Staying close to home Peter Murray joined the What is an Island? event on July 30th (courtesy of BAVA, DIT/ GradCAM, Uilinn and CREATE). The voyage took him to three islands off the coast of West Cork accompanied by a (motley) crew of artists, musicians, researchers and thinkers along the way. Here, he reports on an intense day of art actions, research and reflections, all focused on how islands are faring in the 21st century.

This “durational artistic research event” took place on Monday 30th July, with seventy or so participants assembling on Baltimore Pier at noon, and embarking on the ferry to Sherkin Island. The event involved visiting three islands in Roaringwater Bay; Sherkin, Heir and Long Island. In concept it was not unlike Richard de Marco’s voyages in the 1970’s, in which de Marco led a group of curators, artists and writers to the Hebrides and other islands. This voyage, although less dramatic and lasting nine hours, was by turns fascinating and enlightening.

Once everyone was on board, Ann Davoren, director of the West Cork Arts Centre introduced Glenn Loughran, who leads the DIT/Sherkin Island BA in Visual Art. Loughran explained that the event was intended as a performative questioning of life on an island, within the context of Brexit and globalisation. Unfortunately, the Tannoy system on the newly-acquired Norwegian ferry packed up just as Glenn was about to give his talk and everyone had go below-decks, to hear his introduction. The first speaker was Pat Tanner, a marine archaeologist and shipwright who gave a talk entitled “What is a Boat?”. Weaving in aspects of island life, both in term of Ireland as an island and also the archipelago of islands in West Cork, Tanner showed how the village of Baltimore is connected to the sea, and how the port of Cork, also closely connected to maritime traffic, is changing and evolving. He noted that as ports and harbours are developing people are losing sight of the sea. For instance, in Cork nowadays, nearly all freight traffic takes place on Little Island, in a facility that can handle a thousand shipping container–and the size of container ships is growing. Tanner defined the difference between a boat and a ship. We might have been heading to Sherkin Island on a ferryboat, but it was also clearly a small ship. He offered a simple definition: a ship can carry a boat, but not vice versa. He went on to outline the development of boats, from Syrian fishermen thousands of years ago floating on rafts made from inflated cows bladders, to boats made of reeds or rushes on a wooden frame, to the Hanseatic cogs of medieval Europe. Tanner’s presentation was both expert and detailed: As he related it, the classic Irish currach, made with animal skins stretched over a wooden frame, goes back to the Bronze Age but has been revived in recent decades; the frames are now generally covered in a fibreglass skin. Tanner showed a drawing by a Captain Phillips of boats used by the ‘wild Irish’ in 1648. The boat was, evidently, quite sophisticated. He went on to show log boats from Borneo, and planked boats, both stitched and nailed and caulked with wool and moss. Those with overlapping planks are known as clinker-buit. Tanner divided boats into two classes: shell-based or frame based. In a clinker-built boat, the skin is built first, and the frame added; with a frame-built boat it’s the other way around. As evidenced by examples he showed how variations in design are a result of differing sea conditions, as well as materials and tools available to the shipwright.

A ship, as Tanner explained, is the most complex system of construction that moves, that has ever been built by man. Tanner’s mission is to record traditional boats, and often he has to work from one surviving example, found rotting in a harbour or estuary. From this work, over the past decade has emerged the “Traditional Boats of Ireland” project. Initially Tanner and his team did the surveying by hand, measuring the compound curvature of a hull from a centre line stretched the length of the boat. Measuring by hand, then using the data to make line plans might take six days. Now, using up to date scanning technology, a boat can be surveyed in a few hours, measuring individual planks to within a few millimetres and amassing terabytes of information. Tanner has surveyed over one thousand boats in different parts of Ireland.[1] From this digital information, a table of offsets, a line plan, a construction drawing and sail plan can all be derived and from these scans and digital restorations a full-size replica can now be built anywhere in the world—indeed a traditional Heir Island lobster boat, found in Old Court boatyard, has recently been built in Maine. While observing that some types of craft, such as the Kinsale Hooker–made redundant in the 19th century by faster English mackerel boats–have vanished entirely and are now known only through ship models, Tanner also mentioned that no funding from any government source is available to rebuild or restore historic boats, while his own researches are also not funded by government.

