Everything Disappears was shot in 2014 by Irish artist Kevin Gaffney. Set in the capital city of Taiwan, Teipi, the piece follows four locals, Revanshu, William Hsu, Lucie Chen & Issac Tsai, across seven surreal, staged and revealing episodic scenes as an exploration of fluid identities and queer experience overlapping with national identity, gender roles, racial stereotypes and mental health. This artwork was originally exhibited as part of the residency in Taiwan in which it was produced, entering the IMMA permanent collection shortly after. Audiences will have the opportunity to experience it for the first time since being acquired as part of the online IMMA Screen programme, a partial response to lockdown.

IMMA Screen offers a kind of material history of art on the island of Ireland. The institution started collecting artists’ film and video in 1991, signalling a shift towards Irish film practice being taken more seriously by both curators and artists alike. It is today undertaking a major process of digitising the analogue formats such as VHS tape and Laserdisc so they can be better preserved and displayed into the future. But this material history also offers an insight into artistic practice. There is a world of difference, for example, between Vivienne Dick’s punk embrace of countercultural filmmaking (previously exhibited as part of IMMA Screen) and Kevin Gaffney’s research-led and Arts Council funded high production investigation of identity and lived experience. They share film as a medium, as well as a politically charged desire to push back against clichés and stereotypes, but enter artistic discourses shaped by radically different histories and economies. This programme also offers an invaluable insight into the lives and careers of the individual artists.

Graduating from the Royal College of Art’s MA Photography & Moving Image in 2011, Kevin Gaffney is an Irish artist and current PhD researcher at Ulster University. In conversation with writer and curator Sara Greavu, Gaffney describes seeing early seeds in Everything Disappears for his approach and ideas which have developed over the following years; in short, a playful and surreal blending of fact and fiction which explores questions of queer experience, history and representation in relation to the state and national identity.[1] In his monographic essay, Caoimhín Mac Giolla Léith drew attention to this particular period in Gaffney’s evolving oeuvre. From 2014 to 2016, this period is bookended by two longer, more adventurous films: Everything Disappears in 2014, and “his arguably most spectacular film, A Numbness in the Mouth” in 2016.[2]

If A Numbness in the Mouth represents a kind of pinnacle in Gaffney’s career thus far, as the artist implies and Mac Giolla Léith argues explicitly, Everything Disappears traces the conceptual and formal roots which led to that point. Focusing on four local participants sourced through an open call from the residency’s Facebook page – the artist uses the term participant here very intentionally – the project began in the National Library of Ireland with colonial accounts of Taiwan, highlighting how research can only go so far. He knew the work had to be opened up to others’ live experiences. While the research addresses and explores ethical questions central to lens-based practice, it also brought on formal advancements for Gaffney. Previous works had largely been silent and often featured the artist himself in a number of guises, and this silence, Gaffney explained to Greavu, felt ‘tepid’.

