Lynda Phelan: Zara Sargent

Zara Sargent’s Time and Time Again

Located on the first floor. On a balcony. Sargent takes the wall to the left. Time and Time Again – aptly poised. A step too far and you might just fall off the edge. Below, a repurposed church-cum-gallery. Nestled under its weight from above: Time and Time Again – presenting something of our power over paradigm.

Our eyes meet first the vibrancy of colour. The choice of which is indeed of the now, countering well the anachronistic imagery. Time and Time Again – reproducing old masters in a colour range more akin to Pantone’s Colour of the Year (2000 – 2019). The selection of imagery is telling. Centuries-old portrayals. A recurrent theme then as now. Power-OVER otHER.

Time and Time Again – the same story. Punctuated three times. We read “…someone had taken advantage of me in my supposed ‘safe place’…” Breaking the Silence – in Cyan, Lilac & Magenta. Now. 2019.

Then. 1806. Tischbein painted a picture inspired by the ancient Greek story of Cassandra. No one listened when she foretold the fall of Troy. As the city crumbled, Cassandra sought safety in the temple of Athena. Tischbein painted. Cassandra – abducted (– raped) by Ajax the Lesser.

Now. 2019. Sargent reappropriates this work by way of silkscreen. Moving from left to right, orange into red, Cassandra falls into Ajax and we dread the worst. Everything exposed. The lysis points to a brutal act. Sargent says in embossed lettering: Let Cassandra’s Voice be Heard.

Then. 1621. Gentileschi painted a picture inspired by Lucretia. Advances refused. Raped by the King’s son. Lucretia was to take down the monarchy. Before witnesses she confessed all. Before plunging a dagger into her heart she called for vengeance. Spilled blood stirred revolution and a republic was born.

Now. 2019. Sargent reappropriates this work by way of silkscreen. Lucretia takes the frame. Self-possessed in blue. The hand that grips the dagger, the hand that grips her breast. Action shot – a lighter shade. Sargent says in embossed lettering: Rapists are the Only Cause of Rape.

Then. 1634. Poussin painted a big mythological scene. Romulus, first king of Rome, sanctioned the large-scale abduction [raptio] of the Sabine Women in order to strengthen his rule. From raptio [Latin] – the word rape [English]. Now. Sargent holds her tongue.

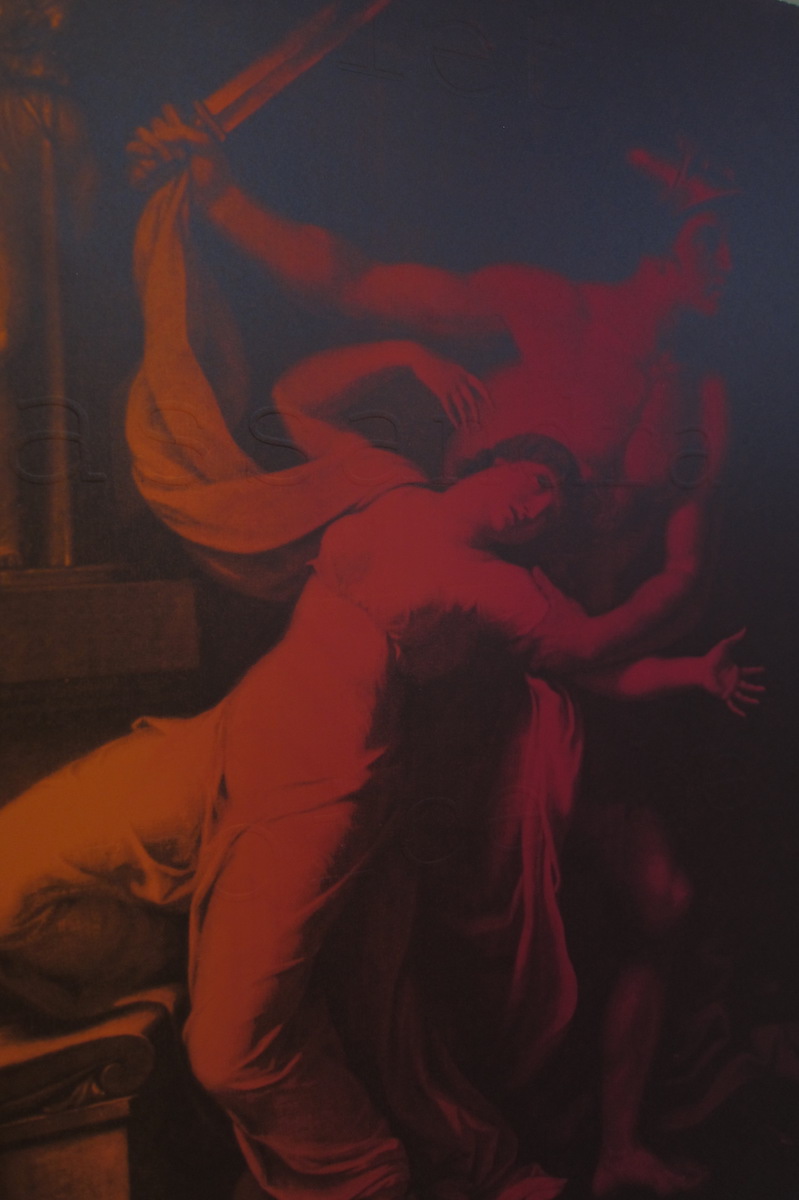

Then. 1610. Gentileschi painted Susanna. Bathing alone. The Elders intrude and gaze upon her naked flesh. Her private space violated. An art historical trope: male artist, voyeurism, and an ‘unsuspecting’ female nude. Sargent says in embossed lettering: Boys will be Boys if you Let Them.

