The Lost Moment – Civil Rights, Street Protest and Resistance in Northern Ireland, 1968-69

Gallery of Photography, Dublin

27 September – 4 November

The compacted spaces of the Gallery of Photography, Dublin, make it a challenging building in which to install a major thematically based exhibition, particularly one which relies on the unfolding of a chronologically ordered linear narrative. In the case of The Lost Moment – Civil Rights, Street Protest and Resistance 1968-69 the lower and upper floor galleries have been re-designated as a small museum; becoming a crucible of ghostly history and phantom idealism that continues to haunt the present.

The show was commissioned designed and produced by Gallery of Photography, Dublin in partnership with Nerve Visual Gallery, Derry. Gallery of Photography invited Sean O’ Hagan (best known for his writing on photography for the Guardian and Observer newspapers) to curate an exhibition of his choosing. He suggested The Lost Moment, an evocative title that hints at what might have been had history taken a different turn. The sheer volume of material that has been marshalled and deployed by the curator and his collaborators could easily be overwhelming. However, the authors of The Lost Moment have created the critical ambience and ecosystem in which the concepts and narratives presented may break out and spark off one another, interweaving in the most subtle waves and patterns.

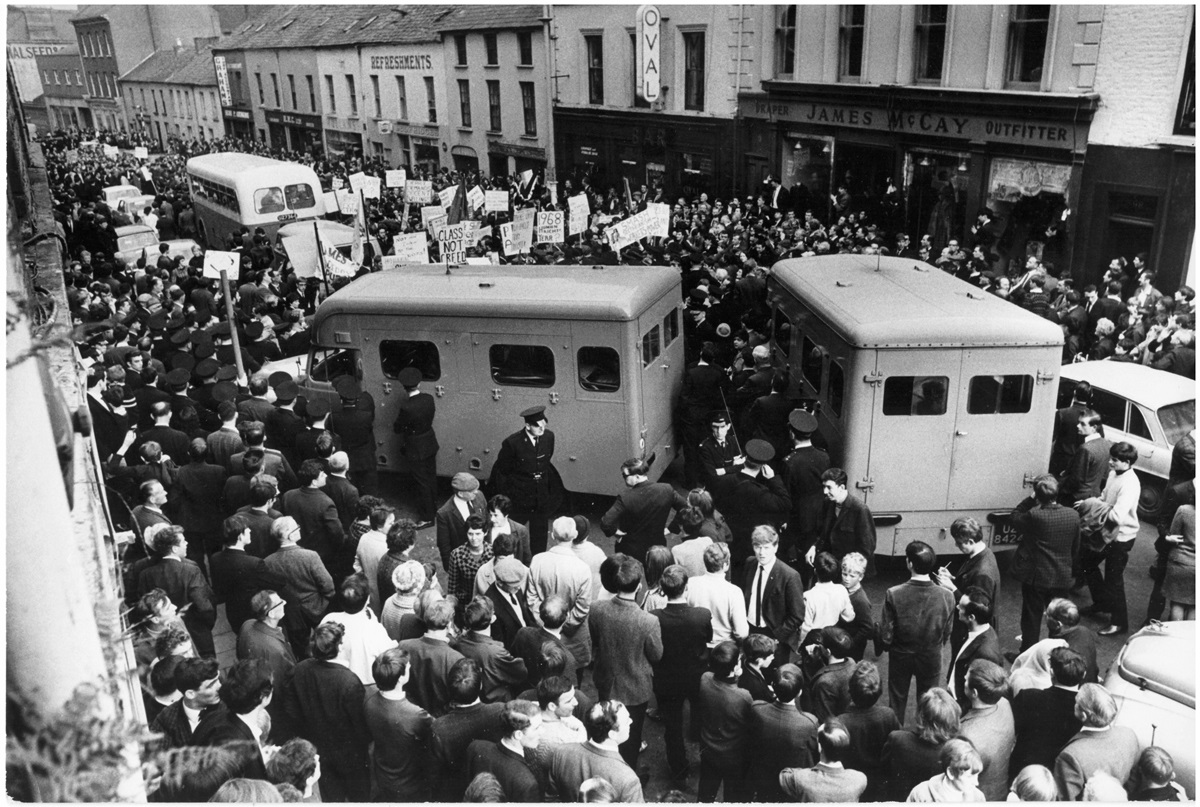

There is a very clear structure to this exhibition. By first setting up the international context – Alabama, Washington, Czechoslovakia, Paris, London, Berlin, Derry and Belfast – the curatorial approach manages to circumscribe and contain this explosive transformation of global politics taking place and push it through the focused period of 1968-69.

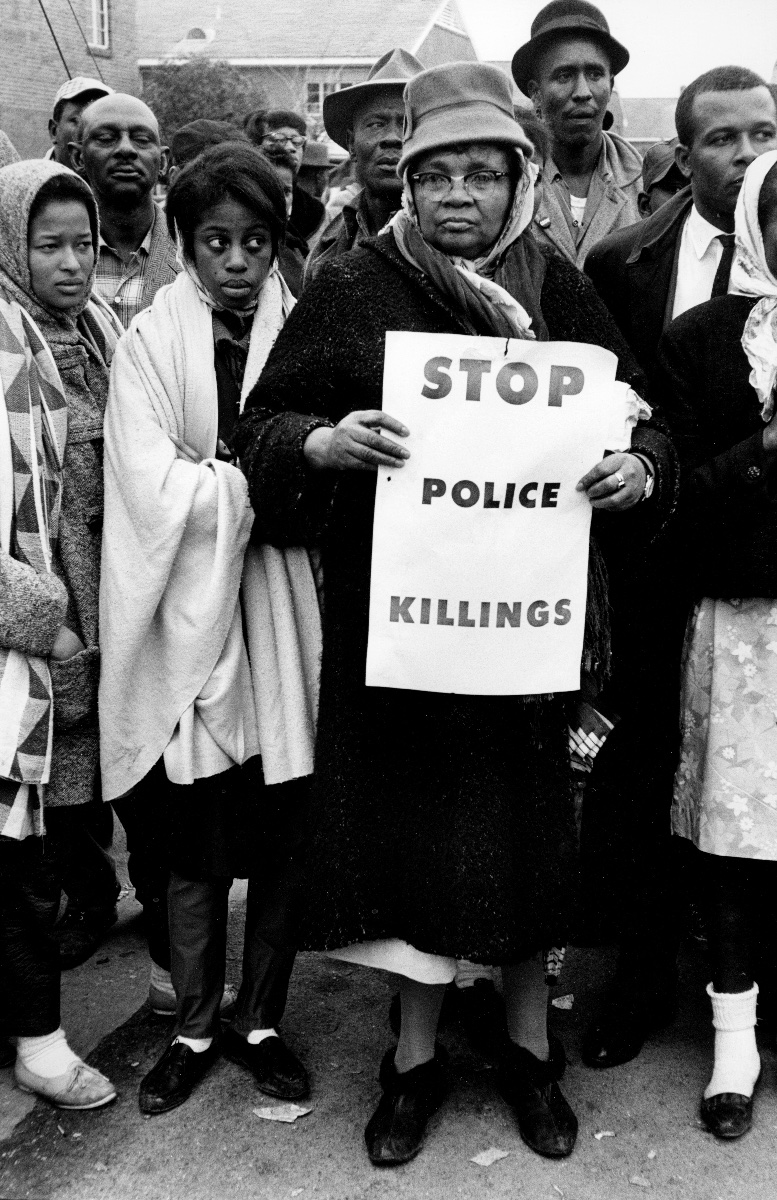

At the entrance to the first floor, the clamour of a multiplicity of voices becomes clear; some conversational and others raised in anger, alarm or panic. We enter a world in turmoil and ferment; an array of footage and photographs, many from celebrated Magnum photographers including Josef Koudelka, Steve Schapiro, David Newell-Smith, David Hurn and Michael Ruetz. Incisive images of disclosure and insight Prague: Invasion ’68, Alabama 1965, The Selma to Montgomery Marches, Paris, May 1968, Vietnam War Demonstration, Grosvenor Square, London, March 1968, and Student Congress, Berlin, February 1968.

