As part of the fourth IMMA Screen, the online screening of film and video from the museum’s collection, two works by Isabel Nolan are presented on the website: Sloganeering 1-4 (2001) and The Condition of Emptiness (2007), alongside an interview with the artist and additional audio archival material. This restaging of Isabel Nolan’s work resonates with our isolation under lockdown, if only because of the coincidence of timing. But behind the accidental relevance lies a startling exploration of repetition and variation, boredom, disillusionment and the limits of identity.

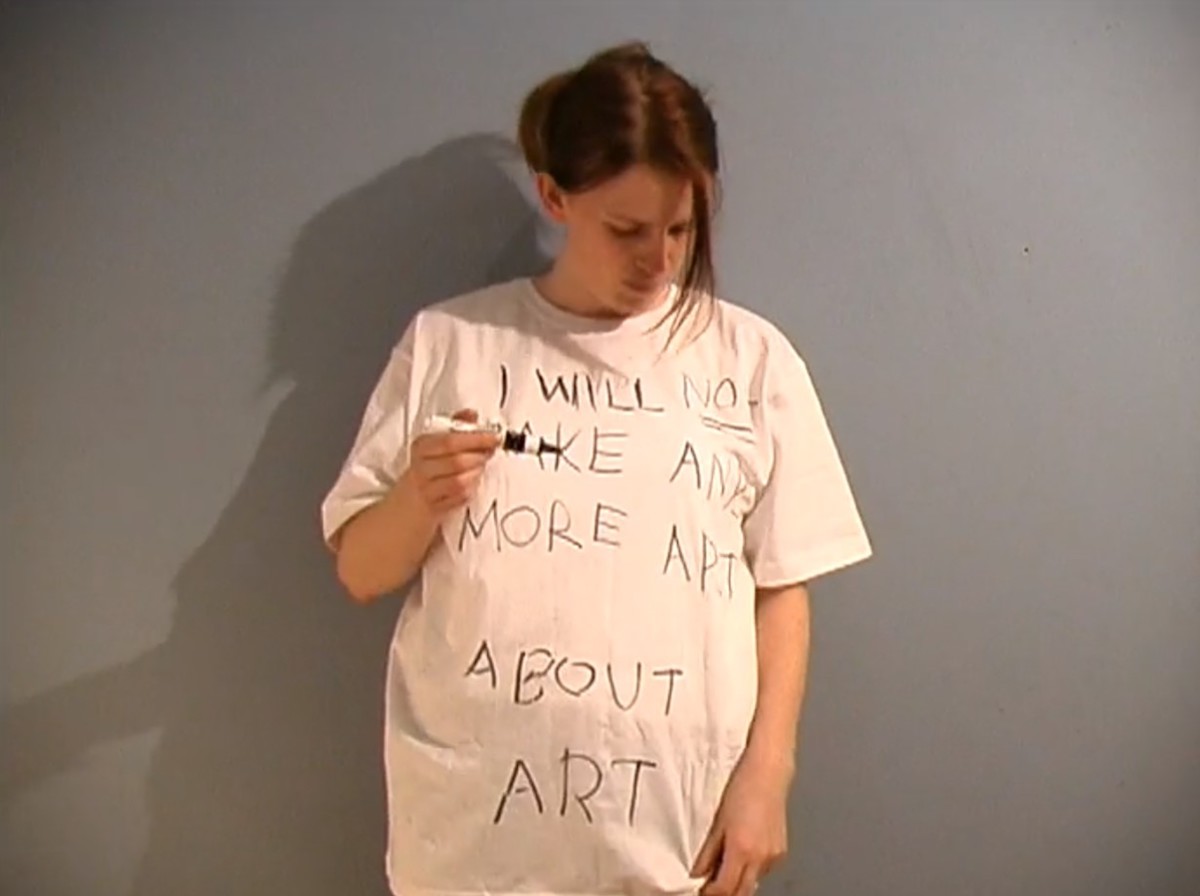

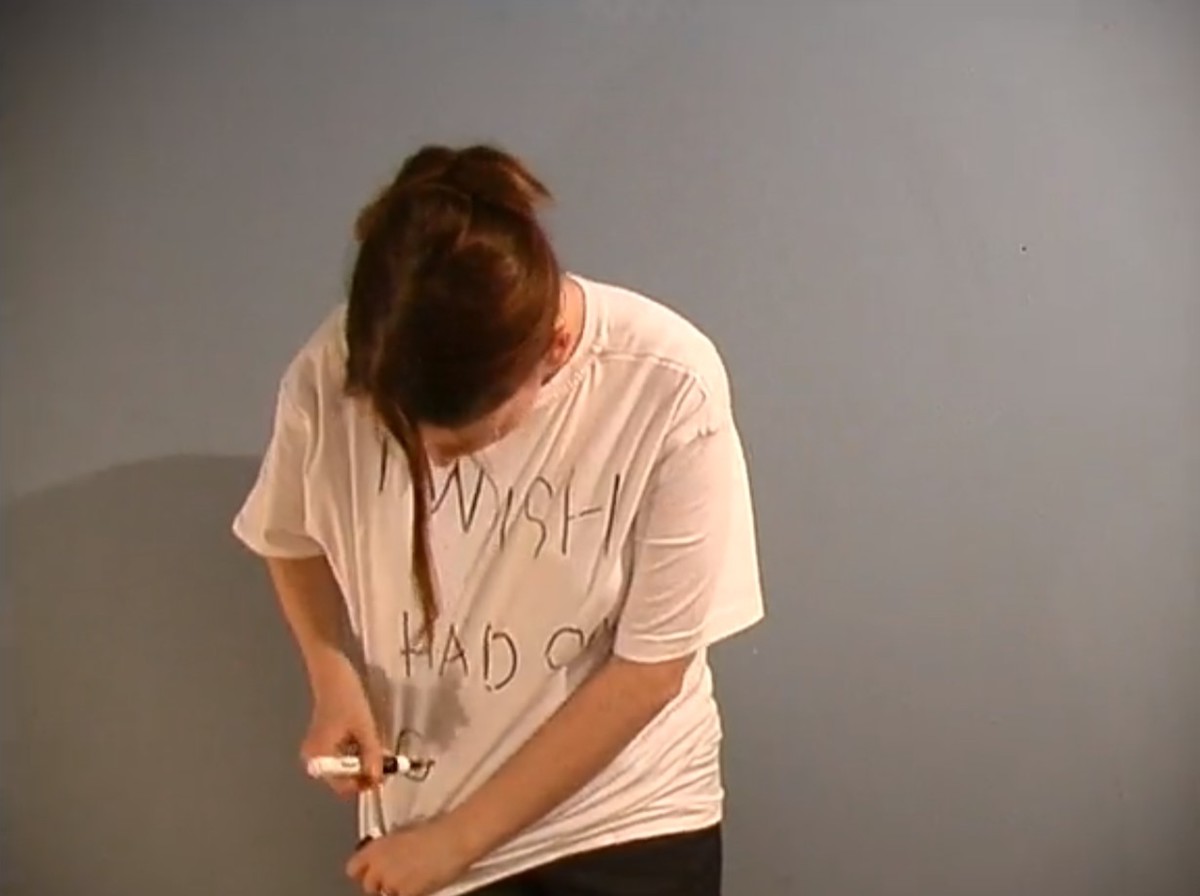

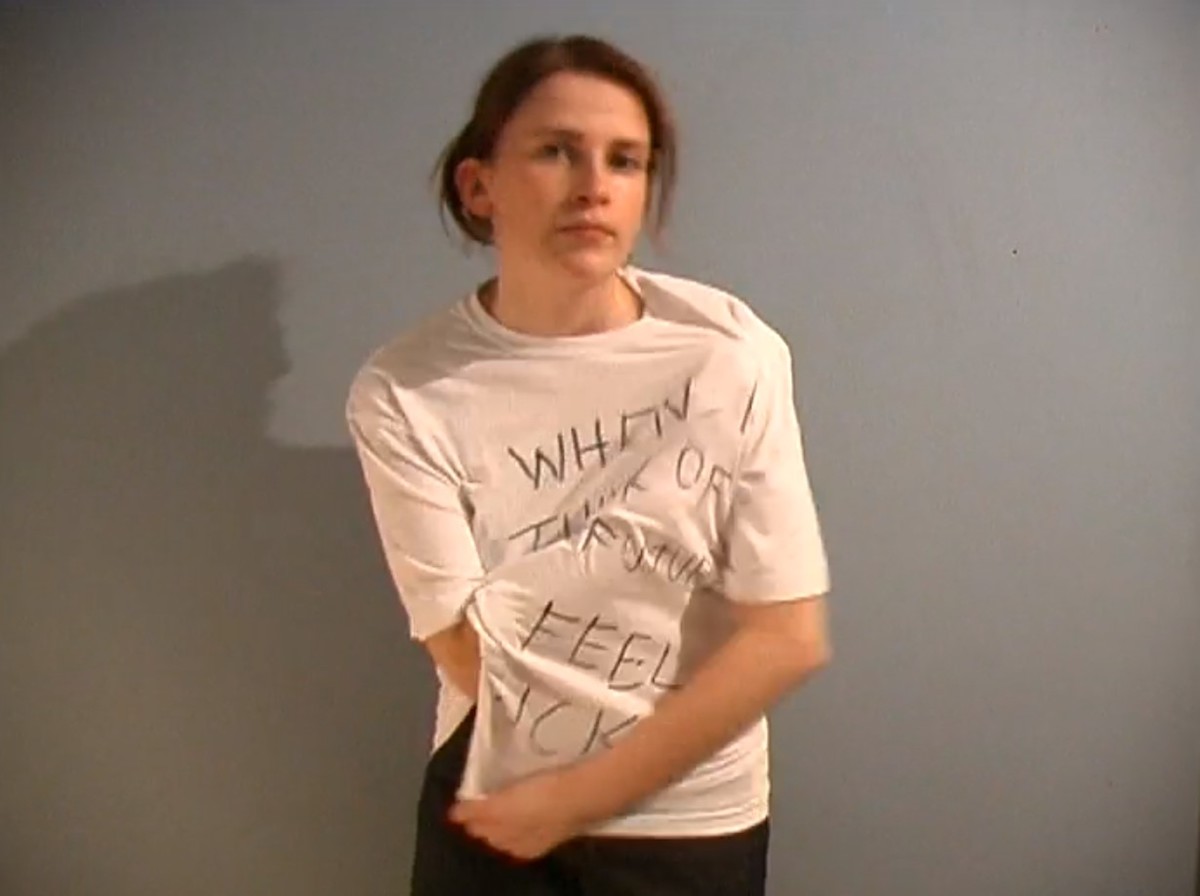

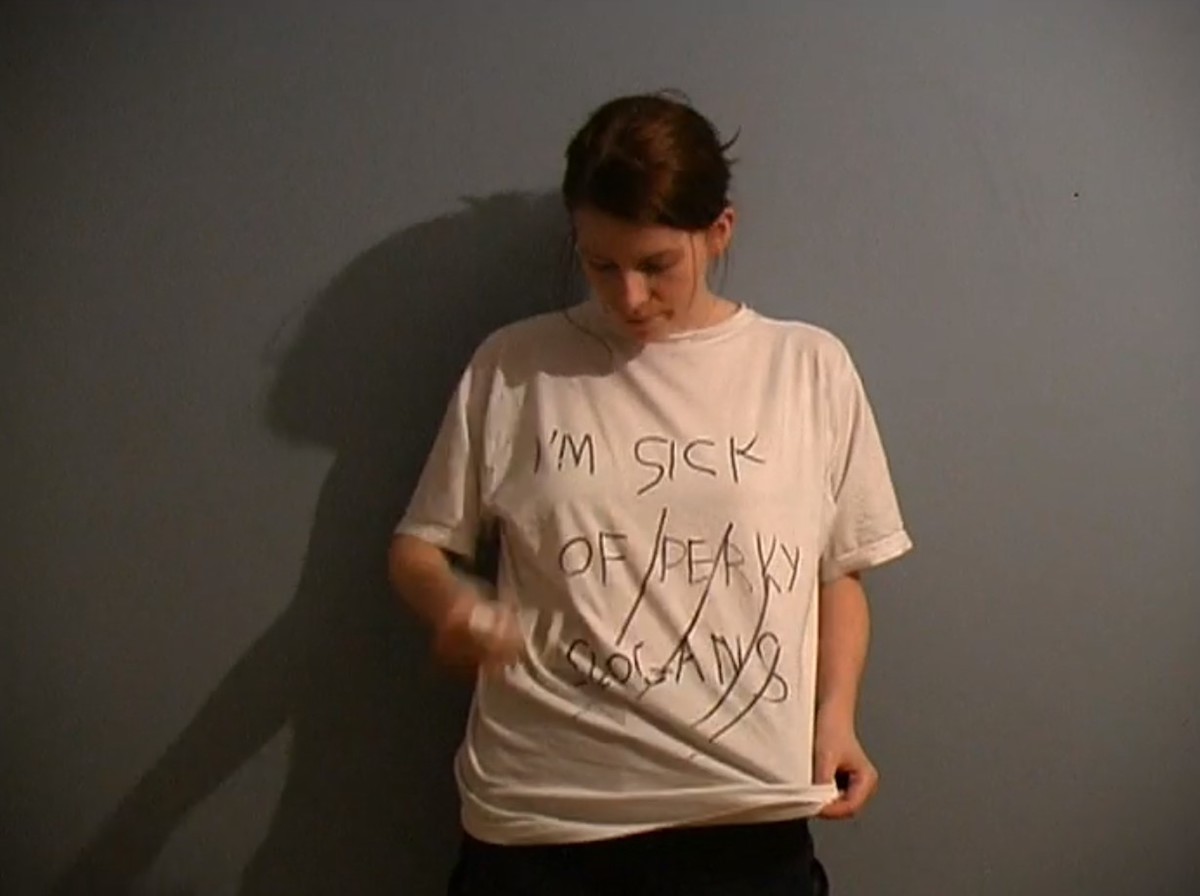

Nolan made Sloganeering 1-4 in 2001, as part of her installations Once Upon a Time and How Things Turn Out at IMMA in 2002. In the four minute video, we see a fairly nondescript scene: a woman is wearing an off-white cream t-shirt against a plain grey backdrop. Over the course of the short video she writes on the t-shirt. The movement is sped up; when there isn’t much room left she’ll turn the t-shirt around to keep writing. The phrases range from revealing personal anxieties (“When I think of the future I feel sick”) to self referential gestures (“I will not make any more art about art”), always expressed in colloquial soundbites. As the video continues, the tension builds with the phrases becoming more dramatic and often crossed out, scribbled or obscured with drawings of shapes. At the end we reach the climactic conclusion: “I’m sick of perky slogans.”

