Roee Rosen, Exorcisms at Project Arts Centre

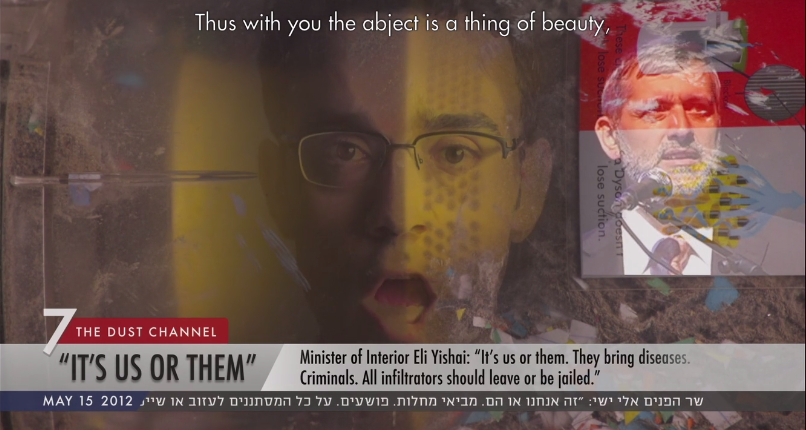

Roee Rosen is a political provocator. Watching the work included in Exorcisms at Project Arts Centre is an experience akin to a guilty pleasure: we laugh, but we know we shouldn’t. It is hard not to laugh at the story of a couple in a love triangle with their Dyson vacuum cleaner. It is when the cleaner itself starts exploring the Dyson heritage and the cultural context of the lives of foreigners and asylum seekers in Israel that the guilt appears. We feel guilt because we know how asylum seekers are treated (and not just in Israel), but the operatic, repetitive “sosat, sosat, sosat” (suck, suck, suck) from earlier in The Dust Channel (2016) is still playing over the grim descriptions of reality. In an interview in 2017[1], Rosen himself described his art as a pleasure trap that puts the audience in a position where they have to think about reality. We are caught.

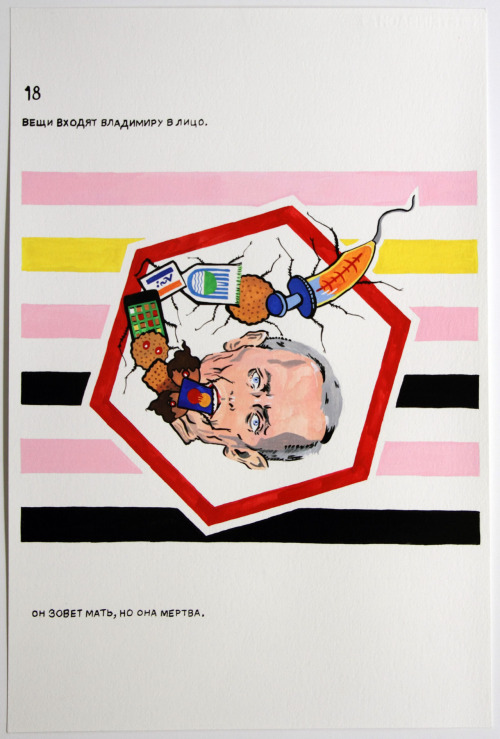

“Being Israeli,” said the artist in 2018, “is an active aspect of your identity, whether you like it or not”.[2] But not all of us know how to own this identity and critique it as poignantly as Rosen does, giving the political story its due weight. Rosen critiques Israelis’ ability to live their mainstreamed lives alongside the crumbling fringe in Israel and Palestine, but the politics as well as the critique is relevant beyond our disposition as Israelis. Putin-like politics is a problem many contemporary political cultures have been facing recently. In Exorcisms the work ridicules Putin with grotesque and suggestive illustrations of the Russian ruler in compromising positions. These illustrations, as well as The Buried Alive Videos (2013) moving image installations, are produced by a completely fictional collective of Israeli ex-Soviet poets and artists, invented by Rosen. Once again the pieces create discomfort. Mimicking the aesthetics of terror-related abduction videos Rosen, as the collective, produced videos showing Israeli cultural figures as prisoners of the artists, told by their captors to tell jokes on camera.

Out (Tse) (2010) in turn, takes as its target Avigdor Lieberman, a Soviet-born Israeli politician whose words and voice come out of a BDSM submissive’s throat when her dominatrix performs an exorcism. Divisive words of hatred of the other, racism, and radical nationalism and corruption. These words are familiar in many contemporary societies, spoken by political leaders and adopted by popular discourses. The work provokes guilt for allowing ourselves to continue living in such societies, the guilt in the recognition that Rosen’s work presents facets of our reality.

In her article on guilt-based filmmaking, Mette Hjort states that “Historically, guilt has been theorized as […] constructive and reparative on the one hand, and destructive and paralysing on the other.”[3] But these options are not mutually exclusive. Rosen’s work disarms the viewer with humour and uses representations of reality as a means to peel away our defences. The humorous content raises curiosity to encourage research and reparative actions as a potential outcome after the paralysing shock of facing difficult content. The guilt comes from the recognition of the work as a chronicle of a despair foretold. We know that outside the gallery the victims of the politics staring at us from the work in Exorcisms are already gone.

Moran Been-noon is an Israeli independent curator and artist based in Dublin.