When we land on Sherkin, there is a twenty minute walk to the location where an installation by Mona O’Driscoll is presented in a small gallery space. Specially commissioned for this Archipelago event, Mona O’Driscoll’s installation includes printouts from echo sounders showing the sea floor alongside prints of her own heartbeat, taken with an ECG. Living on the island, with its long tradition of sea fishing, means that Mona, more than others, understands the economics of making a living from the sea. Using redundant technologies her installation is both a commentary on the industrialisation of fishing, with ever larger trawlers, and the loss to the local community of part of its history as fishing becomes less important to the local economy.

We then walk a mile or so to the Islander’s Rest Hotel, where on a large video screen Jonathan Pugh, in Newcastle University, gives a talk via an internet link. Pugh, well known in academic circles, writes on island life, governance and island studies.[2] His talk outlined islands in relation to the Anthropocene, how they are never really isolated but are ‘relational spaces’. Academics move in trends and phases, and Pugh’s areas of research, initially seen by his colleagues as something of a dead-end, or, as he put it, “career suicide” are now a hot topic in academe. Pugh sees islands not as insular, Robinson Crusoe-like places, but connected. He cited examples of literature, such as The Man Who Loved Islands by D.H. Lawrence, and also quoted John Donne’s poem No Man is an Island.

No man is an island entire of itself, every man

is a piece of the continent, a part of the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe

is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as

well as any manner of thy friends or of thine

own were; any man’s death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

Over the years, Pugh has worked mainly in the Caribbean and has been involved with cross-island networks there, with fishing communities, and also forming workers’ unions. His talk delved back in history and enumerated certain facts; The UK has six thousand islands; Canada is really best described as an archipelago. Australia has eight thousand islands, while the Pacific has over twenty five thousand. How many islands are there around Ireland? David Walsh, an enthusiast in such matters, has visited over five hundred so far. Pugh talked about the Anthropocene, and how islands are being formed in the Pacific made entirely of plastic waste. Wind farms, military bases; islands are constantly forming and disappearing. He cited SIDS (Small Island Development States), a group of small islands, mainly in the Caribbean, that share information and expertise in terms of providing a future for island communities. Islands are not isolated, is Pugh’s message, they are intricately interconnected. In the Cork context the mention of SIDS evoked laughter in the audience as this is also the acronym for the Sherkin Island Development Society. Pugh quoted Kamau Brathwaite, a poet and academic from Barbados who wonders why Caribbean island psychology is not dialectic, in the way that Western philosophy has assumed people’s lives should be. Brathwaite posits instead a philosophy of ‘tidalectic’, where people are in a continuum, constantly meeting, encountering, then receding, in a fluid state. Pugh also quoted Édouard Glissant’s The Poetics of Relation:

I have always imagined that these depths navigate a path beneath the sea in the west and the ocean in the east and that, though we are separated each in our own Plantation, then how green balls and chains have rolled beneath from one island to the next, weaving shared rivers that we shall open up when it is our time and where we shall take our boats. From where I stand I see Saint Lucia on the horizon. Thus, step by step, calling up the expanse, I am able to realise this seabow.

Pugh then showed a video of a Barbados Landship, a dance—or more properly a series of rehearsed manoeuvres—that developed in the nineteenth century. Dressed in the uniforms of naval officers, soldiers and nurses, the dance parodies hierarchies of colonial rule, but also seems to suggest that rules are necessary for an orderly society. Much more than a dance, Barbados Landship is also a mutual protection society, or co-operative, formed in 1863, and still a significant cultural and social movement today. Pugh described it as tidalectic, noting that it played an important role in Barbados history, after emancipation and independence. When slaves were emancipated, the slave owners were compensated, but not the slaves. Landships exist in the eleven parishes of Barbados, and the music, provided by ‘Tuk Bands’ derives from Scottish and Irish tunes, mixed with African rhythms. But Tuk music also evokes the rhythm of steamships, speeding up and slowing down. Some of the moves, such as ‘Wangle Low’, derive from life on board ship. Limbo dancing also comes from slave ships, where slaves were forced into low ceilinged spaces. The characters in Barbados Landship are named after ships: Rodney, Iron Duke, Queen Victoria, etc, while the characters also include doctor, matron and engineer. At the end of the dance, the performers are ‘piped’ off the floor by naval officers to the insistent beat of a drum and a high pitched whistle. Pugh then spoke about the President of the International Small Island Studies Association, Godfrey Baldacchio, who holds that islands are “part of complex and cross-cutting systems of regional and global interaction”.

