Lucy Cotter went to the new MoMA to experience the major refurbishment and expansion of the building and the rehanging of the collection. She takes us for a tour and offers her impressions and insights.

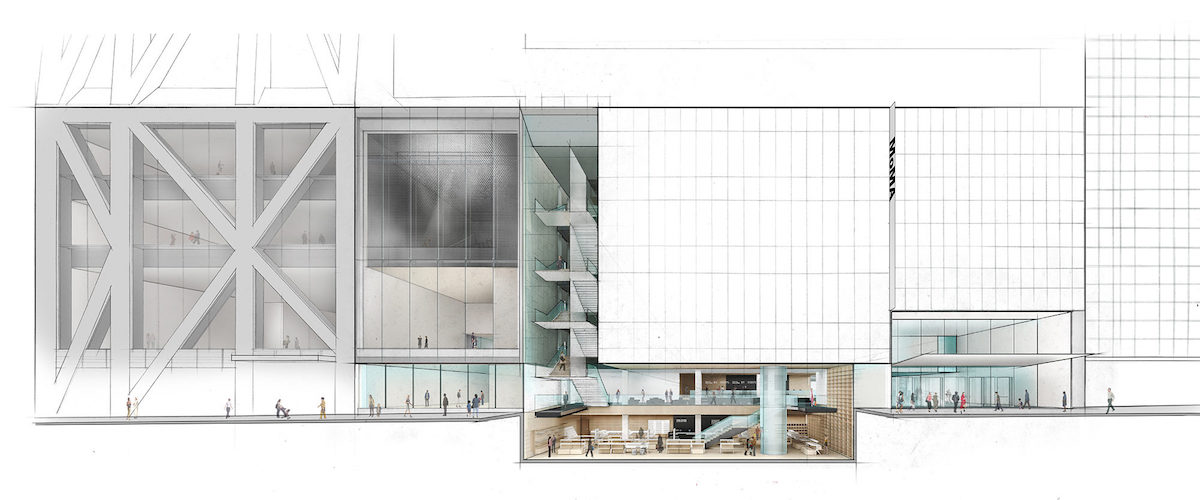

It’s just a few days after the re-opening of the majorly refurbished MoMA and I am in New York, curious to experience the transformed museum in person. There has been a complete rehanging of the collection alongside a 47,000 square-foot expansion by architects Diller Scofido + Refro and Gensler, with a price tag of $450 million. The physical sensation of entering the revamped museum, which is 30% bigger in size, is unexpectedly overwhelming. Standing in the expansive Eames-meets-corporate-style lounge, with a new wing to the left and new lifts to seven exhibitions and three floors of permanent collections to the right, I literally don’t know which way to turn. The row of ticket desks is so long that it resembles an airport check-in. Ditto for the coat checking stations, where an usher makes me walk to the end of the line to exit correctly.

Map in hand, I start my visit upstairs with the most recent works in the permanent collection, where I am most curious about the curatorial selections. En route, I encounter the abstract black and metallic mosaic of Haegue Yang’s stunning new site-specific installation Handles in an atrium that can be seen from several floors. I am lucky to be just in time for one of the hourly performances in which the oversized sculptures are wheeled across the gleaming white floors by black-clad performers, their tiny metal bells ringing as they pass me by. There are several independent spaces dotted through the museum, constructed specifically to house installation art, and one new studio for live art, which currently houses Rainforest V (variation 1) (1973-2015), a sound installation constructed from everyday objects fitted with sonic transducers conceived by David Tudor and realized with his long-term collaborators at Composers Inside Electronics Inc.

While the new presentation of the permanent collection remains chronological, every effort has been made to rid the wall texts of linear art-historical narratives. Instead, works are clustered around open-ended themes, Tate Modern style. The “1970s-present” section, where I start my tour and where I will focus my thoughts opens with a room entitled “Public Images”, which reflects on the media culture of the late ‘70s. It’s slightly disappointing to immediately encounter some of Cindy Sherman’s most iconic photographs, given my expectations of a new selection of works. The room also contains works by Louise Lawler and Dara Birnbaum under the curatorial rubric of engaging with gender in media, but perhaps the decision to open the contemporary art section with three women artists is the most significant subtext here. Overall 28% of the works on display in the ‘new’ MoMA are by women-identifying artists. This is five times the representation of hangings in recent years and it is a major reason for the museum’s spate of recent acquisitions, along with the wish to acquire more works by artists from Southeast Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Japan.

