Theresa Nanigian, Just a Bit Extraordinary

The Highlanes Gallery, Drogheda, 22 September – 7 November

The experience of watching the process to confirm Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court, in the face of significant allegations of sexual assault and Trump’s mocking of #MeToo, was disturbing, to say the least; especially when such absurdities as a decades old calendar were produced as evidence. You could be forgiven for thinking you were watching reality TV rather than the selection process to appoint a judge to the highest office in the land. But then again, having observed the often bizarre, physical interactions that Trump has had with world leaders and dignitaries, not to mention his regular, outrageous comments on gender, race, immigrants (and the list goes on), Kavanaugh’s behaviour during the confirmation was mild by comparison.

I was reminded of this when viewing Theresa Nanigian’s current exhibition, just a bit extraordinary, at the Highlanes Gallery, County Louth. Nanigian’s practice is described as, ‘creating portraits of contemporary Western life, be it a profile of a single individual, a catastrophic event, or an entire country’ and that her representations draw upon ‘the analytical systems, tools, and aesthetics of other disciplines such as sociology, economics, psychology and logic’. The exhibition is divided into three chapters in which the artist explores the ‘expression of identity across the lifespan’. Each chapter has previously been exhibited as a single body of work but they are now brought together in the Highlanes, and the exhibition here includes photographs, video and text. One piece that struck me is an audio work entitled Freak Show. The listener is exhorted to hurry to buy a ticket to the “show” in which, amongst others, there is a bearded woman. It made me think of how Christine Blasey Ford was being treated. The male in this instance exhorting the public to come along and see this ‘freak’, the bearded woman. It’s perhaps this theme of the supposedly strange that resonated most for me in our troubled times.

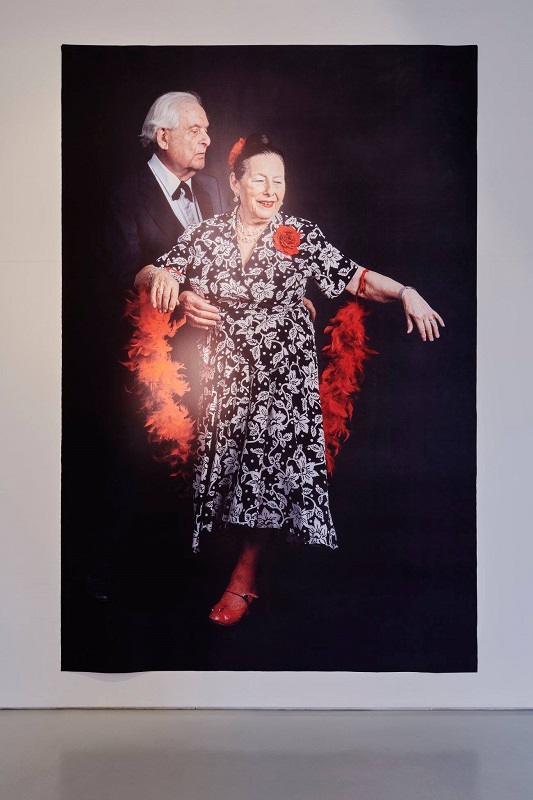

The exhibition begins in the reception area of the gallery where the visitor is greeted by a large photographic print of Jeff. Making your way to the lower floor you pass an even larger print of Lindsay (though I was informed by an attendant that actually the subject of the photo is quite small!). When you eventually arrive downstairs the number, the physical scale and the sheer presence of the photographic prints makes them appear to really ‘occupy’ the space.

I was immediately drawn to the dancers who belong to the third chapter of the exhibition, trying to behave. In it, Nanigian explores older age through ‘the bi-monthly tea dances’ at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, which she attended on numerous occasions to observe, film and survey the patrons. According to the information provided, through this process she ‘uncovered several dichotomies…composure and vulnerability; vivaciousness and feebleness; spirit and neediness; beauty and decline’. These dichotomies are continued in the photographic work too. There is a warmth and humanity about them, a gentleness; a joy in the closeness the subjects share through the dance. They know they are being photographed but appear totally at ease, happy and comfortable in each other’s arms. I’m reminded of 20th century anarchist Emma Goldman’s often quoted statement, “If I can’t dance I don’t want to be part of the revolution”. It could be said from those in the photos that, to live life fully, is to dance.

