The Landis Museum

CCA Derry-Londonderry, 26 May – 28 July 2018

Mark Landis donated his forgeries to museums for over twenty years before his exposure in 2010, which characterised him as an art-world fraud. The Landis Museum posits that this is just one aspect of what was at play. For Landis, a man with neither the financial nor the social means to be a philanthropist, the motivation appeared to be as much about the interaction with the institution as his work’s inclusion in the collections. Devised by James N. Hutchinson and first shown at Chapter Thirteen as part of Glasgow International (2018), for this iteration the CCA adds a local annex with four one-day residencies.

The entire exhibition sits on a structure of stained chipboard, which acts as plinth, bench, and stage. Works flow along and around it, blurring boundaries between the diverse practices. Although they aren’t about Mark Landis, his story prompts ideas of subversion and duality, and a certain scrutiny of material.

Curator of The Landis Museum, James N. Hutchinson presents a video Proposal for a Collection showing Mark Landis producing a copy of Charles Courtney Curran’s Three Women. In his cluttered home, books stacked inaccessibly on every surface, we see him work over a photocopy of the original, using the ‘wrong’ materials – coloured pencils, marker pens. He works quickly, perched on a bed surrounded by cultural references and stimuli. An important inclusion, this video work allows us to consider Landis, and what he exposes about art institutions, on a level with the other artists and with conceptual or postmodern concerns. The final painting by Landis is also displayed, with white gloves to inspect its integrity.

