Ahead of the opening weekend of the 38th edition of EVA International, Inti Guerrero discusses his curatorial concept, shaped by an early engagement with the painting Night’s Candles Are Burnt Out (1928-29) by Irish artist Seán Keating, in a conversation with Sharon Phelan.

Hi Inti, I’d like to start by asking you about your background as a curator. What drew you towards a curatorial practice, and what is it about the medium that most interests you?

I went to art school, but it was an art school with a semester where we were given a class in curating. It was an invitation to understand the exhibition as yet another medium, in the sense that, as with painting, installation, and video making, the exhibition itself could become a creative medium. If you think about it in that way, perhaps the closest existing medium in the arts that one could identify, or relate to that notion, is collage. When you think of collage, you see the reminiscence of autonomous objects; you see the composition that they create together that juxtaposes languages and forms narratives. Somehow, that understanding of the exhibition allows you to give a certain autonomy to artworks, yet also juxtaposes artists next to each other and creates dialogues between them.

At EVA, the exhibitions that are installed in each venue have their own autonomous constellation of meaning. There are very kaleidoscopic, diverse, entry points to the biennial, rather than one single monolithic thematic. Part of that distance from having one single major statement is linked to the fact that we decided not to name the exhibition. In 1990, when EVA was curated by Saskia Bos – a Dutch curator who was the founder of a curatorial programme at De Appel in Amsterdam, which was a course that I did in 2007 – the introductory text of her catalogue for EVA says that it was the first time that the exhibition had received a title, because the exhibition was not only a selection of artworks, but it told a story. Since then, the curated EVA exhibitions have told stories; they have created narratives. I decided not to name this edition of EVA, on the one hand because of the multiplicity of significance and information that we are accustomed to, with our relation to technology and how we receive information. On the other hand, the idea of not naming it was to emphasise the already existing title of the organisation, which is EVA International, or more precisely, the word ‘International’ was something that I wanted to emphasise. Everything that has to do with signage for EVA – such as the image on the catalogue – the word ‘International’ becomes very prominent. The reason for this is in order to analyse how, in today’s world with the rise of nationalism, being international carries some kind of weight. I was thinking about transnational dialogue and transcultural community, which is something that EVA, from the cultural field, was at the forefront of. If you think about EVA in 1977 – an event in Limerick wanting to be international from the very beginning – that is what we are celebrating today, when that very liberal democracy is somehow under threat.

What other provocations were you either reacting against, or wanting to highlight when embarking on this curatorial project?

I do believe in the power of exhibition. For me it has been important to see how an exhibition can actually say things and change perspectives or worldviews of people, or can get audiences to be in touch with aesthetics that they have never encountered, or slow down the pace of audiences. Painting actually still has that power in today’s very heavy digital world. There’s a lot of painting. I think this is the first time in the exhibitions that I’ve curated so far, where a significant amount of painting is in the show. There’s a lot of figurative painting, perhaps that is resonating from the core of the exhibition that has to do with Seán Keating’s painting, Night’s Candles Are Burnt Out, which is a social realist painting and an allegory of the Irish psyche. There are other artworks in the show that are allegorical in their own ways, but there is a lot of allegorical painting.

Can you describe your first engagement with the Seán Keating painting, and how you’ve come to understand it since then?

This is my 6th trip to Ireland, which included a road trip from Belfast to Derry, and then from Derry down to Limerick, which is why there are a lot of Northern Irish artists in the exhibition. My first trip however, was to Limerick about a year and a half ago, and it was to understand the context, the art school, the venues, the art institutions, the people. On one of the first days, I visited the Hunt Museum, which is a landmark museum in Limerick, and behind the door there was this amazing painting. It was fascinating for me, because immediately I felt that it was a social realism that was very similar to Mexican muralism. As I started to research the whole body of work by Seán Keating, I thought, this is like the work of Diego Rivera! So I think that was my initial attraction towards it. Since then, there has been more time to understand certain characters that appear in his paintings, especially for example, the priest that appears on the bottom right of the painting. He is reading a bible by candlelight, looking towards the ground at a completely different angle than the Irish family who are pointing towards the horizon at the back of the Ardnacrusha power plant. Keating himself describes that part of the painting as: “The priest, reading the bible, represents the unchanging Church ever present when spiritual guidance is needed but concerning itself only with a kingdom that is not of this world”. I think that resonates with the present. In the eyes of Keating, the horizon that they’re looking towards is something that the whole Church was missing out on.

What other materials, for example in the accompanying catalogue, might provide further insight into the ideas behind EVA International?

There are incredible photographs of the construction of Ardnacrusha in the catalogue. Beyond being a civil engineering construction, the architectural style of it is Art Deco. Aside from being this machine, it’s quite related to the aesthetics of modern architecture. There is also documentation of other dams around the world that were instrumental for the construction of a nation-state. For example, there are images of the evacuation of Egyptian ruins, taken out from valleys that were flooded when the route of the Nile River was modified. This was done to make way for the Aswan Dam, which was instrumental for the Pan-Arab, Egyptian nationalism at the time. There’s also documentation of the most recent and largest hydroelectric dam, which is the Three Gorges Dam in China, built in the 2000s. The construction of that dam also flooded a very important valley in the middle territory of China, and displaced 1.3 million people living in different villages along the banks of the Yangtze River. The catalogue shows a narrative around how dams have been fundamental for that revolutionising moment of the economy of the state, or the idea of the electrification of the nation, as they called it back in the 20s, and the effect that Ardnacrusha had on industry by bringing electricity to places that had never had electricity before.

What types of spaces will EVA be taking place in?