Many of these images survey crowds of people and their energetic and purposeful activity, and there are moments when the photographer searches out and reveals an individual presence, a singular participant. For example, Steve Schapiro’s series of images, Selma to Montgomery march, Alabama 1965, includes the image of a nun, her face iridescent, luminescent. Here, Walter Benjamin’s Angelus Novus is invoked; “but there is a storm blowing from Paradise”. Banked in clusters, these canonical images, organised and deployed act as a gateway to the core concern of O’Hagan’s enquiry, the sequence of events leading up to and including the Civil Rights march, October 5th, 1968 in Derry City and its immediate aftermath. Entering this section of the exhibition there are two photographs by Tony McGrath, in which we see the evidence of the poverty and deprivation. It was this institutionalised sectarian discrimination that the working class Nationalist people were forced to endure that led to the formation of organisations like the Derry Housing Action Committee.

Images of a People’s Democracy March from Queens University, Belfast, trace the emergence of Bernadette Devlin as a leading rights campaigner who was eventually elected as an MP to Westminster on the 17th April 1969. American photographer Buzz Logan not only recorded these momentous events on camera but encouraged and assisted individual communities to learn how to do this for themselves. In the centre of this space are four table-top vitrines containing a wealth of printed journals, pamphlets, bulletins and handbills urging people to organise, participate and protest.

In a room off the main space, a sequence of short film segments culled from the RTE archives are projected continuously. Entitled “The Revolution Will be Televised” it contains footage of the Caledon protest, a Queens University student protest, a protest and counter-demonstration in Armagh and perhaps the most compelling sequence, the march shot in Derry on the 5th of October 1968 when the participants were trapped, or kettled, between two police lines on Duke St and violently attacked. We see the moment when Pat Douglas, pressed against police lines, pleads, with arms outstretched “for God’s sake”. He suddenly exclaims, doubles up grimacing in pain as a blow to his stomach is struck from within the wall of RUC men, shipped in from Belfast for the occasion. Clearly, preparations had been made to deal very harshly with this march. It has since been proven that the water canon was brought up to quell the protestors, a measure which had never been used anywhere in the UK before. This is the sequence which circled the global news media and placed the name of Northern Ireland at the top of the international news agenda.

Placed between the first and second floor galleries is another vitrine containing pamphlets, booklets and bulletins emanating from and produced by People’s Democracy emphasising a Marxist analysis and class based politics while organising a network throughout the province.

At the entrance to the upper floor gallery and adjacent rooms a small screen carries excerpts of short and separate interviews with Ian Paisley and Bernadette Devlin who both emerged as leaders and representatives of their communities. In a small room off the walkway and upper gallery is another sequence of documentary footage of the ambush at Burntollet and its aftermath. People’s Democracy had marched from Belfast and had just entered County Derry when the notorious ambush took place; it was the 4th of January 1969, just three months after the police riot in Derry. Images of the marchers, dazed and confused, scattering into the surrounding fields to escape the barrages of missiles and stones, distraught and injured women sob and weep with fear and anger. Michael Farrell tries to calm his comrades with a loud-hailer and to hold the marchers together. The police escort, charged with protecting the marchers, deserted them immediately preceding the ambush and left them to the mercy of a well prepared mob of thugs, some of whom were themselves off-duty RUC men. “No one did as much damage to the Unionist cause as the people who attacked the marchers at Burntollet,” historian Paul Bew reflected later.