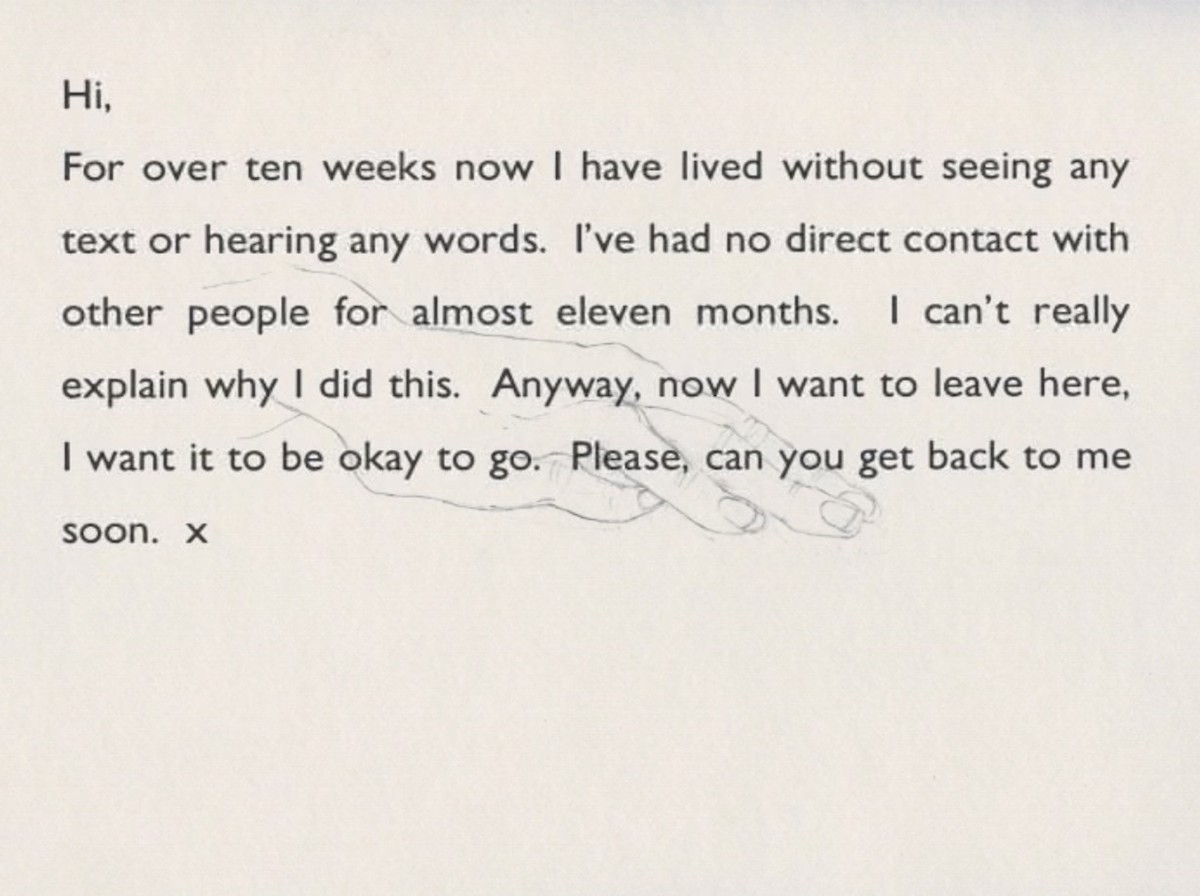

The Condition of Emptiness (2007) is often misinterpreted as an autobiographical work due to its heavy usage of the first person perspective, Nolan explained in the interview with Christina Kennedy, the Head of Collections at IMMA. In this animation, a pencil drawing of a tree fades against a trippy psychedelic palette until it becomes a blinding white light; eventually the scene shifts, to be replaced with a simple drawing of a hand which is overlaid with text. An extraordinary story unfolds about someone who, for ten weeks, has tried to avoid all external stimuli, including other people, any TV or books and even removing words from the toilet seat. The opening message reads: “I can’t really explain why I did this.” But now they have doubts it seems, explaining: “Anyway, now I want to leave here, I want it to be okay to go. Please, can you get back to me soon. x” The exact relationship between the protagonist and who they’re communicating with remains unclear, adding to the many layers of its eerie, perplexing narrative.

Both Sloganeering and Conditions perform the tensions between the self and the wider world. But rather than reach out, the protagonist has tried to turn inwards. Nolan connects this fantasy of retreat with the idea of the artist being removed from society, offering a perspective informed by their outsider status; she also calls this ideal ‘nonsense’. In part she’s addressing a long-standing question about the creative life: to what extent artists are understood as part of and shaped by the world they live in. But this work has also gained a new relevance.

The conditions of lockdown, a heightened sense of isolation and separation, come easily as a context here for the works, especially for The Condition of Emptiness. A story about avoiding contact invites an obvious parallel in the middle of a pandemic. What the videos share is a preoccupation with identity, often