A brief review of mankind’s transferring from the Holocene to the Anthropocene then followed. Pugh was clear in his ideas: “Nuclear radiation has encircled the globe. We’ve ticked all the boxes that the Royal Geological Society has identified as marking the transition into the Anthropocene. Pure nature is now impossible. Everything has been transformed”. He cited the most recent Islands of the World conference, which took place in Holland. The delegates were brought to what was described as a ‘nature island’, but Pugh pointed out that in the Anthropocene, there is no part of that island that has not been touched by pollution or litter. He emphasised that there is no “outside” to global warming, and global warming does not unfold all at once: in some places it is slow, in others, much more rapid. Recent hurricanes in the Caribbean have increased in intensity. Global warming takes place in non-linear time. There are short-term events (such as tsunamis and hurricanes), and there are also gradual changes that take a thousand years. “We were previously thinking of interconnections. Now we have to think of slow times, immediate times, of different time lines”. The politics of all this concerns Pugh: “Over the years, island living has been romanticised. But in recent times against the backdrop of global warming (and perhaps as an alternative to the pressures of high density urban living) the island has once again has been romanticised. Island inhabitants are being celebrated… something which suits powerful interests who like to imagine that indigenous peoples are more in tune with the environment—the romantic figure of the indigenous islander, in tune with nature. But this image is problematic. The islanders do not see themselves as being particularly resilient, and resent this labelling: “We’re resilient, but the pollution is coming from the big continents”. Pugh said that labelling islanders as tough and enduring can actually assist in permitting further exploitation and degradation of islands. Islanders have a lot to teach people, he said, but as he points out. “It’s a bit of trap, lots of politically-correct people are saying ‘they’re great’, but this means powerful interests can shirk their responsibilities”.

A few people asked questions at the end of the talk. One woman, who lives on Sherkin, offered the argument that if islanders did not have to put so much energy into getting funding for projects, life would be easier. Pugh responded that “Islanders tick the funders’ boxes”. But what worries him is that there is a narrow way of framing such funding. His main point was that islands should be talking to islands.

The audience then de-camped from the Hotel, walking down to the pier below, and embarking once again on “Dún na Séad”, to head for Long Island, in Roaringwater Bay. During this voyage, Mick Wilson, a graduate of NCAD, and now a professor at the Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg, read a text, or extended meditation, on island life, entitled “Art and the Archipelagic Imaginary”.[3] Wilson began by mentioning that the word for island in Swedish is “the solitary vowel ö”. He cited Édouard Glissant, calling for a renewal of poetics relating to the earth. “Island, sea, island, sea…”, then talked about the extermination of indigenous peoples, such as Caribs and Arawaks, and the appropriation of islands in the Caribbean by European colonists. As our ferry battled through sun-sparkled surf, Wilson read from the poem Night Ferry and talked about the term ‘creole’. He listed the sufferings of indigenous peoples under colonial rule: the rocks we passed at this point were appropriately named ‘the Catalogues’. Wilson also referenced the 2002 Documenta exhibition, curated by Okwui Enwezor, and talked about the contribution of writers such as Glissant, who was born on Martinique Island and attended the same school as Aimé Césaire, ( a poet, author and politician from Martinique), and Léon Damas (also a poet and politician). As Wilson clarified, it was Glissant who posited the term “Archipelagic’, offering this as an alternative to ‘mondialité’. Wilson went on to reference Jamaican dub poet Mikey Smith, who was murdered by political opponents in 1983. In dedicating his Poetics of Relation to “Michael Smith, assassinated poet”, Glissant had remarked upon “the archipelagos laden with palpable death”. Wilson cited also “Archipelago Logic”, a conference held in Turku in 2011, offering the idea that the term archipelago was moving from metaphor to allegory. He pointed out that the term ‘archipelago’, while based on the language of ancient Greece and Rome, is in fact of more recent invention. To quote directly from Wilson:

“The term ‘archipelago’ can be broken down into the roots “arch” (the Greek signifying ‘original’, ‘principal’) and “pelago” (a Latin derivation from an earlier Greek term meaning an open sea, a pool, a gulf, even an abyss, the sense of being out upon the high seas). It is not an ancient Greek word, but an early modern Italian word made of these Greek borrowings. The elements of the word are Greek, but there is no record of arkhipelagos in Ancient or Medieval Greek (the modern word in Greek is borrowed back from Italian). From the 13th century the term appears as the name for the Aegean Sea – the principle sea that washes between the Italian and the greater Greek peninsulas. The Aegean being full of island chains, the meaning was extended in Italian to ‘any sea studded with islands’, and the word then migrated and mixed across other languages”.

Wilson cited this compressed history of the word archipelago, by way of pointing to the ‘generative transfers and slippages of language mixtures, of creolisations’. His talk on art and islands prepared the participants for the next stage in the event.

The ferry came in to the pier at Long Island and everyone disembarked, in anticipation of the next event, titled IMRAMM and led by a group known as “Art Manoeuvres”. Stretched out along the pier was a long blue rope. After a few minutes it became clear what was to be done. The seventy participants picked up the rope, and holding onto it, walked two-by-two for a mile or so, from the pier where the ferry landed, to a westernmost point where the Atlantic formed a sharp horizon. All participants had been issued with small radio receivers and earphones. Two mediators, Peter Tann and Moze Jacobs, spoke alternately, offering ideas and raising queries. [4]

As we walked in a long line along the narrow road, we were tugged forward one minute, then pulled back the next, but after a while we began to walk in perfect unison. The rope connected people, but also controlled and separated us. No group could form, there was no falling back, no running forward. The rope guided and became a support, but contained also resonances of imprisonment, or enslavement, of being harried along. “We did not know where we were going” said the narrator in our earphone “. . . Trust me, I have no idea where you are going. . . Hold the rope, many have fallen into the heavens below.” This became a mantra, and was repeated as we walked. At the end of the walk, a tug of war ensued, with some at the head of the rope line seeking to go onto a small pier, while others resisted. Then everyone lay down in the grass and enjoyed the sunshine and the view of Fastnet Rock on the horizon.

While the “Dún na Séad” ploughed its way back through Roaringwater Bay, towards Heir Island, the sun setting in its wake, Eimear Deane, a key figure in Ireland’s Brexit negotiating team in Brussels, spoke about “The Gini Co-efficient”, a statistical tool that provides a picture of wealth distribution, adding the unsurprising news that the Gini gap in the UK between rich and poor is the largest among developed nations. Voters in the UK who opted to leave the EU were concerned with this gap, with globalisation, and also with immigration, and so fell back on simple geography as an unfailing support. They sought the certainty that comes from an insular location, Deane explained, but geography is not a matter of choice. Britain and Ireland are inescapable parts of an archipelago. In July 2000, the then Enterprise Minister Mary Harney posed the question, regarding Ireland’s fealty, was it to Boston or Berlin? In the end, Deane posited, it is both, and in a neat analogy that would appeal to suburban residents, she described one as our front garden and the other as our back yard. As the smaller of two islands, she said, on the whole life in Ireland has been tough, citing history from the Tudor and Elizabethan periods; through the Great Famine, to the Civil War and the Troubles. Deane added that the Irish aspiration is for a settlement that would respect geography, but not be bound by it.

