Rodney Graham, That’s Not Me

Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, 24 November 2017 – 18 February 2018

That’s Not Me is a retrospective of the artist Rodney Graham, beginning with his work in 1994 to the present. This is the third significant exhibition held by IMMA of an artist from what is referred to as the Vancouver School of Photography, a loose term used by critics to describe a trend that kicked off in Canada/North America in the 1980’s, embracing both conceptualism and the post conceptual trend within photography. IMMA has exhibited some of its best known practitioners; Jeff Wall in 1993, Stan Douglas in 2015 and now Rodney Graham in 2017.

Consciously staged, meticulously detailed and concerned with the cinematic, this is photography – and occasionally, filmic work – which is reflexive of the processes behind its making as a wider allegory for truth, reality and the role of the artist. References to the past offer a subtle political critique, an impressive cultural literacy and a wry humour. But what have we learned about, and from, Graham’s contributions to this particular moment in photography?

That’s Not Me offers a partial account of Graham’s broad ranging oeuvre, with the notable exception of his breakout 1997 work in the Venice Biennale, Vexation Island. This exhibition takes a particular focus on his lightbox photographs and film work. In his review of the show, the Irish Times critic Aidan Dunne asked if Graham’s work is more superficial than Douglas’, the most recent artist from the Vancouver School to exhibit at IMMA, due to the mismatch between the “imposing physical scale of many of the lightboxes” and the “often slight import” that they address.[1] This isn’t an unfair critique. The intellectual weight of Graham’s work comes from a host of academic literary and cultural quotations that are certainly lacking the urgency of the engaged socio-political critique of Douglas. But it is in this shift away from the weight of a didacticism that something interesting about Graham comes into focus. The characters he adopts are caught in a sigh, a moment of defeat, exhaustion and depression, as shown in The Gifted Amateur, Nov. 10th, 1962 (2007), Actor/ Director 1954 (2013) and Smoke Break 2 (Drywaller) (2012). As much as photography itself is a subject of Graham’s work, the weight of the myth of the artist is given a cautious and celebratory attention.

“I don’t even own a camera,” the artist explained in an interview. “I work with photographers.” For an artist who has made such an impact in lens-based work, this is a provocative point to begin with for making art. A key distinction of Graham’s work at large, from those other artists associated with the Vancouver School, is the performative element throughout everything he does. Graham can be found within the frame of most of his photographs and films, which means someone else must be behind the camera and directing the scene as he explained in 2015: “I wanted to present myself as an actor/producer… I like putting myself in a situation where I don’t have complete control over the image. And if I’m the subject, obviously I have to be directed by someone else”.[2] During this post-photography moment, when artists were increasingly exploring every topic, theme and trope of photography, in Graham’s controlled and meticulously detailed work there is an undercurrent of both collaboration and chance guiding it all.