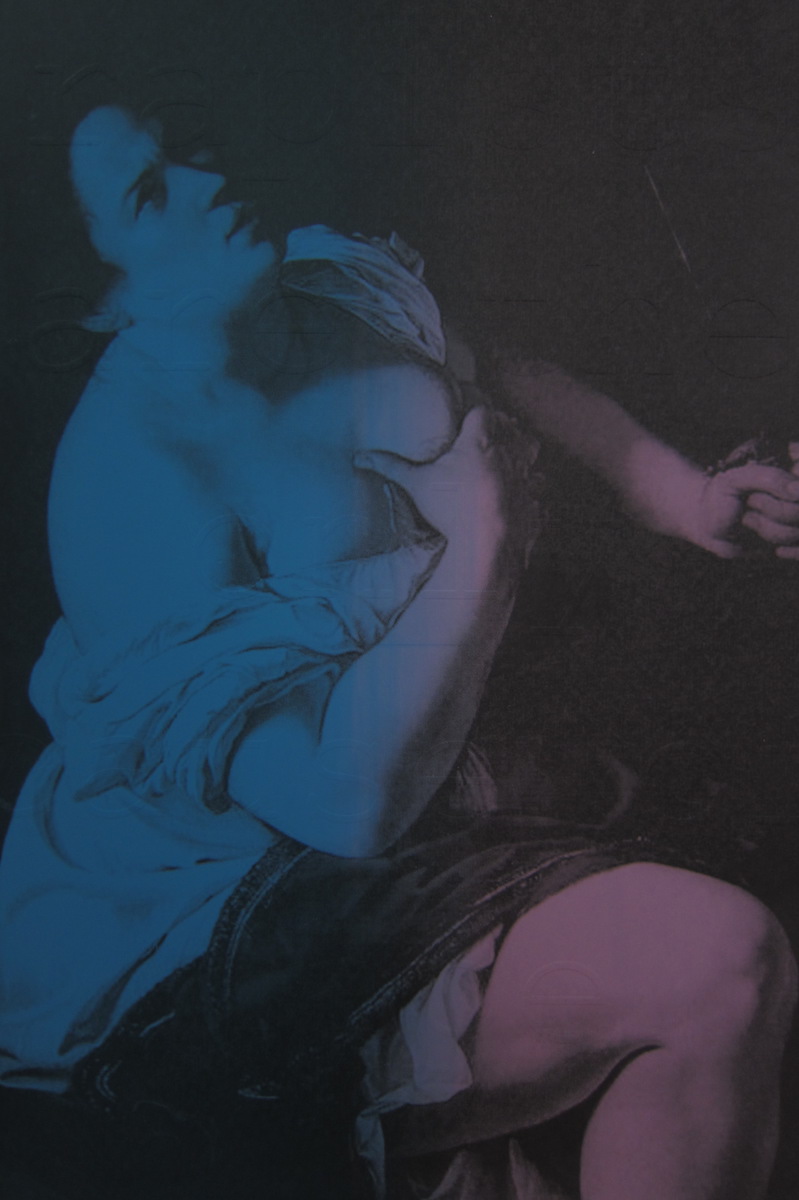

Then. 1622. Bernini carved out of marble the abduction (– rape) of Proserpina [Roman] – Persephone [Greek] by the god Pluto [Roman] – Hades [Greek]. A well known tale of the goddess’ descent into the underworld and how she became forever tied to her darkness through the eating of his pomegranate seed(s). Sargent says in embossed lettering: Shame belongs to Rapists not Victims.

Jung saw in mythology evidence for a psychic sub-structure shared by all: the collective unconscious – the contents of which are made up essentially of archetypes. Archetypes are loosely defined as pre-existing collective patterns that exist prior to consciousness. When one compares stories the world over, archetypal patterns begin to appear in the form of recurring motifs mirroring our socio-instinctive behaviour. Jung understood there to be a distinct correlation between psychic structure and psychic phenomenon and that of reality – on some level making all cultural production demonstrative of our collective psychic reality.

Freud saw the human psyche as layered and bound to the past. He further observed an inherent compulsion to repeat, to reproduce repressed material as contemporary experience. With our psychical foundation being bound by repressed material, how does this bind find its expression reproduced as contemporary experience? Art might just provide the answer, for “art is a kind of innate drive that seizes a human being and makes [her] its instrument” (Jung 1933: 173).

Time and Time Again – recalls to mind how we produce work as an instrument of art. Creating, recreating, producing, reproducing reproductions – for there is nothing new under the sun. Sargent repeats, re-imagines and reproduces ‘new’ work using an already well-established art-historical mythopoetic visual language. The artist – open and susceptible to being given over to imperceptible guiding forces – is clearly a good candidate for the deployment of old material as contemporary experience. This artist has been used well.

![Zara Sargent, [Detail] After Gentileschi - \](https://circaartmagazine.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Zara-Sargent-LSAD-Detail-After-Gentileschi-Susanna-and-the-Elders-Boys-Will-Be-Boys...-If-You-Let-Them-Silkscreen-Blind-Embossment-2019.jpg)

![Zara Sargent, [Detail] After Bernini - \](https://circaartmagazine.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Zara-Sargent-LSAD-Detail-After-Bernini-The-Rape-of-Proserpina-Shame-Belongs-to-Rapists-Not-Victims-Silkscreen-Blind-Embossment-2019.jpg)