Circa is delighted to present another instalment from our collaborative ‘Archive Project Editor’ award. The commissioning editor is Bangkok-based Dr. Brian Curtin whose project, titled Travelling South, In Theory, supports cultural workers based in South and Southeast Asia to engage with Circa’s archive. Full details of the project are available here.

Below Thái Hà pens an experimental, deeply thoughtful, text about language, translation, and opacity as the means by which artworks can be engaged across time and different cultural contexts. Prompted by a video installation by Susan MacWilliam, Hà is interested in a politics of mutation for the practices of interpretation and representation. Here the inherited language for framing contemporary art may be rendered anew, or different from its typical forms.

Thái Hà: A Letter to Susan MacWilliam

I am opening Did you mishear me misspeak? with a flawed premise: to look to language and translation for possibilities of speculation, dreaming, improvisation and play, all while expressing frustration at the limitations of language in its very preface. Specifically, my project examines the language that we have inherited from postcolonial studies that is still circulating today both in academic and mainstream discourse, even though, as I would contend, it is no longer sufficient to describe our experiences.

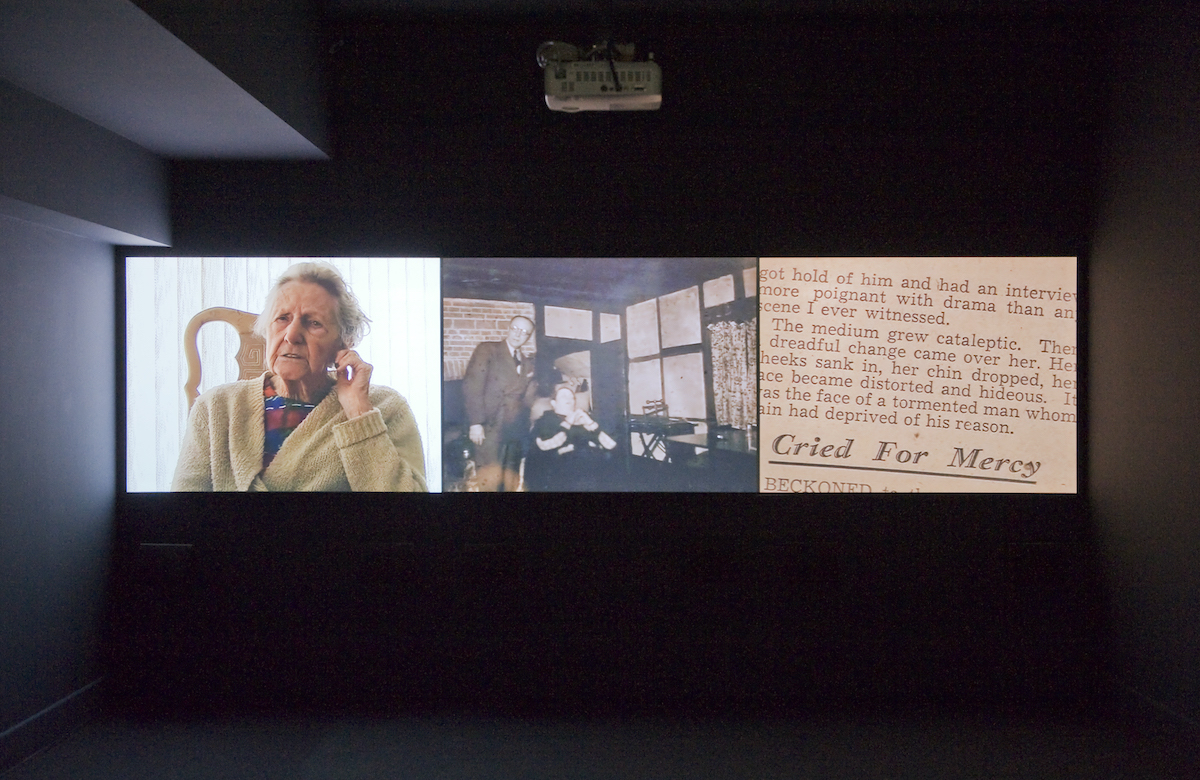

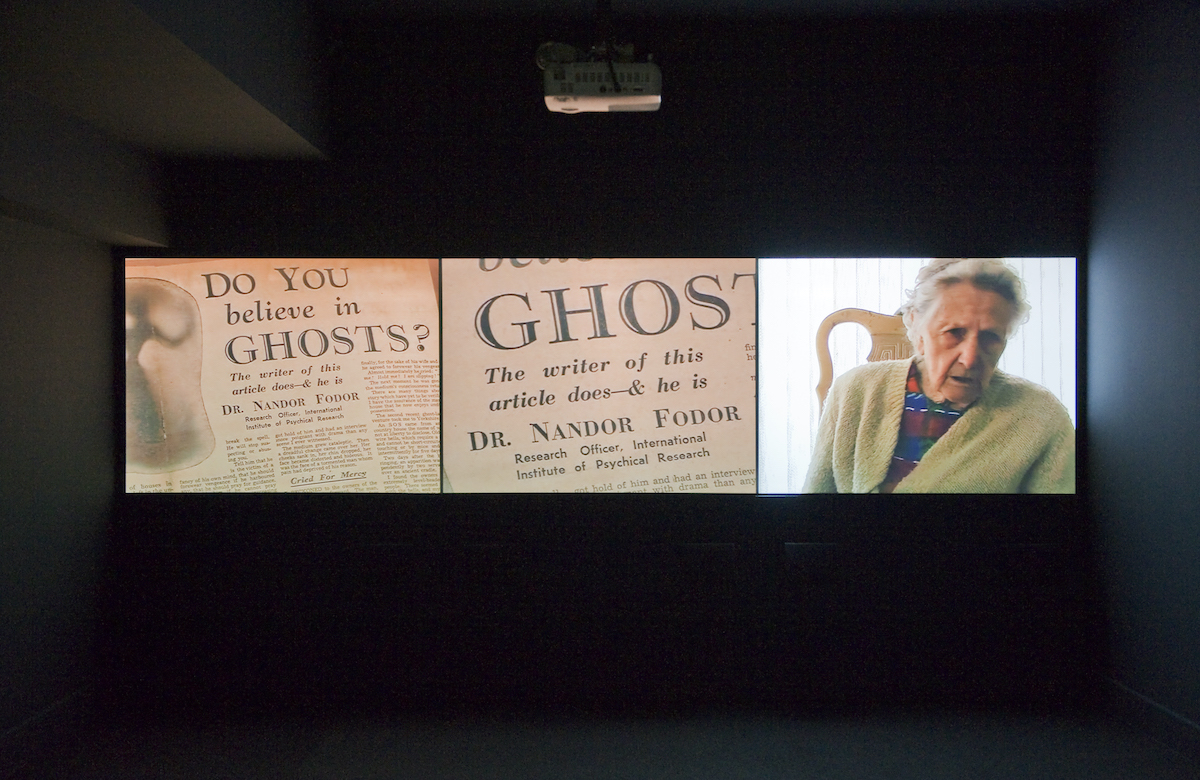

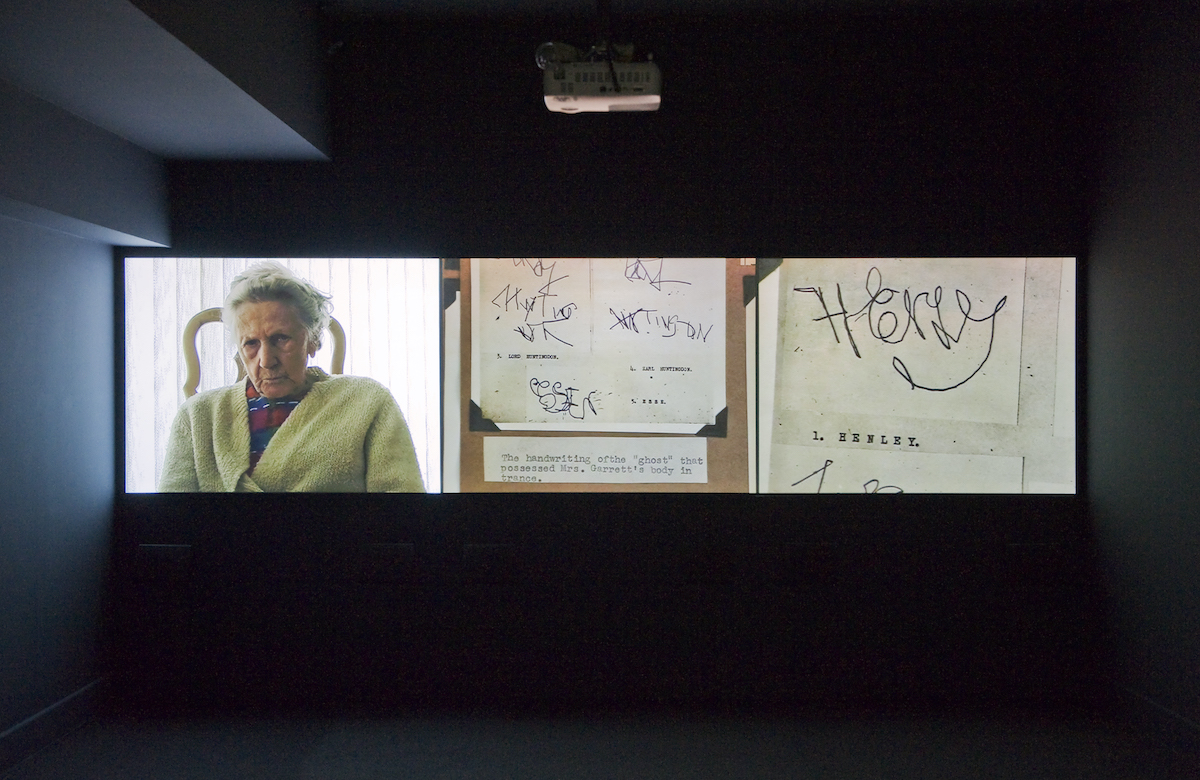

This essay is a letter to Northern Irish artist Susan MacWilliam. I have chosen to write a letter because some of my frustrations with language are very much spill-over from fatigue with the essay form: it is unsatisfactory for me to talk about artworks, when the form of what I write rarely mirrors what I experience. Born in troubled Belfast in 1969, MacWilliam’s work considers the world of the paranormal and super-sensory. My letter responds to the work titled Eileen (2008), a three-channel video installation in which the artist conjures up Eileen J. Garrett, hailed as the world’s greatest medium, through the annecdotes and gestures of her daughter Eileen and granddaughter Lisette. In particular, I explore how the craft and communications of a medium can be known only to herself, and in speaking of her life, her daughter and granddaughter partly recalls, and partly deciphers how she did her “psychic thing”.[1]

