Making Space at the Galway Arts Centre.

I leave the daylight at the door and step into Galway Arts Centre’s exhibition Making Space. The room is dark. A spotlight shines on the reading area. The low hum of electronic music floats in the air, sneaking out from behind the curtain at the back of the room. The works featured here draw the connection between science and art, as if the artists and scientists involved are tying stars together, creating a new constellation of creativity, hitherto unseen. It is a collaboration between researchers from the Centre of Astronomy at National University of Ireland, Galway and four artists – Louise Manifold, Chloe Brennan, Jane Cassidy, and Treasa O’Brien. It is the work of the latter two that have stayed with me, both of whom have brought a piece of the universe down to street-level, so we can peer into its wonders.

I am standing in the first floor gallery, watching a cosmos in a box change shape. The stars melt into each other and drift away again. Red, burning nebulas appear and then vanish into the blackness. Alien constellations reveal themselves for mere moments, before they too fade into formlessness. This is Cassidy’s Incessant Infinity, a “video mirror sculpture.” Each side of the box is mirrored, so that the film playing within is reflected on all sides and seems to stretch outwards forever. I look into the box through a hole in its top. It is like looking down on the cosmos. Not as a God who exists above it but, rather, like a fortunate spectator who has been gifted with a glimpse at his place in the universe. I know that I am simultaneously somewhere within that film and outside of it. In the midst of all that space there is the world we call Earth. A knot of dramas, romances and thrills among stars.

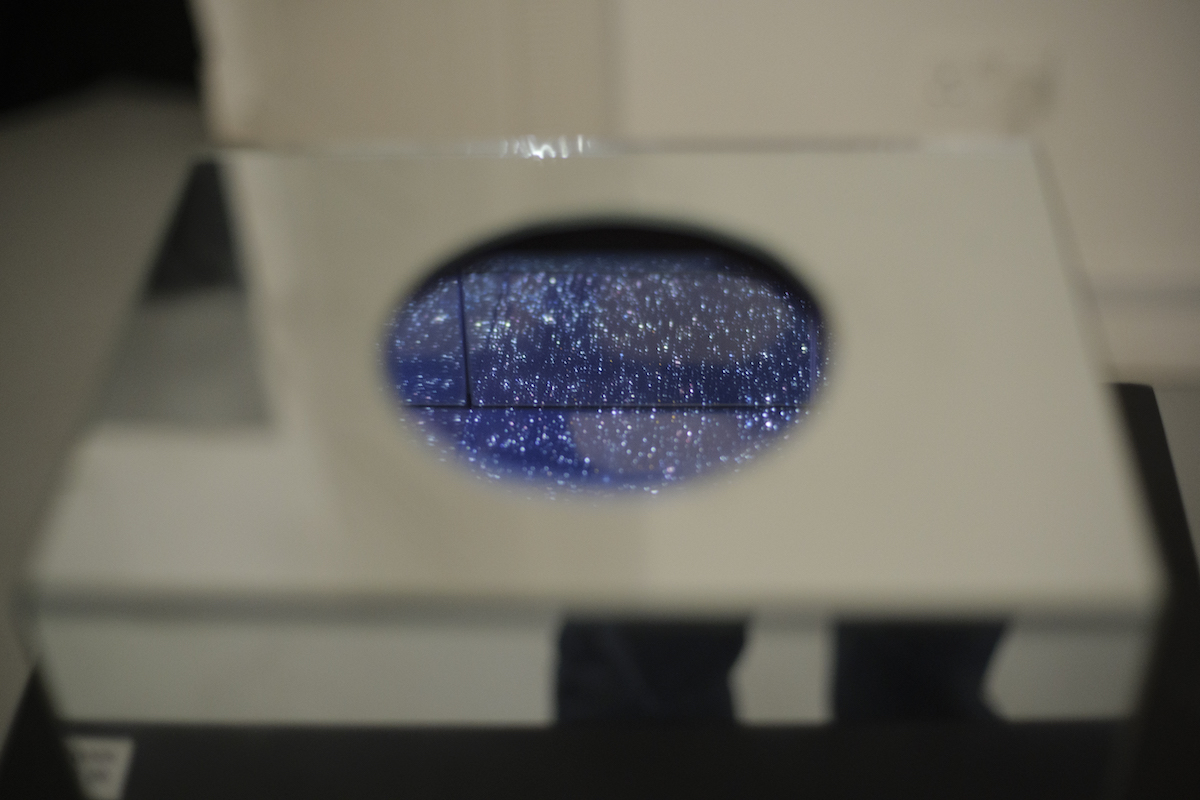

The phrase ‘making space’ usually refers to making space for something else, in effect creating emptiness – the space only exists to be filled by something. This piece of Cassidy’s, however, creates a space around the viewer. Despite its small size, Incessant Infinity is an immersive experience. It seems to reach out of its box and envelop me, wrapping me in light years of dark matter and emptiness. But beside it, on a separate plinth, stands Conamara Chaos, which has the opposite effect. A “video sculpture,” I watch its close-up film of a rocky lunar landscape roll by through a lens shaped like a microscope’s viewer. Strong white light fills my vision, as if it is trying to force its way out through the lens and into the darkened gallery. The lights of Incessant Infinity were small flecks amidst darkness. There was a sense of space to it, of distance and of emptiness. In contrast the light of Conamara Chaos feels like it was stuffed into this tiny piece of art. Every crack and crater in this landscape is filled with it, the light has poured itself into the land, lighting up the very dirt.