Subsequent rooms unfold another aspect of the changed MoMA – namely that the curators from the six media-led departments have worked together to create interdisciplinary exhibitions. Reflecting on architecture’s capacity to shape social, political and cultural communities, a room entitled “Building Citizens” brings together models by Herzog & de Meuron and drawings by New York mega-architect Peter Eisenman with Chad Friedrich’s film The Prutt-Igoe Myth (2011), reflecting on a failed urban housing scheme, and Amanda William’s Color(ed) Theory (2014-16) photo series that examines the visual and spatial embedding of race in American cities. This clustering also makes space for uncategorizable works like studio Rael San Fratello’s “Borderwall as Architecture” project, which combines conceptual dreaming, critical analysis and architectural proposals as an inseparable whole. One drawing shows the border reconceived as a playground with children on either side sharing cross-border seesaws.

The succession of rooms that follow contain highlights like Wolfgang Tillman’s photos from the ‘90s, which still feel remarkably fresh, and Rineke Dijkstra’s poignant time-based portraits of child asylum seekers from the same period, a series I haven’t seen before. But there seems to be no end to the adjoining spaces and a biennale-style fatigue sets in that is hard to shake. The occasional room dedicated to one work by an artist relieves the conveyer belt presentation style, and the museum would benefit from including more of them. While Richard Serra’s is the first I encounter, another showing the pioneering collective JODI’s charmingly archaic digital project My%Desktop (2002) promises that it is not only the mainstream heavyweights who will be given such honours. The weakest links in the chain are the rooms where the curatorial ideas become woolly or highly neutralizing, diluting the strength of the individual works. This happens for example in “Transfigurations”, where works by women artists with no serious connection between their formal or political interests are grouped with the imprecise justification that they “reimagine how women might be represented”. It’s rather depressing to find Lorraine O’ Grady’s Untitled (Mlle Bourgeois Noire) (1980-83), a radical performance sequence critiquing the bourgeois racism and sexism of the New York art world, as good as lost in this pick-and-mix.

Standing in “Worlds to Come”, I wonder too how a semi-abstract sculpture by Nairy Baghramian could benefit from being juxtaposed with a drawing by Kara Walker or vice versa. Looking at Deana Lawson’s subtle portrait Thai (2009) in the same room, I miss any mention of gender identifications like ‘transgender’ or ‘non-binary’ in the wall text. It’s as if the curatorial team wished to say something but lost the courage to say it directly. While Lawson’s gender-fluid portrait is distanced from contemnporary reality by ostensibly belonging to “worlds to come”, a wall text accompanying Kerry James Marshall’s wonderfully ambiguous portrait of a black police officer from 2015 is torn out of the present by being described in historicizing terms. The wall text insists it “was created at a time when news about police killings of unarmed black men, women, and children was proliferating across the United States”; as if that time had ended and the controversies around police brutality and race evoked by the work are not a burning issue right now in the US.

At moments like this, the curatorial ‘We, as MoMA’ doesn’t make enough space for acknowledging that curators’ choices are situated and subjective. In the 19th century and early 20th century sections of the collection, this presentation style seems to reaffirm the possibility of objective knowledge, undermining how the individual display narratives seek to break away from canonical art history. In the contemporary art section, this anonymity too easily enables discursive exits in the face of politically challenging works. Perhaps the lack of individual authorship available in the collaborative curatorial effort partly undermined the freedom to make more radical curatorial statements. Elsewhere in the museum, a richly provocative retrospective of Chicago-based artist Pope.L. raises questions that are flaming in their urgency amidst the heightened racial tensions of Trump’s America. Here, curator Stuart Comer and assistant curator Danielle A. Jackson have not shied away from Pope.L’s uncontainable radicality, even cutting a slab from the museum walls for one work. In Pope.L’s unforgettable Times Square Crawl (1978), the artist crawls down West Forty-Second Street in a business suit to foreground the rift between the upwardly mobile and the dispossessed communities in America. For A.T.M. Piece (1997), an even more subversive and psychological work, Pope.L ties himself to a bank door with a string of sausages, while wearing nothing but a skirt made of dollars. A response to a new law banning begging near banks, this is one of many works that use artistic agency to unhinge the normalization of structures that entrench black poverty and homelessness.

