Laurence Counihan: Muireann Kelleher

Muireann Kelleher’s Labour of the Months

The space is dominated by reams of paper adorned with abstract markings which lead towards stalled machinery in the form of a rusted four-legged unit, outfitted with a deactivated side-fan and cage on top. From the latter, a number of pens appear dangling via thread in hydra formation, stilly poised over the paper as if in a state of suspended animation. Turning towards and engaging the set of headphones on the adjacent wall we are informed by voice-over that this scene that greets us is in fact the remnants of a strange type of hybrid performance, one which has been constructed by a collaboration between human-artist and automated machine driven processes.

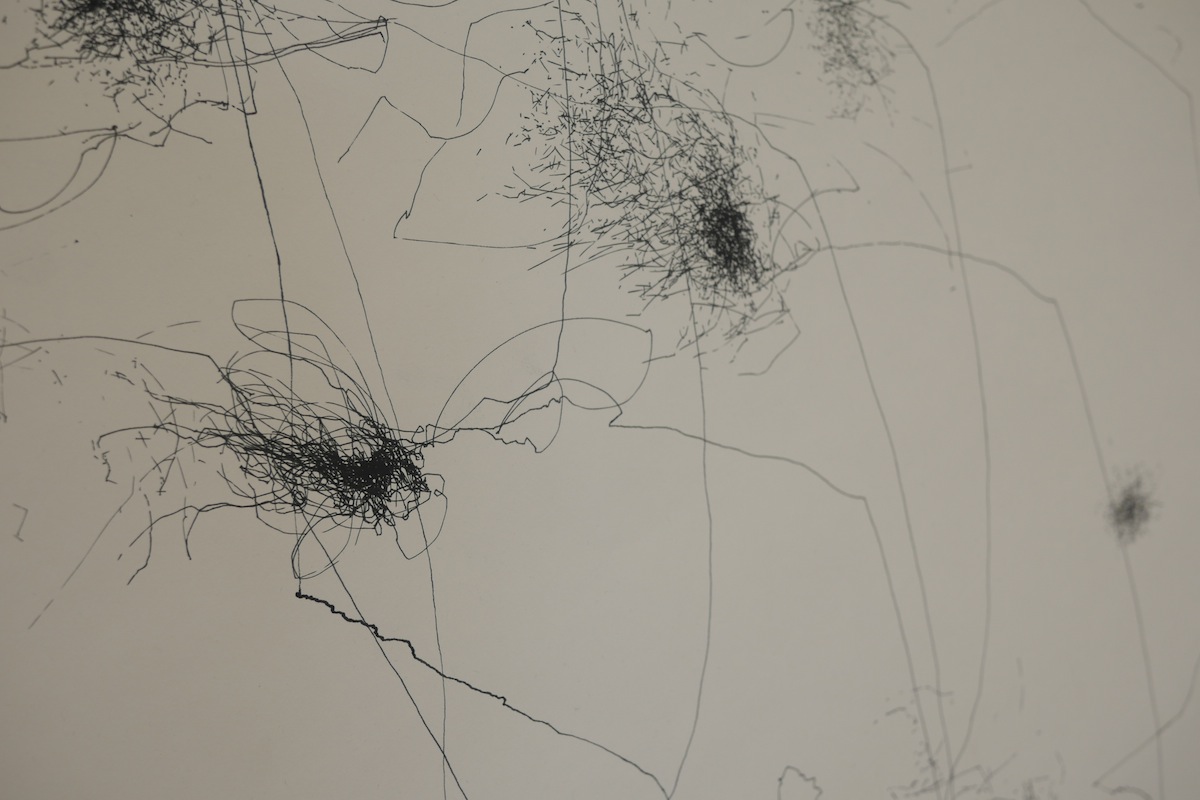

The piece takes as its initiation point the historical term ‘the labour of the months,’ which refers to illustrations from Medieval and early Renaissance art that depicted various types of labours, or duties, each of which was associated with a particular sign of the Zodiac calendar. Employing this concept of cyclical systems, Muireann Kelleher’s The Labour of the Months has been developed through a series of precise automated processes, repeated numerous times leading to the construction of the final artwork. All of the markings on paper are the result of a surreal dance of pens, wherein movement was instigated, and subsequently sustained, from the air generated by the now dormant fan. A monitor on the wall gives us a top-down view of this performance in action. Viewed through the bars of the cage, the tightly cloistered pens appear swarming, engaged in an endless tracing of randomised pathways, and the video evokes the feeling that one is peering over drone footage from some type of absurdist and dystopian factory floor.

Indeed the entire work is suffused with theses types of sinister resonances, drawing our attention to the increasing dehumanisation of contemporary work spaces, where fleshy bodies are becoming rapidly replaced by their machine and algorithmic superiors. As such, although the presentation of the work is very firmly grounded in traditional forms of art making (drawing, found sculpture), its power lies in how it deftly connects to current issues of technological, and especially computational, automation. Of course one of the main problematics that these issues present is that they are inherently invisible processes; computer algorithms, for the most part, exist simply as a series of unseen protocols. Here the inherently haptic nature of Kelleher’s piece – with its emphasis on the act of drawing from a set of disembodied hands – seems to strive to resurrect the notion of materiality that the march of technological systems occlude. It grants a type of tangible visibility to those impenetrably complex and ungraspable liquid (metal) forces which relentlessly appear to be enveloping all aspects of contemporary reality.

This concept of overwhelming control manifests itself visually within the installation in the form of the rusted cage. However, rather than refer to it as such, the artefact is instead repeatedly described (within the artist statement, as well as the audio recording) as a grid. As Rosalind Krauss famously noted, the grid exists as one of the principal structures of visual modernity, and within the art history of the twentieth-century it came to represent the epitome of order, the final form of human mastery over a chaotic world.[1] Kelleher’s work mischievously plays with this concept, as the pens are, of course, tethered to the rungs of the grid, and as such exist at the edges of its matrix of control. The drawings they produce rely heavily on chance (resembling some of the Surrealists’ experiments with automatic drawing techniques), and inhabit a visual form that stubbornly resists any calls to order. As such, the very concept of the control structure of the grid is undermined by the introduction of contingency into the clockwork system.

It is in this action that Labour of the Months offers a potential framework, in aesthetic form, for thinking beyond the rigidness that contemporary technological systems seem to exert over human subjects. Here we are encouraged to reflect on possible ways out, of generating practices (artistic or otherwise) that can lead to the development of partial schisms in seemingly overwhelming nexuses of power. This is what makes Kelleher’s work so fascinating, in that it provides a diagram, in larval form, of a model for future possibilities, that can perhaps be enlarged in order to provide identifiable co-ordinates for correct navigation through the increasingly hostile and technologically augmented ecosystems of our present moment.