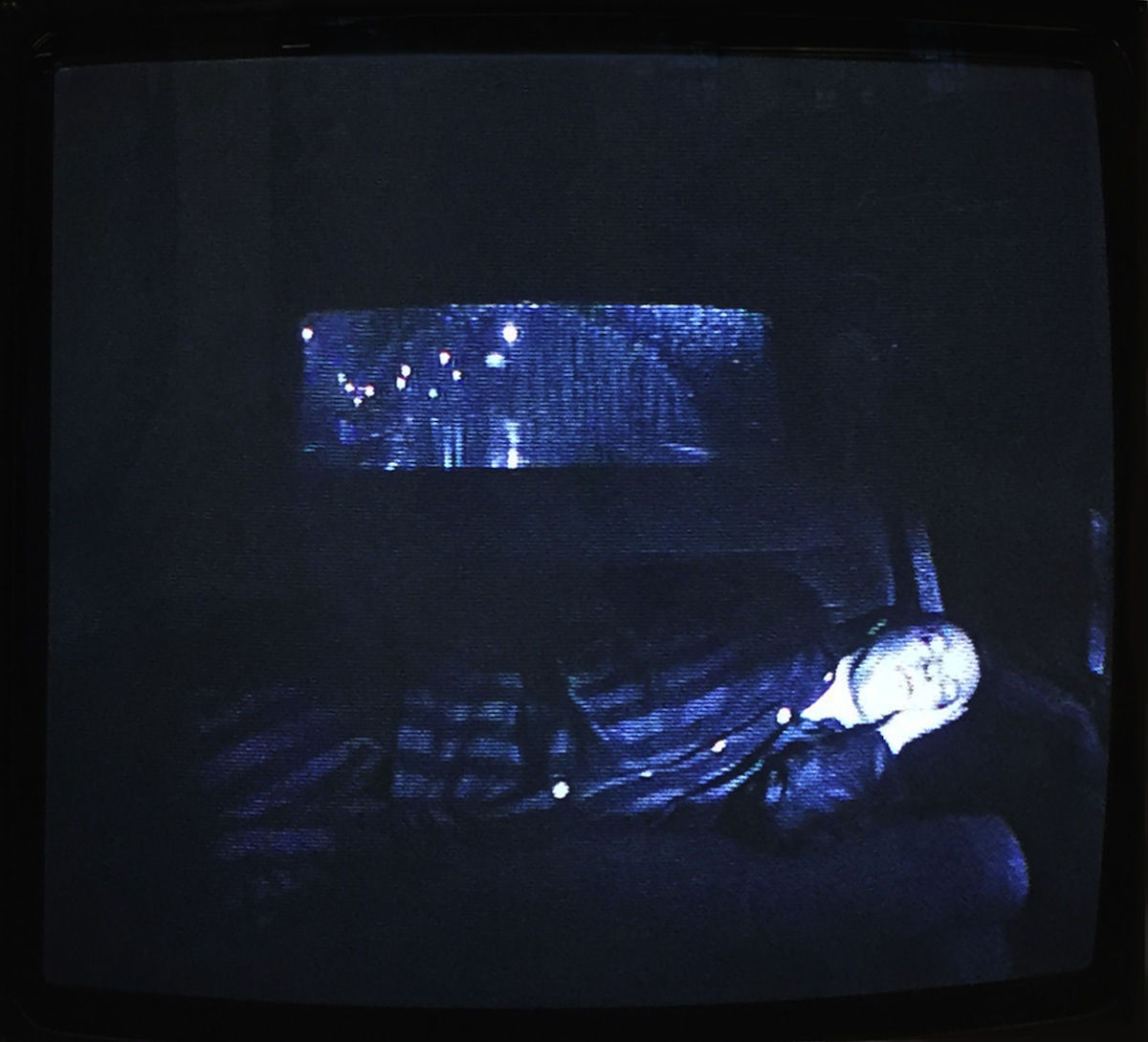

Halcion Sleep (1994) can be seen as a radical starting point in engaging with the notion of control and authorship directly. It is a single shot film of the artist in the back of a car, slumped over in a deep sleep despite the car’s movement. Here, Graham actually swallowed sleeping pills, rendering himself unconscious. He gave a set of instructions for what he wanted in the video and let the process take over. It has obvious implications for his photographic practice, and an unfolding conversation about the authorial nature of art making.

If the physical loss of control is one major feature of Graham’s practice, his meticulously detailed characters are another. The Gifted Amateur, Nov. 10th, 1962 (2007) is a triptych showing a man in pyjamas smoking and casually pouring yellow paint onto a light brown linen canvas, all taking place in a reconstituted 1960s period sitting room of an upper middle class family. The floor is covered in newspaper, and books about artists such as Picasso can be seen on bookshelves and stacked on the floor. It’s a laid back domestic scene. The everydayness of the creative process here is evident, as is the attention to period details. Artists seemed to have had a particular romance with painting around this time, with Abstract Expressionism firmly established and blossoming and other approaches to abstraction taking place across North America and abroad. Yet, in Graham’s image the artist is shown as more of a hobbyist with none of the intensity of a Jackson Pollock or the moroseness of a Mark Rothko. There is something about the excessive macho posturing of this particular ideal of the mid-century American painter that Graham is both fascinated by and poking fun at. This playacting doesn’t end with laughter though, as Graham has fully embraced these characters he’s adopted for photography and film, even exhibiting art works made in the style of these characters – a further commitment to and a deeper confusion of authorship.