She described some of the achievements of the Good Friday Agreement, including cross-border co-operation, particularly in health and social services, where the border between North and South has become almost an anachronism. “If we don’t act as an island” Deane continued “we will lower the standard of living for everyone”. This mantra of a safe berth, of common sense and prosperity happily united, may be itself anachronistic at a time when voters doggedly maintain positions they know will result in impoverishment, while the failure of the EU to respond to concerns regarding sovereignty was also markedly absent from Deane’s talk. But her points were valid: the peace process had made Ireland north and south work more effectively for all people living on the island. The Good Friday Agreement came at a time of optimism, when borders were dissolving all over Europe: ”Sadly, the UK has decided to leave the EU, but Ireland is and will remain a part of Europe”. In Ireland, she added, we have always seen that multi-lateralism is important. Although small islands tend to be outward looking, Brexit now presents a challenge to that way of thinking. “I am working with my colleagues in Europe” Deane said, “to ensure an orderly withdrawal . . . people, programmes and the border are the three priorities. We want to protect the over four million people whose rights of residency will be affected by the UK’s leaving the EU. We want to protect the projects and programmes that were undertaken… at least until the end of 2020. And we’re trying to find a way to ensure that Brexit doesn’t end the Good Friday Agreement. However, the fact that there will be a border is impossible to avoid. The Irish government has announced that we will be employing eight hundred new customs officials. With Brexit, borders will go up. A hard Brexit is incompatible with the Good Friday Agreement—unless a special case is made for Northern Ireland”, Deane went on “But Northern Ireland has a particular relationship with the Republic of Ireland that is inescapable”.

On either side of the ferry, as we headed through Roaringwater Bay, white surf pounding against the jagged rocks that abound in this part of West Cork, clouds loomed overhead ominously, and the spray from the prow mixed with drops of rain. Deane continued, her voice transmitting over the ferryboat Tannoy, which was now working again. “Products coming from the island of Britain. Plant and animal diseases do not recognise borders, so some products coming from the island of Britain over to Northern Ireland have to be checked”. Here, Deane seemed to be slightly clutching at straws. . .“Decisions now should be island-sensible” she continued, and with a note of optimism, “other countries recognise the importance of the Peace process. That is how it is seen in France and Germany. But within the EU, some countries will feel less safe without the UK. Some countries bordering Russia are nervous about losing Britain’s protection. As we face this it is obvious that our relationship with Britain is special. One of the first objectives we sought to preserve was the Common Travel Area, and happily our EU friends have agreed to this. But in leaving the EU, Britain is leaving Ireland. There is an anger in the UK when we describe Ireland as part of Europe. Right now, there is a huge amount of political attention on Ireland. However, the suite of high-level visits to Ireland in recent months, including Harry and Megan, Charles and Camilla, cannot hide the fact that Ireland is part of Europe. The relationship between Britain and Ireland cannot be romanticised or fixed, although those human contacts are very important in their own way. With Brexit comes barriers. With Brexit comes a threat to our Peace Process. We need to help Great Britain to realign their history, their politics”.

Landing at the pier in Heir Island, we walked up the road, bounded by high hedges, to what has evolved over recent years into a small campus of buildings, at the centre of which is the legendary Island Cottage restaurant run by John and Ellmary Desmond. A new, and very fine, gallery space contained a semi-permanent exhibition of paintings by John Desmond. A quartet of musicians, led by the indefatigable Katy Salvidge, and including cellist Tess Leak, deliberated as to whether to play indoors or out. The audience swayed back and forth indecisively. In the end it was decided to play in the open air, beneath a banner with the words “our boats are open, and we sail them for everyone”. Floating music composed by Justin Grounds and Tess Leak, occasionally (but intentionally) discordant, flowed around and through the landscape and buildings.

