. With these works, there is a commonality which reflects recent developments in Ireland and in the wider world. It is fitting that these films foreground the body as problematic, unruly, not fitting in neatly, but instead potentially double in nature, deviant, part-machine, queer, even monstrous. I found both of these works genuinely inspiring, and there is much else to like in the degree show; the ambition and professionalism of the National Film School in the departments of animation, film and model making, as well as other strong works in the art school. Given how porous are the boundaries now between moving image art and film it would be interesting to see greater collaboration between the Film School and art departments, as well as between students in the form of collectives. This could mean perhaps greater access to and training in film production equipment for art students and more conceptual or experimental thinking within the Film School, rather than the emphasis on the conventional or commercial, and I hope to see such transdisciplinary work in future graduate shows.