Along the walkway in the upper gallery are more photographs of civil strife by Larry Dickinson and an image of a counter demonstration by supporters of Ian Paisley taken by Tom McGrath. There is a reproduction of a cover from the revolutionary left-wing internationalist journal Black Dwarf whose editor, Tariq Ali, is also present in another photograph by David Hurn marching alongside activist and actor Vanessa Redgrave at the Anti-Vietnam War Demonstration in Londons’ Grosvenor Square. Alongside this, there is an image of a Guiness Bottle customised as a Molotov Cocktail poster sized is shown on this issue of “Black Dwarf” along with a quote from Malcolm X:

Revolution is never based on begging somebody for a cup of coffee. Revolutions are never fought by turning the other cheek. Revolutions are never waged by singing ‘we shall overcome’. Revolutions are never based upon that which is begging a corrupt society or a corrupt system to accept us into it.

Stepping back a little from engagement with individual exhibits and the thesis of the exhibition, it is possible to appreciate just how well considered and designed the overall installation is as a walk-through experience. There is space to linger and contemplate. The effectiveness of the material presented is enhanced by a design feature that is repeated at strategic intervals which helps to maintain the mood of sober reflection. Large scale screened montages in dark grey and black act as a backdrop or kind of visual punctuation, and the graphic device of horizontal red bars interrupting these darkened monolithic screens adds to their effect. Like good typesetting, the layout and design of an exhibition such as this is most successful when it is complimentary, but unnoticed.

Also displayed on this upper level are a series of three screenprints, on loan from the CAIN archive, courtesy of Martin Melaugh. Provocative slogans read; The Struggle Continues; With or Without Barricades; The Falls Burns; Malone Road Fiddles; Smash Unionist Junta Stormont; and one image shows a gigantic fist crashing down on the symbol of Unionist power. These graphic images, still trembling with the energy of their inception, carry their message through to our day. Next are some evocative photographs by Barney McMonagle, amongst them a group of children, hunkered down on a street corner, busily filling bottles with petrol; two images of young people being tended to, suffering the effects of CS Gas.

The final room of the exhibition is silent and again we see the device of the dark wall-sized montages used to great effect. On the threshold, a poster sized reproduction from a French newspaper with the caption “Même les enfants participent a la bataille”, is another image of children filling bottles with petrol at the edge of an urban wasteland, a potential battlefield. One of the walls of this room is devoted to the pictures of Gilles Caron. Having just arrived from Prague, he photographed the Battle of the Bogside over a three day period, despite the state and its’ agents having been expelled by the community and a no-go area declared. The words on the gable-end wall became a reality; “You Are Now Entering Free Derry”. The images are a powerful record of organised community resistance to the imposition of oppressive force. The RUC and their paramilitary reserves were repelled repeatedly and failed to reassert their control. These images were published internationally with double page spreads in Paris Match and its Spanish equivalent. It was only in October, some weeks later that through negotiation some military police presence was agreed. The other images that crowd this sombre room are those of Barney McMonagle and Clive Limpkin who worked for a number of British newspapers. The celebrated image of the schoolboy wearing a gas-mask with a petrol bomb in his right hand is from this series of photographs. It has since become more widely known as a massive painted mural on another famous gable-end wall in the Bogside/Creggan. Barney McMonagles’ large format image of a TV reporter set against the backdrop of the urban wasteland and tiny figures masked by clouds of CS gas is memorable demonstrating the significant role the media played in widely publicising the events.

On the end wall there is a small single monitor with a continuous loop of digitized super 8 film showing short clips from between 1968 and 1971. In full colour, the images have a fine saturated quality and unfold silently. A good deal of this footage shows confrontations between groups of young men throwing stones, setting cars and vehicles alight, while ranks of paramilitary police try to curtail their activities. There is also one short sequence, bathed in golden light of what seems to be an outdoor celebration or festival. We see crowds of smiling people, relaxed and happy, being entertained by musicians many of whom were based in the Republic and as a gesture of solidarity performed at the Free Derry festival.

By sifting through the wreckage of the hopes, dreams and fears of this generation who blithely took to the streets as comrades, friends and lovers, setting themselves the task of putting the world to rights, curator Seán O’Hagan has carefully retrieved the enduring evidence of the moment when all was possible and which slipped away so soon. As Eamonn McCann has since remarked “On that day in 1968, we caught a glimpse of how things might be, and that stays with me to this day”.