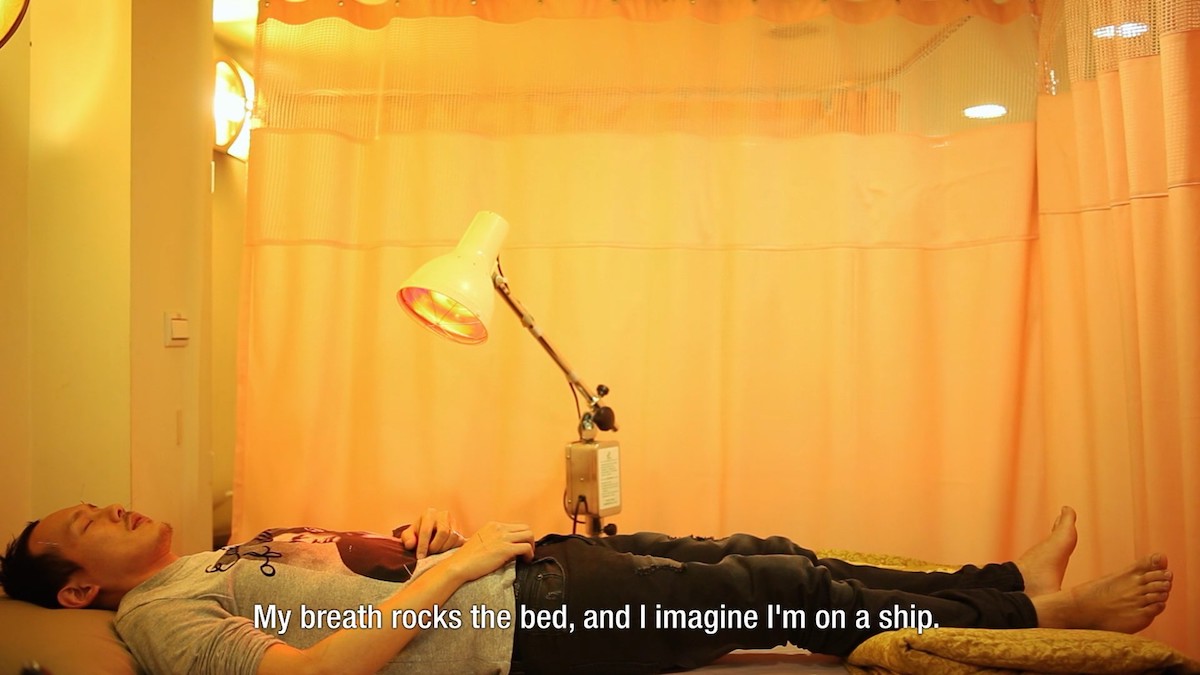

The research informed the process and became a point of departure for it as Gaffney began experimenting with automatic writing, inspiring much of the strange, dreamlike dialogue which defines the work. The characters’ conversation is unnatural and highly staged, often using beguiling metaphors (“Nothing is worse than a wet heart”)[3]. And now with actors, or rather, a cast other than Gaffney to lead, the artist could weave together absurdist scenes and personal accounts of queer experience in Taiwan, blending historical contexts and fictional elaboration. One scene of a man throwing plastic balls at a woman as they make their way to an ‘absurd’ ball pit in an 80s-styled school gym is directly from a nightmare the actor experienced during the shooting. A fifth participant, who unlike the others is unseen, describes having to ‘perform’ their mental health issues for bureaucrats to avoid military conscription. The abstract narrative devices mixed with the personal accounts bring an emotional core to enliven what could otherwise be presenting clinical research on a screen.

If there is a constant to Gaffney’s ever evolving practice, it is a politically curious and narratively ambitious interrogation of the history of queer experience in the shadow of the state. It’s easy to see why A Numbness in the Mouth can be seen as a high point for Gaffney. The film looks to a hotspot of Irish history, telling the story of a flour mill which exported food during the famine and was an active participant in the 1913 lockout of Irish workers, adding a speculative narrative centred on queer identity and climate change. Coinciding with the 1916 centenary, this was an Irish artist addressing the weightiest moment of national reflection through a confidently contemporary argument – with the crew and equipment, thanks to the funding of a Sky Arts award, to really pull it off. In 2020, Gaffney is set to continue this trajectory in a new commission at Crawford Gallery called Expulsion – his longest film to date – which imagines the gallery as the seat of power for an imagined queer state, taking a critical view of how quickly such a country could become distorted by the trappings of power, status and bureaucracy.[4] As Expulsion will have neither the budget or centenary as context which leant A Numbness in the Mouth such momentum, it will have to find a sense of significance elsewhere. In his conversation with Greavu, this doesn’t seem to be a problem for Gaffney. Much of his process relates to how Everything Disappears happened, but now the script is tighter and the shooting schedule is meticulously planned. He describes the sense of collaboration from working closely alongside just two actors, and jokes about the problems which will arise as he steps in to be his own crew. Shooting in Crawford, he describes how a smaller set and closer relationship with the cast brings a sense of openness; a kind of return to Everything Disappears. “It felt good to make it like that.”[5]