Without light there is no space, only emptiness. Emptiness can be perceived without sight. But “space” implies scale, vastness, and place as well as emptiness. All of which require a seeing eye to consume them. And an eye, of course, requires light. But Conamara Chaos proves that while light creates space it also occupies it. I watch this endless landscape roll by for a minute. It is lifeless and stark, but it is not empty; it is pulling me in. At last I look up from the viewer and release the breath I hadn’t realised I was holding. This piece’s claustrophobic power had pushed it back into my chest, where it sat like a gas giant at the bottom of my throat, waiting for me to let it go.

A curtain separates Cassidy’s final work from the rest of the gallery. I push behind it and see the prism of light and smoke floating in the darkness. Its edges are revealed by the swirls of smoke that shift inside them. Without this silver, shining cloud, this piece would be invisible. Only the sphere suspended from the ceiling would be seen. The Light We Can’t See would have then been far too literal a title for it. I step into the prism and turn to face the light. The sphere hangs in the smoke, a lonesome world in a shimmering nebula, while light burns at its edges like the sun’s rays around an eclipse. Ambient synth music hums through the room. I feel my breath escape me as it’s pulled into the smoke which drifts away, and I wait for the machine to belch more smoke into the room. To reveal the frame of the prism once again.

There is nothing to indicate that that sphere is our Earth. It could be any of countless nameless planets scattered throughout the cosmos. I stand and watch the smoke rise from the ground and wind itself about this anonymous world. Despite the fact that it would fit in my fist, I feel dwarfed beside it. If this world is just one among many then so is our own. Planet Earth is no more or less significant, on the universal spectrum, than any other.

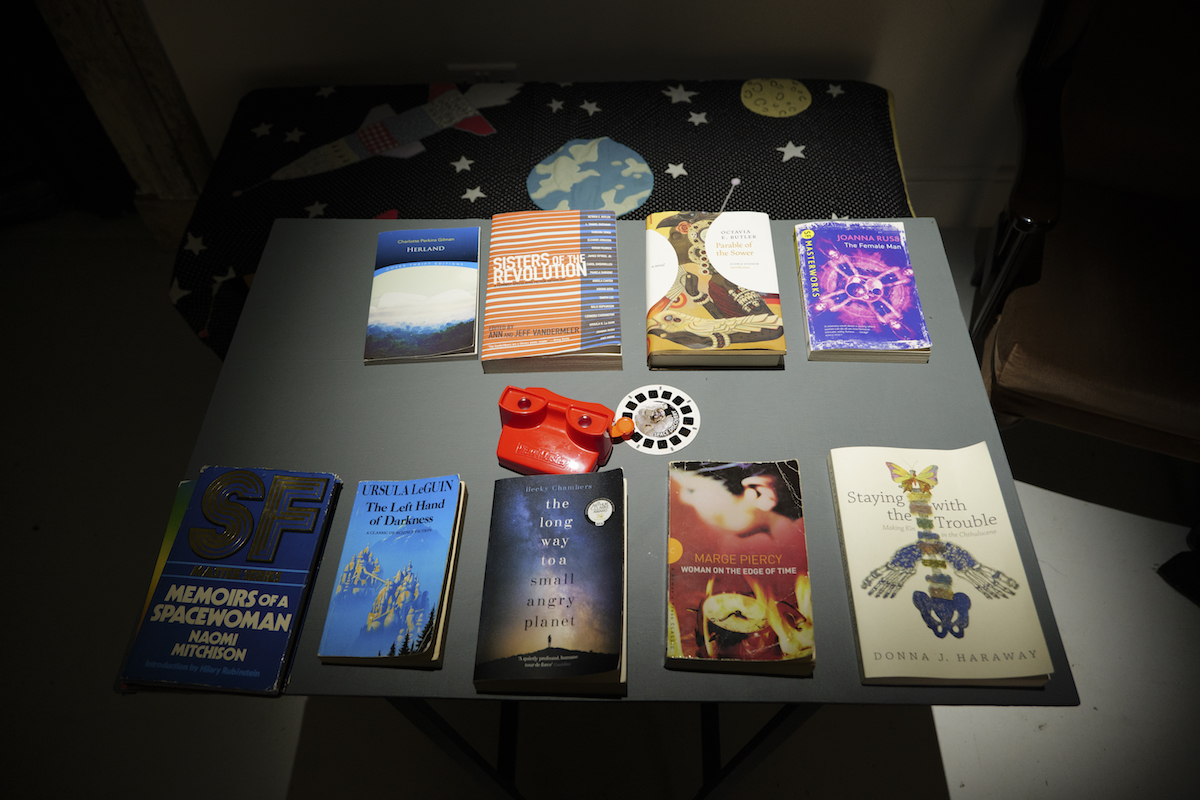

The smoke drifts away again. I walk into the main exhibition room. Science-fiction novels are arranged on a table in the reading area – The Female Man by Joanna Russ, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, Memoirs of a Spacewoman. These texts influenced Treasa O’Brien when she made Memoirs of a Spacemother: an Astropoetic Sci Fi Essay, a film that tells the story of Ceres.

