Liam Gillick, A Depicted Horse is not a Critique of a Horse, Kerlin Gallery.

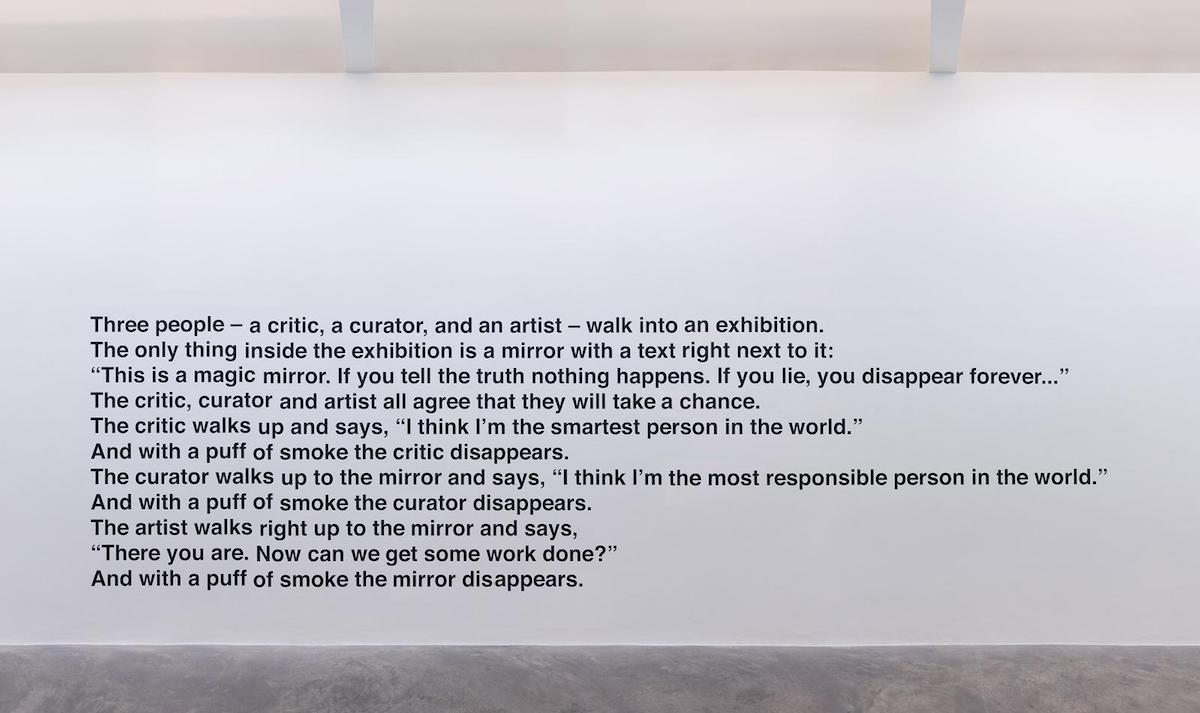

Where a dream is but passive fantasy, a work of art constitutes the act, and A Depicted Horse is not a Critique of a Horse, Liam Gillick’s most recent exhibition at Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, takes the form of a multilinear map concerned with it all: dream and fantasy on one level, production and consumption on another. Comprised of seven large-scale reproductions of medieval woodcuts, six abstract ‘channel works’ and one wall text entitled: What is a mirror for? (2018) which combines elements of humour, fairytale and art-critical animadversions, we find the usual semiological play we have come to expect from Gillick, but what of the symbolic? For a sign always points to a known entity and a symbol to the unknown.