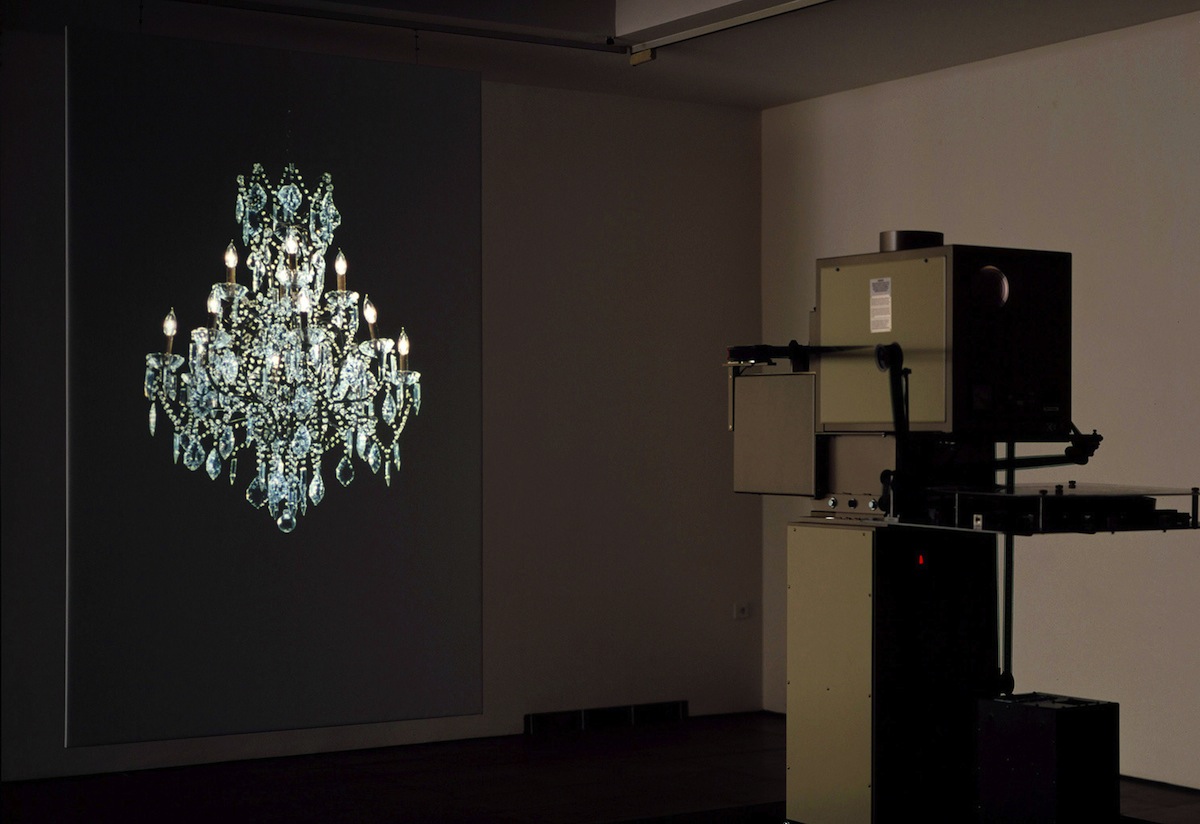

Graham is clearly fascinated by the role-playing of characters, time periods and the idea of the artist himself. The theme of obsolescence is here too, with obvious implications for the roles we play as shaped by society and technology. The video projections featuring in That’s Not Me draw attention to a more experimental aspect of Graham’s production. Torqued Chandelier Release (2005) is one such work that is both performative and concerned with the specific time and materiality of its tools. Here we see a chandelier rotating, and all the action happens within a single roll of film. Graham describes this series of works as “illustrated ‘thought experiments’… within the context of a single roll of film.” The film was shown through a remarkably large projector – as were the other films in the series – and due to the oversized nature of the apparatus both the sculptural quality of this work and its time specificity are heightened. These means of production are deliberately outmoded, as are many of the cultural points of reference.

There is a significant amount of mainstream cultural attention given to a certain kind of retro masculinity, often explored through a dramatic empathy with the patriarch. In classic cinema and the more contemporary prestige TV, this is shown through the sad eyes of Mad Men’s Don Draper, the heavy shoulders of Tony Soprano, or the regrets of The Godfather’s Michael Corleone. These stories of sexism and power are retold with a wry, ironic smirk. This period in history resonates with audiences, in part, because the relationship between men, power and domination is still so clearly relevant, yet due to the time gone by it feels safer, more distant, and can be dramatized, despite the very real and continuing consequences behind these narratives.

In recent years there have been a number of retrospectives of high profile photographers who emerged in the 1980s, motivated by the key debates of the time and their legacies. Just this year in London, the Thomas Ruff exhibition ended at Whitechapel and Andreas Gursky re-opened the Hayward Gallery. Partly this is explained by the fact that many of these artists are simply at that point in their career. Mostly male and over 60, it is a generation of artists who grew up alongside the rise of advertising and the birth of digital technologies. While their work doesn’t as directly address this as, say, the Pictures Generation or Net Art did, this is often a tangential curatorial framing alongside more art historical themes of the image and authorship, painting and photography, and so on. The level of institutional attention invested in these artists is significant, as is the curatorial approach that grants such generosity. These artists are permitted to be both socially relevant and connected to wider art historical themes in a way that women and artists of colour aren’t, often ghettoised by terms such as a Feminist or Black art history in a way that white, straight men never are. When I visited, the fact that IMMA was holding concurrent exhibitions from older white men, Rodney Graham, Ciaran Lennon and Brian Maguire, highlighted and intensified this reality.

Graham has made significant contributions to photography, and is a notable figure now within and beyond the Vancouver School of Photography, mostly due to his performative and often inventive approach. He is working in and around masculinity, role-playing and the passage of time. It would be simplistic to dismiss his work as old-fashioned, although it is certainly invested in the outmoded and outdated. Due to the wider perseverance of the patriarchal figure on our screens and across society, there is clearly something important about recognising and questioning the continuing attraction and sustained cultural pull of this recent cultural past, while considering what might be the alternatives beyond this.