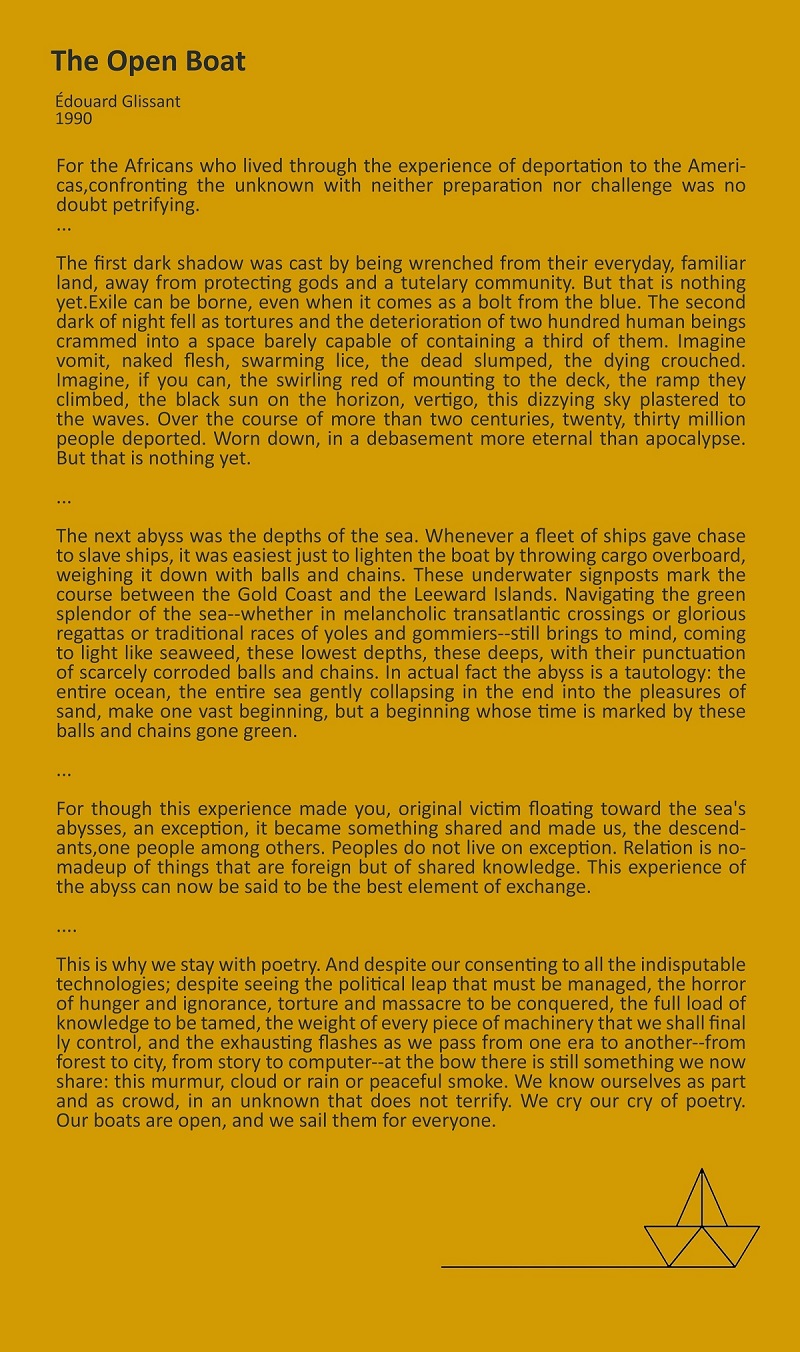

As the heavy rain clouds rolled overhead, Leak played cello; Before the piece began, Justin explained how it worked. Each player was given seven fragments of music, eight bars long. These fragments could be played as many times as the players chose, coming in and leaving the composition at different points. The music began with a piper playing the first variation repeatedly; then each of the other musicians joined in when they sensed it was appropriate. This informal conversation between instruments continued for some twenty minutes. By reducing the number of notes, and by dint of constant repetition, the piece acquired an element of Zen and fragments of traditional melodies seemed to lie hidden within the music. Justin explained that the composition was inspired by the writings of the, by now familiar, Édouard Glissant:

We know ourselves as part and as crowd,

In an unknown that does not terrify.

We cry our cry of poetry,

Our boats are open, and we sail them for everyone.

