13 BC: Fatal Act at the Douglas Hyde Gallery

Created by Vic Brooks, Lucy Raven and Evan Calder Williams who together make up the moving image research collective 13BC, this exhibition at the Douglas Hyde Gallery leaves nothing to assumption. Everything is laid bare, connections are made and outlined in excruciating detail. All you have to do is offer up your time to watch, to listen and to read.

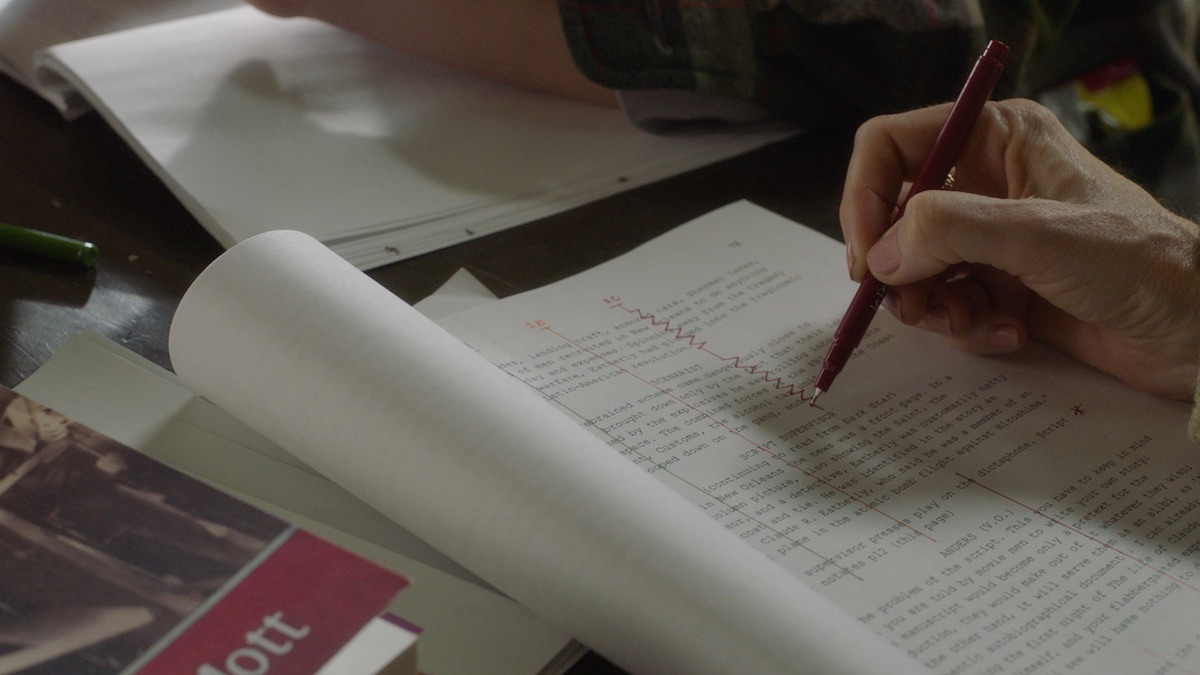

At least that’s what you’re led to believe. In Straight Flush, 13 BC reveal the post-war correspondence between Claude Eatherly, a US Air Force pilot who gave the ‘all clear’ weather report for the bombing of Hiroshima, and Günther Anders, a German philosopher who believed that war veterans experienced so much guilt following WW2 because they were unable to adequately understand their destructive impact with advances in nuclear technology. This correspondence is weaved around the subject of the unmade biopic of Eatherly’s life that was proposed by Bob Hope. Anders warned Eatherly that by complying with the release of such a film it would falsify the fatal act of bombing Hiroshima, depriving it from its ‘deadly seriousness’. All of this is revealed as the film’s three protagonists read from a script with regular interjections from an invisible speaker on a radio placed at the centre of a table.

Through Straight Flush we are witnesses to 13BC’s ability to unveil historic connections and coincidences. When watching the film, my concentration is broken by information overload. I wander and begin to fixate on the centre of the table and the poker chips. The film’s title is derived from the name of the aeroplane Eatherly flew over Hiroshima, and while this provides a literal connection between the film and the aeroplane the poker chips detract from the deadly seriousness of the subject. They become symbolic of Straight Flush’s relationship to the biopic that Anders warned against and the trust I initially bestowed on 13 BC begins to break down. It is as though the producers are laughing at us, presenting tokens from a game that rewards bluffers and liars, and the actors’ regular smirks seem to attest to this.

The fact that the film takes place in a decommissioned barracks and current military testing ground adds to the confusion of Straight Flush. There is a complicit link between the performative nature of the film industry and the US military who rehearse their destructive actions. Some consideration must also be given to the location of Corpse Cleaner – a costume and prop house. Everything, from the outfits worn by the actors to the cigarettes they smoke, has been carefully manufactured and considered in Straight Flush, and like in all movies they are executed with military precision.

13 BC are also interested in the images that have become synonymous with war. Act 1 shows eerily beautiful images of a sun setting on a pink sky over the decommissioned barracks that Straight Flush was filmed in. The piece refers to the way in which chemical film and digital cameras translate light into colour and the post-processing that is required to make the image readable to the human eye. This implies that there is always an oscillation between the accuracy of historic events and the images we use to understand them.

Fatal Act is an exhibition full of content ready to be dissected, analysed and over-analysed, but the feeling that emerges from this exhibition is one primarily of anxiousness, distrust and uncertainty. If Anders was right in his supposition that the post-war years were dominated by guilt resulting from the inability of humans to understand their impact in the nuclear age, Fatal Act highlights the prevailing anxiety around misinformation in the digital age of the 21st century.