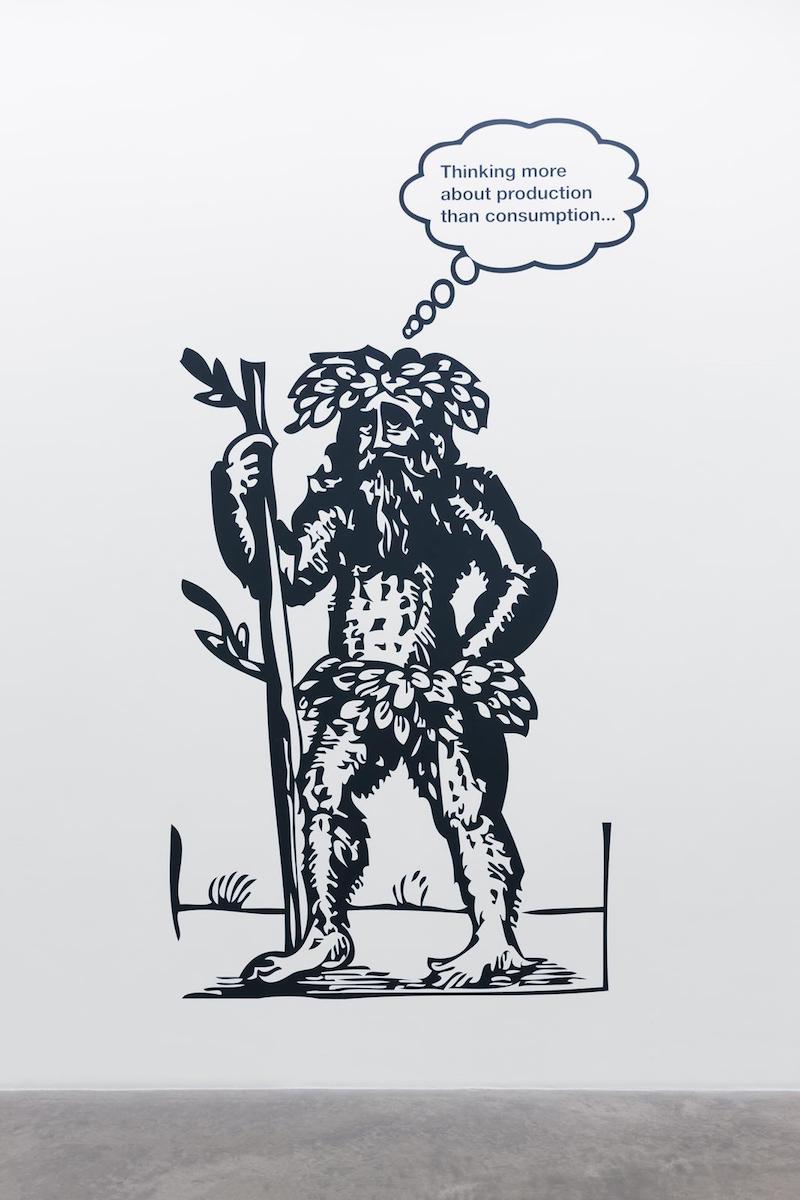

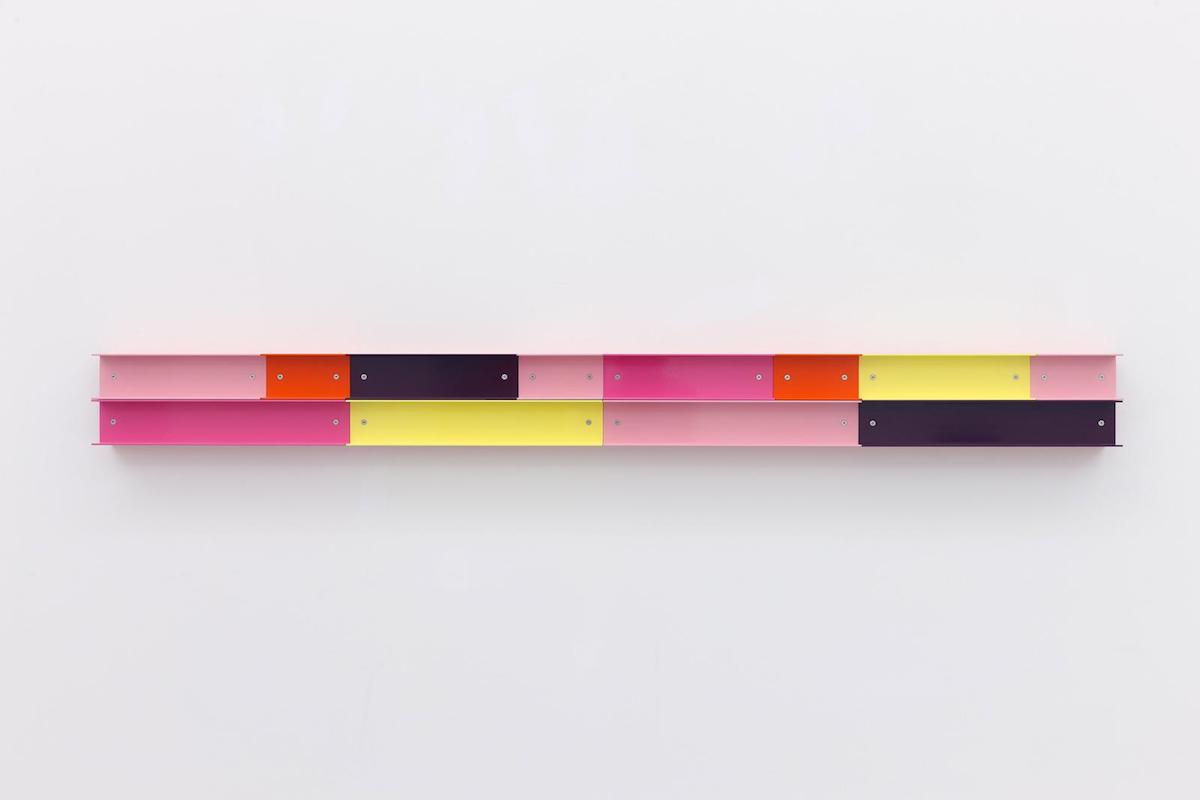

Matte black vinyl transfers medieval image to gallery wall juxtaposed with contemporary adage. And linking each large-scale graphic, runs horizontal a series of ‘channel works’ individually titled as Consumption, Restriction, Expansion, Liability, Refusal, Contagion – Channelled (2018). These powder-coated aluminium structures are segmented by colour, vary in height and width but measure always a depth of 8cm. This repetitive interchange between what is represented by way of black vinyl and these three-dimensional colour-coded abstractions call for an oscillated reading, one which seeks to abandon the normal conventions of chronology.

The medieval illustrations recall to mind the time of their first expression. This was a time when alchemy was flourishing and alchemical imagery permeated medieval visual culture. C. G. Jung wrote extensively on the relationship between psychology and alchemy. He saw this early form of chemical experimentation as more than a failure to materialise on the ‘Great Work’ i.e. the transmutation of matter – turning base metal into gold by way of the elusive lapis philosophorum. Instead, Jung found alchemy to be an expression of psychological development whereby the alchemists were projecting aspects of the unconscious psyche into their work and accompanying imagery.

At first glance, stencilled reproductions might feel a little flat save for the thought-bubbles which encourage something of a mental engagement. However, upon further reflection, Means of consumption… (2018), for example, presents man as archaic fact, perhaps a symbol for that subhuman aspect of the psyche; in this instance “thinking more about production than consumption”. And while that all too familiar figure of St. Sebastian pierced from head to toe with arrows, knives and swords thinks about the accounting ratio: “Return on capital employed…” (2018), we are also reminded of the first stage of the alchemical process known as ‘nigredo’. This somewhat mysterious figure is also a “common alchemical image symbolising the violence of putrification following the marriage of opposites. Pain and suffering were most important in the stage of the process known as ‘hell’, as the final distillation was only reserved for him who is wounded and given over to death.” [1]

