‘Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered’

Jesse Jones, Tremble Tremble

Project Arts Centre, 8 June – 18 July, 2018

Above all magic seemed a form of refusal of work, of insubordination and an instrument of grass roots resistance to power, the world has to be disenchanted in order to be dominated’

Silvia Federici. [1]

I

Timing is everything. When Jesse Jones presented her multi-media installation Tremble Tremble in Venice last year as Ireland’s national representation at the 57th Venice Biennale it registered an impact beyond what might be expected from a small country with no designated national pavilion and a relatively short history of participation in the international art biennale.[2] It wasn’t just the two 20 foot high screens dominating the Irish enclosure at the far end of the Arsenale, nor was it the immersive soundscape that seemed to quieten and hold the attention of the passing throng, or the writhing female figure, twinned on double screens, that pounded, danced, cursed and mocked. With specific intention the artwork was presented as part of a politics of protest emanating with a swelling voice from Ireland and becoming quickly identified as a work that carried a very specific feminist message. The conceit at its core drew attention to the momentum building at home as activists, artists and women everywhere organised collectively for the Campaign to Repeal the Eighth Amendment, Irelands’ repressive abortion legislation.

Jones acknowledges that when the work was first shown in Venice she was “conscious that she was representing the politics that was then unfolding”.[3] The Law of In Utera Gigantae, the proposition central to Tremble Tremble, is both radical and somehow rational:

Whereas from the moment a human being begins to take its place of dwelling in the maternal belly, it lives inside a giant. The state acknowledges and affirms that the life of the giant, in virtue of her status as the origin of all life, shall be protected and vindicated before all other emerging lives she may generate.

Challenging the Irish judiciary and “changing the imaginary around the law in this threshold of change” was something that Jones had been considering for some time. In her early research for Tremble Tremble she thought about constructing a large architectural model of a courthouse and exhibiting it upside down.

The idea took many shifts and turns as it evolved collaboratively to become the installation seen by huge numbers during its exhibition in Venice last year, later in Singapore and now in a more developed iteration in Project’s Space Upstairs. Though the idea for the courthouse was later dispensed with, some props appearing in the film such as the lectern or church furniture of a particular vintage, do convey a sense of the trappings of church and state. Jones consulted with Mairead Enright, lawyer and leading activist in the Repeal campaign to get the precise wording for the new law, adamant that it should strike the right authoritative tone.

She acknowledges Silvia Federici as a touch stone for her practice; the title of Tremble Tremble is not, as might suppose, about the fear one might feel from being dwarfed and hounded by an angry giantess but, from the phrase “Tremate, tremate, le streghe sono tornate!” (Tremble, tremble, the witches have returned) the rallying call of Italian women in the 1970s when the Wages for Housework movement was formed. Led by Federici it made a strong case for a living wage to be paid to those engaged in domestic labour and for abortion rights. Federici has written extensively from a Marxist/feminist perspective and it is her writing Caliban and the Witch that is a seminal influence and source for many of the ideas that find form in this work. Which begs the question, even at the outset, as to how necessary is it to know the source material in order to grasp the point of Tremble Tremble? While it helps to be aware of the influences and references (of which there are many) they are not crucial to seeing and enjoying the work, at least superficially, because its initial appeal is both visual and visceral.

It’s worth knowing though that Jones has pursued a collaborative practice for some years. She identified her partners for this project early on, certain that she wanted to work with Olwen Fouéré, an actor and performer who has collaborated with many visual artists. Fouéré introduced her to Susan Stenger whose way of working “in an almost forensic way” with sound and geology very much appealed to Jones and Tessa Giblin, former curator at Project and commissioner for the Venice representation was central to the collaboration. Given Project’s role as production partner and its prominence in the Repeal The Eighth Campaign as an institution backing the call for change, the installation was always destined to come home to this venue. For all involved Project was “always the ideal situation for the work”.

II

It’s fourteen months since Tremble Tremble opened in Venice and less than two since the Irish referendum to repeal the eighth was won by a significant majority. The exhibition in Project is already in its sixth week and every day the multimedia artwork, encompassing film, sculpture, sound and performance is activated and recounted about thirteen times as the two films loop, and one encompassing narrative unfolds. Sounds reverberate, words are uttered, echo and repeat. At the end of the narrow entry to the darkened space a single sculpture of a giant polished bone is spot lit and presented as an upright form, it hovers almost, in and out of our field of vision. Two enormous screens at either end of the space vie for our attention but, it’s to the centre of the space that one gravitates; here, performers pull over and back, long floor to ceiling transparent curtains that hang from two curved rails and which carry on their surface the image of two outstretched arms. Rhythmically and repeatedly the curtains open and close, arms pull the arms, and the curtains’ role is to reveal and conceal, demarcating not just a space within the space, but a new focal point in the installation.