Like the cuckoo song I discuss below, I am approaching this project as a weaving of lyrics from the Circa archive, the works of artists whose formal qualities inform my own writing style for each written project, and my own understanding of language that spans the three I speak, and the translations that I constantly negotiate between those language-cultures.

*

Dear Susan,

These past days I find it hard to sleep. I try counting sheep but in my hoarse voice numbers turn into gravel. I swallow the stones but in their numbers I cannot rid them from my vocal tract.

I have not spoken in days. Words as stones heave out of my stomach only to get lodged again; in my throat they clack against each other as if sounding out a knot of sparrows. The smooth grey masses sit so heavy I cannot let them out with air, their denseness like black holes that dull the ring of what I utter.

I asked if you had misheard me, though maybe I had misspoken. I remember what Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak wrote about speaking, to see who’s speaking, who for, and if the spoken for can really speak.[2] Though concerned with the who, I wonder if her preoccupations are more about the voicing of language. Under the category of subaltern, defined by its inherent exclusion, and if the micrological textures of power prevent the subaltern from possibilities of speech, the question of who’s speaking, then, necessarily shifts the focus to agents who can actively speak – or specifically in Spivak’s critique, the Western intellectual elite.[3] The subaltern is never engaged with as it is, only through the prism of its relationship to the Western subject. If the subaltern speaks and is heard, which is more impossible still, it must do so in the very language that has excluded it, that of the dominant culture of the West.[4] To use this language to speak is to remain “entrapped in a closed loop […] that [limits] our current conversation[s] and actions.”[5] Again the stones choke me and again I swallow them. They reach the depths of my bowels only to wedge at the folds.

I cannot sleep, the stones make me ache. I cannot speak this language well when there’s my own I’m learning to voice – a language that mutates at the moment of speech, where the spoken and unspoken do not signify so much as translate – a mutation further still.[6] Mutative speech eludes understanding, an impulse for transparency that dissects other cultures to reduce them to their flayed parts. Learning to speak mutations, I take on an opacity that, according to Édouard Glissant, “is […] subsistence within an irreducible singularity. Opacities can coexist and converge, weaving fabrics. To understand these truly one must focus on the texture of the weave and not on the nature of its components.”