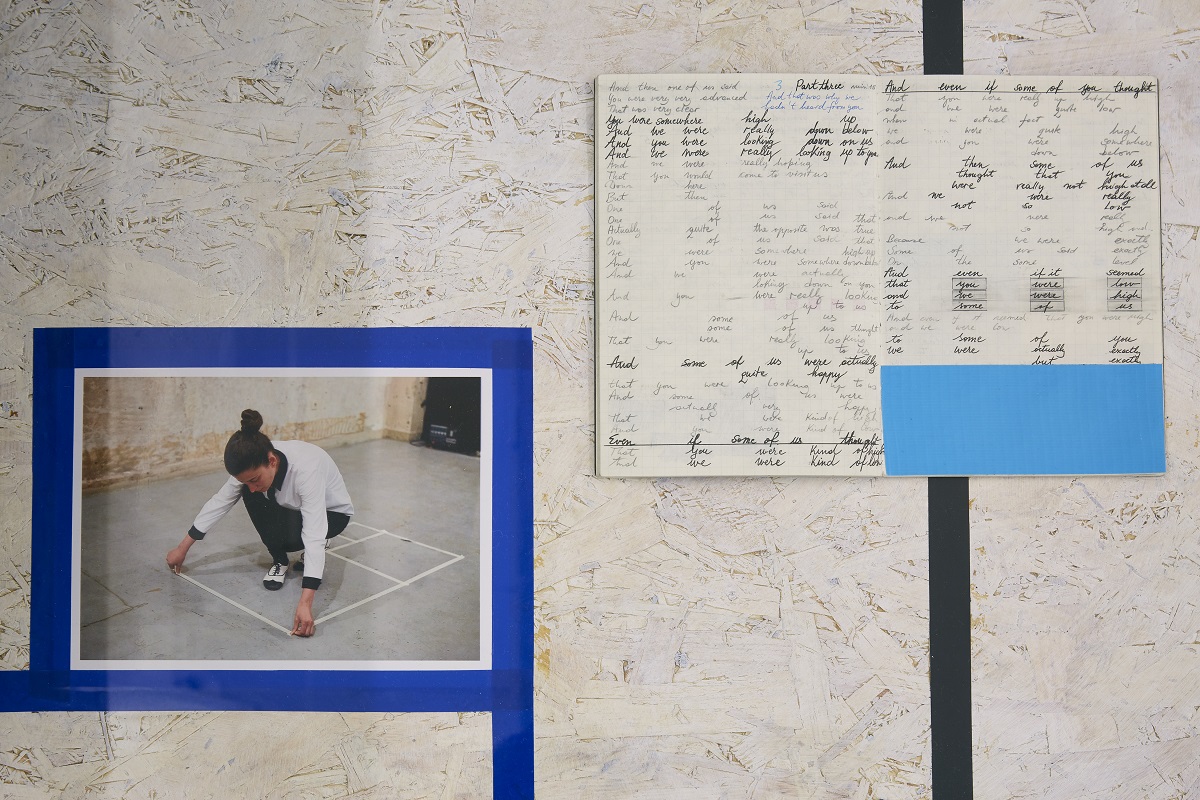

In Sarah Pierce’s Lost Illusions/Illusions Perdues, Landis is contextualised in relation to Balzac’s lead character in Illusions Perdues, who struggles to replicate the manners of cosmopolitan Paris. In the double screen video work, we see two students perform exercises based on Brecht’s learning plays, wrestling with gesture and articulation. They embody the process of art-making, a process involving duality and negotiation. Irina Gheorghe’s evolving work Foreign Language for Beginners, speculates on how we might speak to aliens at a point of first encounter. Notes from her performance remain on display, reminiscent of concrete poetry, or repetitive instructions of computer code. I found myself coming back frequently, the back and forth of positions acting as a sort of palate cleanser.

And we were really

not so low

and we were really not so high and

Because we were exactly

Some of us said exactly

On the same level

In many works a residue stood in for some unrepresentable past action, or a transformation point, and conjured a visceral kind of trajectory. For instance in Alexandra Sukhareva’s sculpture Trap, two fibreglass tubes resembling brittle sheets of rolled glue, embedded with unidentified small grains, were created as a device to contain the disease of her sick friend, the act of creation also a means of solace for her. Now he is well again, it exists in an exhausted state, an extinct talisman. Similarly, Alex Impey’s small objects imply a direction of travel. They’re constructed from industrial materials with the aesthetic of something functional, but with the function removed.

A series of appealingly tactile sculptures sit along a narrow shelf. There’s a raw clay sphere (which I choose to believe is hollow) on three stumpy legs, a red circle of felt with blue beads, a matt-smooth terracotta brick, and a shiny brass disc with indented centre, and edges bent into a cymbal-stetson. Like part of an ethnographic collection, or icons to communicate with Gheorghe’s aliens, they were produced by Kapwani Kiwanga as abstractions of objects from Berlin’s Dahlem Museum. Now removed from their referents, it’s impossible not to seek something of the unknown original in their surface. In another work by Kiwanga, this time a video piece The Secretary’s Suite, she mines the surface of a black and white photograph. Ostensibly a study into diplomatic gift-giving, she presents a mesmerizing stream of documents and astonishing links between artefacts and events, with an authoritative voiceover dropping just the smallest seeds of doubt and conspiracy, which go on to pervade the rest of the exhibition.