A granite millstone has been placed in the centre of the curtained space. It’s a simple form with multiple associations, and exerts a strong presence. While the curtains function both to direct the movement of the visitors becoming part of how the space is choreographed, it is at the edge of the circular stone that one sits or stands to first absorb the experience. The millstone becomes a gathering place for visitors and for the female attendants who play a quiet, but critical, role in how the work unfolds. Occasionally the artist takes on the role of attendant, engaging in the work and ensuring that the choreography is precise and consistent.

Time is physically marked out as halfway through every performance one of the attendants takes a chisel, with the word haxan carved into its handle, from the central well of the stone and incises a circle into the wall of the exhibition space. The ritual is loud and laborious; with two hands and a degree of bodily effort, the attendant drags the chisel around, the natural motion of the arms, drawing and enlarging the circle every day. Time passes, its cyclical nature visibly demonstrated by the dense, expanding whorl of marks that bears witness to this work and the work it took to make it.

The politics of work has been considered by Jones before. In 2016 No More Fun Games at the Municipal Art Gallery reflected on the nature of labour, gender politics and the pay gap. For one of the programmes that formed part of that project (specifically Act II of the feminist parasite institution) the themes of labour and gender equality were actively addressed; female performers were assigned the task of pulling heavy screen curtains and paid hourly for their work. Michael Dempsey the curator of the project wrote at that time:

To look at the swishing movement of the curtains is certainly a beautiful thing but the aesthetic gain achieved by this action stands in an ironic implication to the ethics and implications it raises i.e. the twofold nature of women’s exploitation. The curtain now acts as a signifier to the domestic .presented as a re-enactment of a domestic service and throwing up a host of confusing ideas about inequality and gender ideology.[4]

Here again in Project the curtains and the performers are major players in the exhibition. Beyond the questions they infer about the nature of work, pay and gender however (and it would be interesting to know exactly how much the performers are paid and their ‘terms and conditions’ for enacting their daily labour), one has to credit the effectiveness of the curtains as a theatrical and framing device. Jones has spoken several times of her strategy of creating an ‘expanded cinema’ and, yes, viewing the hyper-real imagery presented on the two screens through and between the swathes of black voile is quite a sensory experience. There is a moment, when the two curtains meet and the giant hands imprinted on their surface, very briefly, appear to caress and touch. Amidst all the loud sounds, the enlarged imagery and the sonorous narrative emanating from the screens, for me it was that quiet moment that stood out.

III

Even before one focuses on the two screens in the greater space competing for our attention, the soundscape conjures an atmosphere that is eerie and elemental; the hum and thrum of a low, constant, base note provides a backdrop for the more melodic top lines, pipes, flutes and an intermittent theremin suggest spooky windswept plains and vernal spheres where dryads or goblins might well wander. Susan Stenger’s composition is a great foil for the conflated Giant/ Witch/Crone character played with a ferocious intensity by Fouéré. Mostly, the giantess looms large, a massive, but not actually threatening, presence in the space. When she crouches and squats so her face is at a level with ours and as the sound ramps up, there is a slight ‘frisson’ but the figure provokes rather than disturbs. When via very effective camerawork and projection the crone rises up, she does indeed appear giant-like, towering and impressive in the space.

In the realm of European mythology female giants are notable for their absence. It’s not that giantesses were written out just that they seem never to have been there in the first place. The mythmakers, it seems, could be deemed guilty of unconscious bias and the archetype is decidedly male. In Irish mythology however (as Tina Kinsella observes in her essay for the exhibition catalogue), there are a few exceptions, specifically Badb Catha a giant war goddess who could “spread fear and confusion amongst soldiers on the battlefield”. She also mentions an interpretation of the Sheela-na-Gig fertility sculptures by a Scandinavian scholar Barbara Freitag, alluding to a nineteenth century study claiming that ‘gyg’ in Norse is the name for a female lotun or giantess. This early nineteenth century reference apparently interprets Sheela-na-Gig, as meaning ‘Image of the Giantess’. Nowhere in the literature relating to the project could I find reference to An Cailleach who was a powerful and significant figure in Irish mythology, more a crone than a giant but feared and fearful, flinging stones and rock as she moved through the landscape and wielding power over life and death.[5]