Aside from all the discursive narratives that you try to deploy, at the end, the final gesture has to do with orchestrating an experience. That is definitely given by the venue itself. A lot of the works at Cleeve’s Condensed Milk Factory will be presented in a very singular format. In other words, there will mainly be the work of one artist per room, occupying a space. For the experience of the viewer, the collage is more mental rather than a physical, visual juxtaposition. In the case of the better-known venue, which is the Limerick City Gallery where EVA was founded, there’s more bi-dimensional work because of the Victorian nature of the architecture.

I believe there’s also work showing in Dublin.

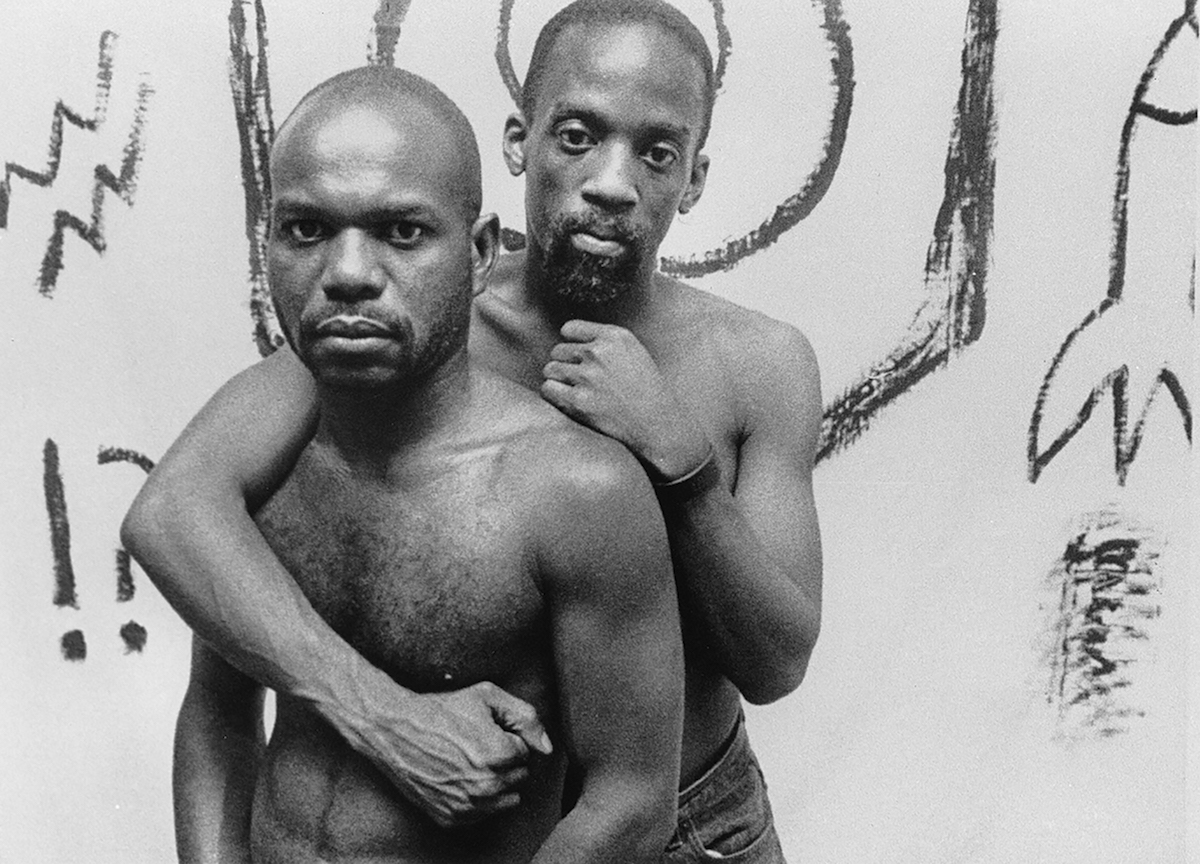

Yes, we also decided to have a small warm-up exhibition in the project spaces of IMMA. The work that is associated there is more on the narratives of nationhood, which is also at the core of that painting by Seán Keating. It is related to citizens, breaking borders, notions of and limitations of nationhood. Narratives that overlap are related to sensuality and the body. Comm is perhaps the most sexy of all the displays from the EVA exhibition, where sculptures simulating real human tongues are touching each other in an installation by Locky Morris. There is also a very intimate dialogue between two men on a fictional road trip from Lebanon to Palestine in a video work by Roy Dibb, which is a car drive Lebanese people can’t actually make because it is forbidden for them to cross into Israeli territory. It’s a video that crosses borders through a montage made with footage sourced by the artist’s friends across different parts of that landscape. There is an amazing short fragment of a landmark experimental documentary by Marlon T. Riggs – a main figure of the gay, black community in the late 80s and early 90s, which is the AIDS crisis in the US and across the world. There are also narratives that work together on how their own agency of citizenship, at that time, was created by establishing their own forms of language and communication.

Can you tell me about the inaugural event happening in Limerick during the opening weekend?

The inaugural event will be made by the Artist Campaign to Repeal the eighth, who are an agglomeration of artists, intellectuals, people in the field in the more civil rights spectrum, that have self-organised to have direct impact towards repealing the eighth amendment. They have already done banners, imagery, posters, and all types of props. These props are very performative, because they will be used in a procession through Limerick City. They are using different visual references to try to bring awareness towards repealing the 8th amendment. If you compare it to the very alarmist, sensationalist signage by the No campaign, the imagery of the Yes campaign is more grass-rooted, with banners that are hand woven and that have a certain individual and subjective texture that will be used by the many participants taking part.