Each image can easily be read by way of semiotics due to their graphic nature, but at the same time a symbolic reading can only but amplify the meaning to a greater effect. And while the ‘channel-works’ are said to be “derived from elements that support or disguise architectural structures”, by situating these three-dimensional abstract sculptures between each representational image, Gillick creates one single channel from which to look forward and back for “everything of psychic origin has a double face.”[2] Divided into coloured subsections, these metal light-codes serve as a medium for the unconscious by drawing upon the rudimentary structures that underpin time as a fourth dimensional correlate to the mind that has been activated by the seven illustrations.

Alchemy was concerned with the mystery of transformation. The alchemists were in fact transforming themselves as they peered into the unknown, contacting their unconscious. And similar to the alchemist, the artist also, is concerned with transmutation. According to Jung, “an artist is not just a reproducer of appearances but a creator and educator, for his works have the value of symbols that adumbrate lines of future development.”[3] Gillick’s use of medieval imagery and elemental structures trace out a line of developmental pursuit on a collective level, a trajectory spanning centuries, from medieval woodcut to the very contemporary vinyl print, from early forms of labour, transport and production to modern typography, thought-bubbles and titles that connect past with present along a production line of future development which apparently all ends in consumption.

Liam Gillick, A Depicted Horse is not a Critique of a Horse, Kerlin Gallery, Dublin, 23 November 2018 – 19 January 2019.