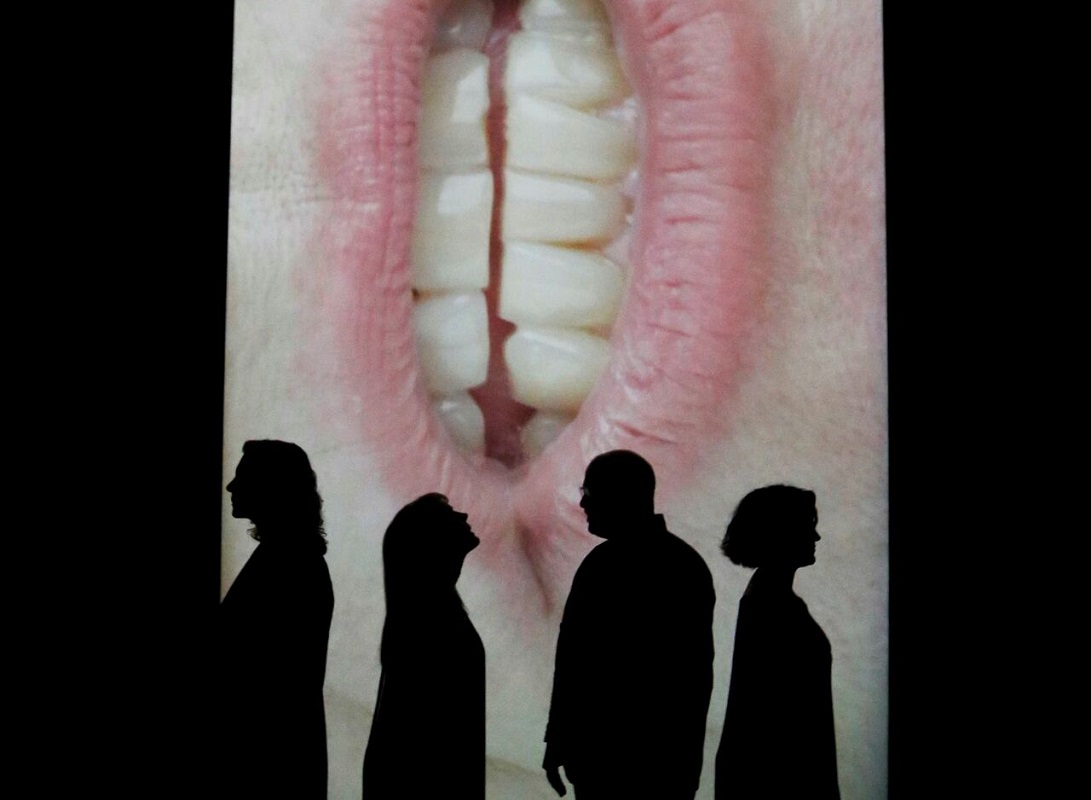

Fouéré brilliantly conveys a sense of the Cailleach as she drags her ropes, wields her threats and spits her venom. However, it’s the exposed vulva of the Sheelagh-na-Gig that comes to mind, alongside a whiff of Freudian mischief, when at a pivotal moment in the film an enormous inverted mouth fills the screen and through teeth that clench and unclench the solemn edict is proclaimed;

Before the body of the law was written in earthly tongues, there existed another law, passed down through generations from mother to daughter. Its letters were written in milk and spoken in whispers.

The new law to be upheld is enshrined in the body of the Giantess who “possesses the double kindness to create or destroy the life she carries.” It’s a weighty text and a complex subject but not without poetry:

This brief stay is the only true law a human will ever know, its borders made of bones, the sound of flowing blood its only universe, its architecture made of tears and laughter.

The Law of In Utera Gigante is at the heart of Tremble Tremble and while Fouéré boldly and intensely plays out roles within a role – giant/witch/hag/crone/dancer and disrupter, it’s the script, rhythmical, resonant and pared down to essentials, which holds the narrative together. Jones has tapped into a broad sweep of sources, from the Bideford Witch trials of the seventeenth century – Did I disturb ye good people, I hopes I disturb ye…Have you had enough yet? Or do you still have time for chaos?… You won’t forget us even if you try and sweeps us away, you who survive will mean nought and Temperance knows you’ll be sorry…– to the very awful Malleus Maleficarum (the guidebook to the persecution of witches first published in 1487), to excavations in Ethiopia in the 1970s, the latter unearthing the fossilised bones of Lucy the earliest skeleton of a human female dating from over 3.2 million years ago – I was walking by the side of the river almost three million years ago, my body sank into the earth, centuries passed and the river dried and swelled. Every cell in my body was eroded, particle by particle until I became a stone, hardened, I became a new She, more a thing than a woman, the other of the other…

In her introductory essay for the catalogue Tessa Giblin says Tremble Tremble revolves around “a search for a possible other, a plausible ancient truth” and Jones has spoken of her wish to intimate an idea of “the ancestry held in our bodies”, how she wanted to create a sense of “the ancestors being called into the room”. That intent is played out visually and sensually when the camera with its macro lens, pans over the animal skin worn by the hag and then slowly and lovingly over her body, skin on skin, flesh and follicles enlarge and abstract until they look like mere cells and surface matter.

Here at Project many new ingredients have been thrown into the mix and one must decide for themselves if the several additions weaken or strengthen the brew. The real challenge of Tremble Tremble is that to feel its full effect you must do your own foraging. Jones’ research has been far reaching and it takes a stretch of the intellect and the imagination to discern all the connectors that together link the components into one extensively nuanced text. Whether because of, or in spite of, its many layers and references, ultimately the work coheres. Tremble Tremble holds its centre and stands as an ambitious and multifaceted project. In the context of Venice it was timely and leading up to a critical stage in Irish social and gender politics it performed superbly. Now, viewed in an altered state, it is best read as a fable, hopefully one heralding a whole new era.