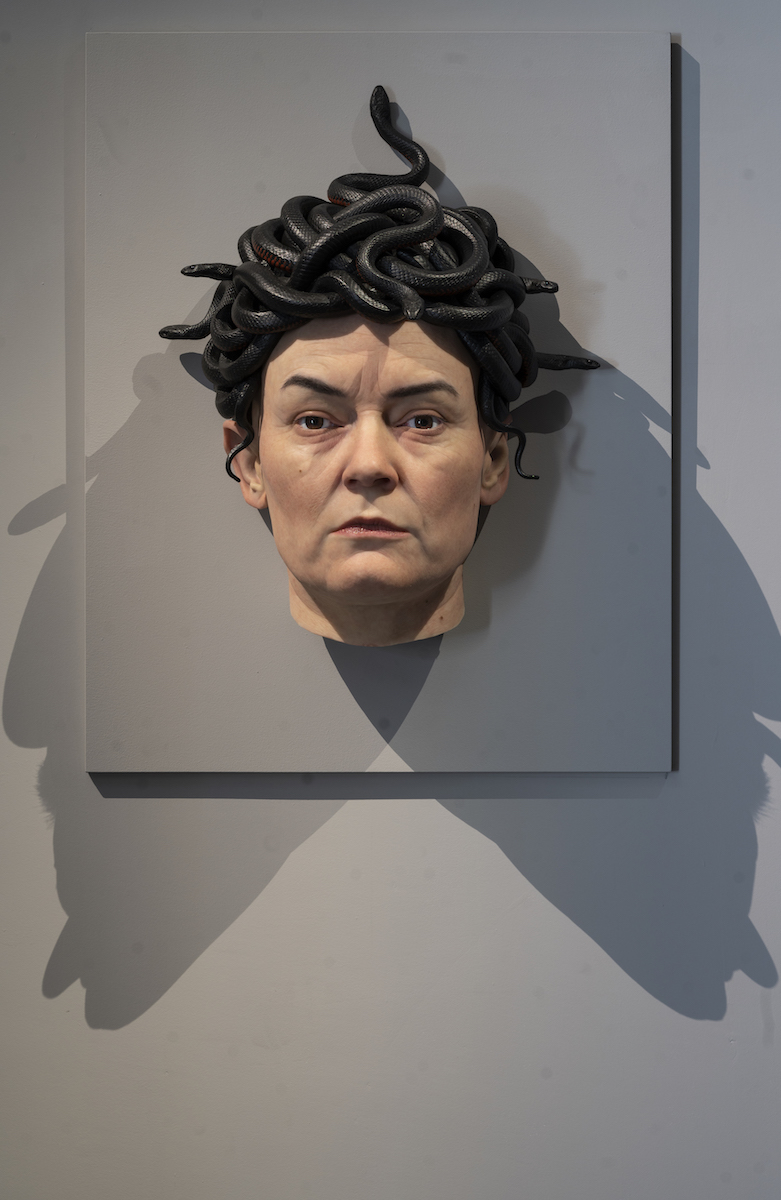

Sam Jinks, In the Flesh, at Galway International Arts Festival

First impressions of this exhibition can be misleading: hyper-realistic sculptures of human figures that could almost be dismissed as mimesis at its most technically brilliant. Surely, art strives to create, not imitate, so if the figures look exactly like real people, where is the art? This question is easily answered when faced with the work in reality for any length of time. The artist has altered the scale of the figures and also directs their gaze downwards so that we are not tempted to peer into their eyes as we might when we meet fellow humans. The changes in scale are one means that ensure we view the work as art and not incredibly crafted mannequins. In this way, distance is created whereby the viewer can engage at a virtual level and contemplate the concept behind the work.

In a society where youth and a plastic perfection of beauty are increasingly valued, this exhibition chronicles both the fragility and the strength of life in its totality, exploring the haunting fact of human embodiment with brute honesty. The figures range from babies through to middle age, old age and finally death. Life and death is exquisitely bridged by the sculpture of Iris, winged goddess who represents the afterlife. And yet Iris, with her resplendent golden wings, is modelled on a normal woman with folds of flesh and pubic hair – two aspects of femaleness that are hidden away like a dirty secret in contemporary visual culture. Similarly, the body of the old man in Still Life (Pieta) affords us a rare opportunity to engage with ourselves and fellow humans as aged flesh, that which the body becomes but is rarely acknowledged. Art is one of the few arenas whereby we can participate with life at this intimate level in all its manifold complexity. Artists open up a world to us and Jinks has achieved this. In the Flesh eternalises a moment whereby we can ponder mortality in a manner that could not otherwise be attained. Not only do we find ourselves in the work, but the lives of others emerge in a spirit of empathy. Are we disturbed? Perhaps, but at least it is transformative.