using and reusing cliched language and borrowed phrasing. There is a frustration with the limits of our capacity to express that identity too. Can being alone offer a kind of freedom? Or, perhaps, we lose ourselves when isolated; being with others shapes us into who we are. These are the kinds of concerns – deeply felt, existential dread and hope – that preoccupy artists endlessly. But the sense of relevancy these works evoke during lockdown gets in the way of this conversation, as we focus on the specifics of the day we cut short the larger, timeless potential of the work.

The pandemic has weighed heavy on the perspective of artists, audiences and everyone in between, colouring our experience of culture. A certain cycle has unfolded during lockdown on the review pages of art magazines. Critics lamented the shutting of galleries and museums, wrangled with the explosion of digital alternatives and now relish the materiality of physical space as shows reopened and launched in September. There’s been a glut of art that was delayed and even newly produced in response to this also: I am now getting a lot of press releases about exhibitions of work made during lockdown; or the return of shows that were cancelled; and, more generally, artists’ practice framed and contextualised within recent events.

While Nolan’s work may invite a connection to lockdown, it is also an argument against such a simplistic interpretation. Known for painting, sculpture, text and video, her broad ranging practice is defined as much by a certain materiality and stylistic play as it is for how such works are ambiguously dense with meaning and metaphor. Far from clarifying anything, each point of reference unravels ever more narrative potential. Sloganeering, too, would have much to offer as we head into another US election cycle, but something is lost in translation if we frame the works in this way. Nolan’s art is an argument against such easy readings.