On my second day at MoMA (you can’t get through the new museum in one day), I stumble on a small one-roomed exhibition, an “Artist’s Choice”, curated by American painter Amy Sillman. Entitled “The Shape of Shape”, it contains around seventy artworks from the MoMA collection. There is a small figurative painting by African-American painter Romare Bearden, a looming abstract work by Helen Frankenthaler, a sculpture by Duchamp and an oversized relief by Lee Bontecou; artists one wouldn’t necessarily expect to be shown together. Sillman’s curatorial departure point is a research into the role of shape in the history of art. Why, she has asked herself, has shape been relegated to the sidelines as an interest, while colour and line have been foregrounded? Reflecting the fluidity with which Sillman conflates disparate elements in her own paintings, her answer to that question is an eclectic and visually magnetic selection of works that have been placed in constellations on the wall, on small shelves, and on the floor, like loved objects inhabiting every surface of a home.

Sillman’s exhibition acts as a kind of thinking out loud, inviting the visitor to look – really look – and engage with the works in a colour and form-led immersion into what it means to think beyond words. What I find most striking is that, while “The Shape of Shape” is led by formal and aesthetic interests, it also makes space for a sly politics and a quiet wit, which erupt in unexpected places, challenging political correctness and expected ‘meanings’. A photo from Senga Nengudi’s 1977 Performance with ‘Inside/Outside’ becomes an unknowable and haunting image, hung high in a corner above two works stacked above each other on small steps: a Valie Export photo of a razor-shorn line on a hirsute chest, and a small ‘abstract’ painting, Number 40 (1949) by Forrest Bess that, in this juxtaposition, evokes scars and stitches. I recall this sensation later, when I am again standing in the midst of the MoMA’s own selection of its permanent collection, where the isolated presentation of another work by Nengudi, R.S.V.P. I (1970/2003), feels rather tired, its sculptural beauty and political relevance somehow de-activated.

While Sillman’s micro-cosmic world and curatorial experiment is of a different scale than the daunting task of rehanging the entire permanent collection of the MoMA, Sillman’s show is a reminder that risks are necessary to really achieve something curatorially. While most reviewers of the renewed museum have focused on the permanent collection from the 19th and early 20th century, it is noteworthy that their praise has fallen on ‘odd’ juxtapositions, such as the placement of six ceramic vessels by the “mad potter of Biloxi”, George Ohr, next to paintings by Rousseau, Van Gogh, Cassatt, and Gauguin. As well as this strategy of interspersing clusters of well-known works with one lesser-known work, it is also fulfilling as a viewer to be confronted with the sheer scope of one’s own ignorance of historic artists from outside of the dominant narratives. I have this experience visiting the Sur modern: Journeys of Abstraction exhibition, which celebrates MoMA’s recent major acquisition of Latin American art. In one room of the show, a single well-known Mondrian painting, Broadway Boogie Woogie (1942), is unapologetically outnumbered by profoundly engaging works by Latin American artists like Jesús Rafael Soto, Omar Carreño and Carloz Cruz-Diez. This feels like an invitation to learn.

MoMA has promised a regular rotation of works and a complete rehanging of permanent collection galleries on the second, fourth and fifth floors every six months. I will be waiting for Sky Hopinka’s haunting film I’ll Remember You as You Were, Not as What You’ll Become (2016) to emerge from the archives and New York based Laura Ortman to join him, as MoMA makes up for the lack of indigenous artists in the current presentation. I am hoping too that some day Michael Armitage’s powerful and beautifully painted image of male sex workers, Nyali Beach Boys (2016), currently on show at the MoMA in a project exhibition organized by The Studio Museum in Harlem, will stand next to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, making us ask ourselves uneasy questions about cultural power imbalances in the present.

Taking a seat to enjoy the last few minutes before closing time, I strike up a conversation with a New York based artist whose name I didn’t catch. A seasoned MoMA visitor of many decades, she tells me she is bereft by the rehanging of the collection because it has done away with MoMA’s tradition of showing several works by one artist together, which offered insight into how artists think and make work. As she argues, the current showing of almost the entire collection as a string of single works is something that can be done in any regional museum with a small or medium-sized collection. This is food for thought for MoMA’s team as they review the outcomes of this first presentation.