Copies of the score were distributed amongst members of the audience, who could walk in and amongst the performers as the piece progressed. Justin described the music as inspired by punk, but it did not seem reminiscent of the immortal Johnny Rotten or Sid Vicious. The simple and haunting music reminded this writer of Jean Rudy Perrault, whose compositions commemorate Haiti, his island homeland. [5]

On the half hour voyage back to Baltimore, we were served an excellent chickpea stew dinner on board “Dún na Séad”, and Richard Kearney spoke for twenty minutes, drawing together many of the threads of the day, and providing a context for the celebration of the islands off the west coast of Ireland in literature and folklore. He described the ‘circumnavigatio’, a pilgrimage on the high seas, undertaken by Irish monks, who would go from one island to another. He spoke about St. Brendan, who had discovered Nova Scotia, and whose epic voyage had been re-created by Tim Severin in 1976. Our own circumnavigation took us back the way we had come, past Heir Island and Cunnamore, towards Baltimore Harbour, on the ebb tide. Kearney talked about the island of Bridget, Oileán Bridget, which once had a well. On one tragic day, a boat capsized and all aboard were drowned; the well on the island is said to have dried up on that day. Recently, he added, the well has been re-discovered and pilgrims now visit this island again. He then read a poem he had written in 1991, inspired by a visit to Oileán Bridget. The poem evoked times long gone, with references to sea voyagers, an mhaighdean mara, oystercatchers and St. Bridget’s Well. Kearney spoke about the tradition of Imram, of undertaking a pilgrimage to islands. This could be a circumnavigation: if a “white circumnavigation”, you headed out to the Western Isles, and never came back. But if it was green, you hit land, and made your pilgrimage. White and Green. Kearney’s talk had many resonances, not least in relation to the rope-walk on Long Island. He quoted George Bernard Shaw on the insular nature of the relationship between Britain and Ireland, and posited that life should be lived not in an insular nation but in an archipelagic nation. “Archipelago does not accept the border; we have to think beyond sovereignty”. As John Hume said, “it’s time to think post-nationally”.

It was Kearney who elaborated on how Islands have played an important role in Irish literature. John Millington Synge was encouraged by Yeats to go to the Aran Islands, and wrote “Playboy of the Western World”. Yeats was entranced by the mystical island Inis Cealtra or Holy Island on Lough Derg, writing about it in his poem The Pilgrim. Kearney also cited Seamus Heaney and Paul Muldoon as poets who have been inspired by islands, and he did not forget Tom Murphy’s Sailing to an Island, nor Peig Sayers, nor the writings of Tomas O’Flaherty. For the EU’s “Bureau of Lesser Used Languages”, John Hume had written a report, in which he posited a Europe of small regional centres. The nation state was too big, Hume thought, and he proposed instead an archipelago, one that was relational, that refused fixed borders. Kearney echoed Eimear Deane’s appeal that ways of thinking cannot be insular, but observed that a move towards nationalism in both Europe and America is a reality that has to be faced.

Overall the day was a great success, with a huge amount of effort put into organising and catering for the seventy participants, and a wide range of artistic, cultural and political offerings. Walking through Skibbereen later that evening, I stopped by the window of Charles McCarthy estate agent. One of the islands we had passed, West Skeam, I was interested to see was for sale, for €1.6 million. Nearby Horse Island is also for sale, at €6.75m. The hotel on Sherkin Island, where Pugh gave his talk, has been recently acquired, for c €1.5m, by an Irish company, with Chinese business interests. One of the realities of life in this unique part of Ireland is that it is transforming, from being a utopian escape for artists and writers, into a playground for the wealthy. Gates that were once open, are now quietly padlocked. A landscape once characterised by ruined farmhouses is now dotted with fine new houses. The intensification of farming, both on land and in the sea, the success of the Wild Atlantic Way tourist initiative, and the influx of a new level of recreational wealth and investment, are all competing for a slice of the fragile magic that is West Cork. ‘The island as Real Estate’ may not have been to the fore of the day’s proceedings but, perhaps that was for the best.