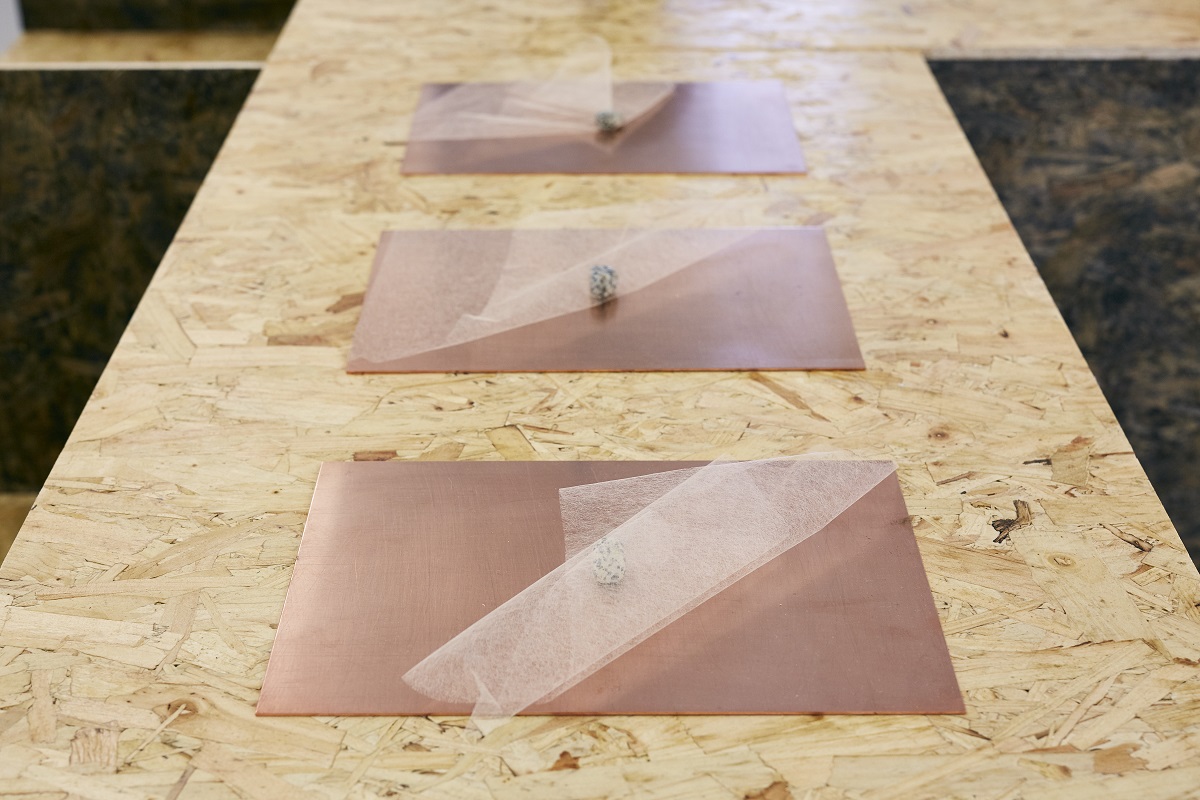

Nina Liebenberg undertakes a similarly rigorous object analysis, with her audio description of a medicine box, held in collections at the University of Cape Town. Liebenberg’s report from within the institution acts as instructions for The Landis Museum’s curator to make a drawing. This is also displayed, stripped of the political connotations of its referent. Bianca Baldi presents a length of beads arranged in a waveform, which those who have visited archives will recognise as the weighted ropes used to hold pages flat. The beads are jasper stones, covered in black fabric. Titled Snakeweight, the sculpture is an elegant transformation of this object and the muscle memory of its weight, into a talisman. Just above this in Insufflage, jasper stones on copper printing plates, with each stone pinning down a sheet of tengu paper, the lightest of papers – so light it resists the print implied by the copper. As exemplified by Baldi and Liebenberg, objects are transformed in this exhibition, they say something about things that aren’t there, through materials or the process by which they are formed.

Positioned throughout the exhibition are four small papier-maché busts, worked to the point that they are distinct from one another, but unfinished. These were made by James N. Hutchinson’s mother while undergoing chemotherapy, using a newspaper her son picked up in Hong Kong, containing Edward Snowden’s shocking revelations. The same material was used by two people for two purposes: Snowden for its political function, the paper simply a vehicle for his content; Jill Hutchinson generating new meanings from the pure physical material. The artist acts as middleman, bringing the material from a city where Snowden was hiding to his mother. The work remains frozen at this point of encounter, with Snowden’s status as a citizen and symbol unresolved, and with the death of the artist’s mother before finishing the pieces. This provided a profound encounter, with a touch as light as Baldi’s tengu paper.

The adjacent space hosts the local annex, a series of residencies responding to the exhibition, with remnants of live ‘public moments’ on display. Phillip McCrilly left behind a jar of sauerkraut, apparently made using salt mined from fields around Robert Smithson’s 1970 work, Spiral Jetty. Helena Hamilton conducted a ‘post-digital’ experiment into chalk, referencing the language of computer coding to explore the properties of this simple writing material. While browsing the Rijksstudio, Dorothy Hunter talked about the privileging of the surface, and the ‘hack appeal’ of institutional spaces of the art world, leaving behind an annotated postcard publication with brief lines forming abstract titles or broken contextual links. As I write, Katrina Sheena Smyth leads a mediation workshop, and refers to materialism and encounters with the absurd through The Pataphysics of Ghosts, an essay by the surrealist René Daumal. Hunter’s was perhaps the most direct response, neatly reflecting on the aura and individualism of Landis’ practice. Other responses resonated through transforming and interrogating substances, and echoed the liminal spaces of the main exhibition.

In The Landis Museum, Landis’ story is pulled in numerous directions, where objects seem loaded with endless implications and unknown forces produce unexpected meanings. At times I found the complexity of works off-balance, but overall the project produces something greater than the sum of its parts. Directly or indirectly, the various works contextualise Mark Landis in a way that left me pleasantly wrong-footed, questioning the values ascribed to art and the process of its making. Hutchinson’s light touch focused enquiry into the duality and trajectory of the works rather than finished pieces. The artists act, manipulate, imitate, and invent; The Landis Museum spins uncertainties while highlighting traces, and transformations of objects and their meanings.