[7] I pause at the texture of the weave and am reminded of Sean Bonney’s “cuckoo song”, the lyrical tapestry “in which the lyric ‘I’ loses its privatised being, and instead becomes a collective, and oppositional collective, spreading backwards and forwards through known and unknown time.”[8] In mutative language, the texture of the weave implicates linguistic practices that cannot be grasped through a structural breakdown of its phonemes, morphemes, syntax. It is perhaps moments of improvisation and ad-libbing that, for the opaque listener able to conceive of the opacity of the speaker, creates complicity.[9] The listener does not grasp me, but in a moment in time she inhabits the textures of what I say beyond what I say.

Complicity is not solidarity. Opacity eludes understanding. Solidarity through alliance requires an understanding among the allied of the similarities in their conditions that helps them “become” the other – a suspension of opacity.[10] Intrinsic to Bonney’s cuckoo song, however, is the notion of opposition within the collective, the push-and-pull between one’s own lyrics and the fragments of others’ songs. That the parts are sung together is not a given. Perhaps the singer herself is not aware of what she will lift from the lyrical archive until the moment of singing. The lyrics’ being-in the-world hinges on time. At the moment of singing, it forms part of a new song; in the mesh of past and present lyrics, as per Glissant, opacities converge.[11] Each lyric conceives of the other’s opacity in acquiescing to the newness and none-newness of its own being in the history of song.

I think you had misheard me, but I also had misspoken; which is to say, from where I imagine you are and from where I imagine I am, the rate at which our languages mutate makes it impossible for one of us to simply speak and the other to be able to hear. But I can attempt a translation of myself that does not represent me and instead expresses my opacity.[12] Translation is an echo; it cannot signify the thing it translates, nor should it strive to “discover what lies at the bottom of natures.” [13] It gladly assumes mutations or rather it is a practice that relies on mutations – misunderstandings – to proliferate.[14] I could attempt a translation of you but in the end it is only of me. Opacities can only converge.

The stones sit still inside of me. They are dense and I am uncomfortable. But I like the sparrow sound I make now when I open my mouth to speak.

Yours in clacks,

Writer