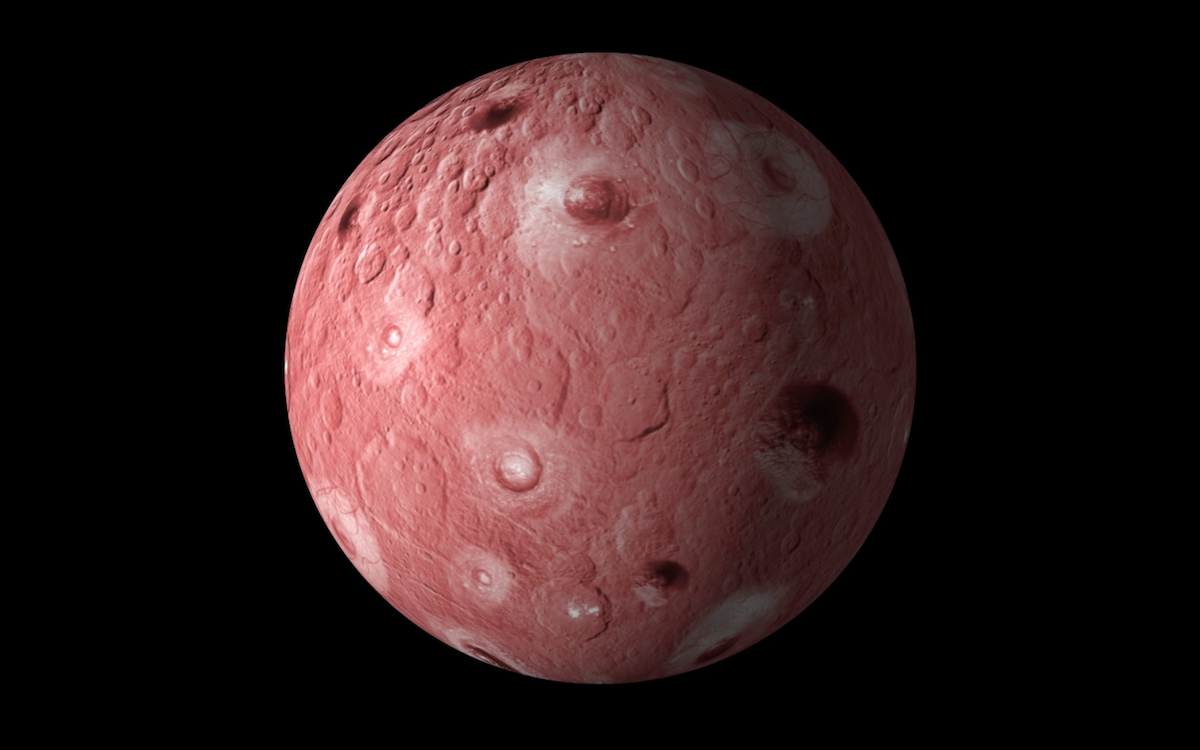

Ceres is a fictional planet that was founded after consumerism destroyed this Earth. On this world the people have centred their culture around “the act of mothering”. O’Brien superimposes films of a breast-feeding baby over the moon and a galaxy. The universe forms the backdrop to a baby’s birth. A human infant appears throughout the film, crawling on the surface of a desolate planet and on a playmat decorated with planets and moons, stars and spaceships. I watch the film lying in a hammock, looking up at the ceiling it’s projected on. It juxtaposes the vastness and emptiness of the universe with motherhood, the most intimate of human undertakings. The word itself encompasses caring, love, learning, and growth, as well as many more of humanity’s finest qualities. O’Brien’s film, her sole contribution to Making Space aside from the reading area, also places mankind within the cosmos. However the film is warm, where Cassidy’s work could be seen as alienating (though I find it peaceful). Ceres has thrived in this hostile and inhuman universe. It orbits our sun, a nugget of peace and harmony that was born of greed and selfishness and hurt. The people of O’Brien’s utopia found a space for themselves. Then, they made something of it.

Making Space is about that making something of space. Cassidy’s work uses the cosmos to convey a sense of potential. Incessant Infinity and The Light We Can’t See are representations of the scope of the universe. Within its vastness anything is possible. Memoirs of a Spacemother: an Astropoetic Sci Fi Essay, however, fills that vastness with belonging, closeness, and caring. Before these artists began crafting their work there was only emptiness. Now there is hope and the potential for more of it. They have made something of space.