The second chapter, master of my universe, looks at “the middle developmental stage of adulthood”. In it, the artist’s focus is on how the subjects earn a living but the people she has chosen do not have run-of-the-mill occupations; they are vendors on the boardwalk of Venice Beach, California and comprise a diverse range of nationalities, ages and socio-economic status. Their personal narratives recounting how they took up their particular occupation reflects this diversity. Nanigian purchased some of their wares and these make up the inventory, an installation consisting of 31 cases of various sizes. What I loved about several of them was that they were made from recycled materials. The fighter jet aeroplane made from discarded drink cans; the wind chime made from a confectionary sugar shaker with long spoons used for ice tea as the chimes; and the paintings of Marilyn Monroe and David Bowie on broken skate boards. The people who made this art don’t indulge the disposability of consumerism, but instead take a resourceful approach to reusing and recycling.

The text panel for this chapter (as for the other two chapters) conveyed an insight into the individual’s outlook on life. Just one example; “an American citizen watching my country become a fascist regime – scared at the lack of compassion people have for each other – a mother finally starting to feel comfortable in my own skin – privileged – not powerless – coming to realise that hard work does not pay off”. The subjects were responding to the prompt, “I am”, and the title of the exhibition just a bit extraordinary comes from the response of one of the photographed sitter’s. Through just a few words and short phrases, we can tell more about a person and the life they’ve lived than long sections of text could ever achieve. Less is often more.

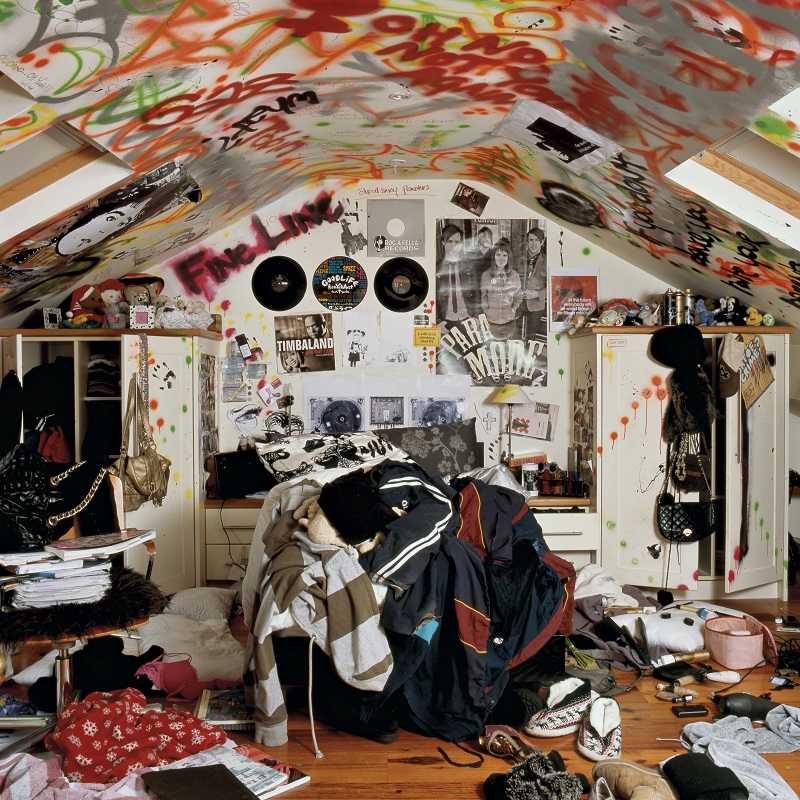

The remaining chapter in the exhibition, not sorry, has as its subject the Irish teenager. Here, Nanigian’s aim was to get behind the very public social networking profiles of the teenagers and into the ‘private territory of the bedroom’ to discover how and what they really thought of themselves and their world rather than how they choose to present themselves to the public. As with the other chapters, their responses are very frank and often brutally honest.

When I first heard the title of the exhibition, just a bit extraordinary, I took the ‘extraordinary’ to mean strange, or bizarre. And maybe to some people the subjects depicted will appear that way. But I view them as very ordinary; the sort of people I like. They are themselves, not what others may wish them to be. They don’t go along with the capitalist work ethic of ‘screwing others’ to make yet another dollar, Euro, or pound, so maybe in that sense they can be described as ‘extraordinary’; they are living their lives the way they want to, not as others would ordain they live them.

Hopefully, in future years, people will view an exhibition that looks back on the world of 2018 and an element of it will be a freak show in which the behaviour and utterances of the likes of Kavanaugh and Trump are regarded, in the famous quote from a former Irish Taoiseach and art aficionado, Charles Haughey, as “grotesque, unbelievable, bizarre, and unprecedented” – instead of those who dare to be different. And by way of a footnote, 28 year old Harnaam Kaur, A British Model, anti- bullying activist, body positive activist, life coach and motivational speaker from London, recently made a Guinness World Record for the woman with the fullest beard. Let’s celebrate the (extra) ordinary.