‘But still, like dust, I’ll rise’ (after Maya Angelou)

Curated by Vivienne Dick

Galway Arts Centre June 1st – July 6th

There have been various debates about what role a curator should take – from Robert Storr’s position of ‘exhibition maker’ to Rossen Ventzislavov’s view that a curator can create multiple meanings through their intelligent art selection, thematic concepts and spatial awareness, all of which contribute to new custodial narratives, adding conceptual layers to existing works and thus offering new meanings for the viewer. Vivienne Dick’s ‘But still, like dust, I’ll rise’ definitely falls into the latter. The root of this exhibition is the 1970’s as shown by the title, borrowing from Maya Angelou’s 1978 poem, a strident and sassy voice for oppressed women of colour to make their voices heard, to the inclusion of the seminal work by Dara Birnbaum, Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978-79). This period marks the start of feminist art history – spearheaded by Linda Nochlin et al, what followed was an art revolution in terms of media and subject matter which has now become the norm for contemporary artists of all genders.

The careful juxtaposition of intergenerational works creates aesthetics of space by repetition and cyclical flows, metaphorically alluding to the fragility and potential erasure of cultural and political gains, as well as the creation and destruction of the planet due to patriarchal systems. This phenomenological sense of becoming is unapologetically, affirmatively from a feminine root – a ‘strategic essentialism’ reinforcing the views of the influential feminist theorist Luce Irigarary, who like Dick has been addressing ‘the gender question’ since the 1970s. This authentic curatorial voice, embedded in the historiography of feminist art, gives the exhibition a powerful resonance.

Entering the Galway Arts Centre one is met by a monotonous, Irish female voice, droning constantly in the background. Always One on the Outside by Suzanne Walsh is a witty digital loop, a probing sensory reminder that gender is not a biological fact but a cultural construction, that language is learned and whoever is in power can create the marginal. There is an air of tedium about it, like the shipping news, presenting whimsical art snippets cut with empirical facts lending it an air of authority. In the first space on the ground floor Alice Maher’s exquisite Running Girl, a small bronze sculpture of a girl caught in the moment, hair blowing in the wind, gives the illusion of movement towards agency and freedom, and is placed strategically low so the viewer has to change their perspective to a child’s view. Small, robust but fragile, she is an iconic talisman of resistance.

Placed diagonally in the centre of the room, Eileen MacDonagh’s From Another Constellation also suggests continuums of destruction and creation. The heavy materiality of granite, appearing deceptively light by its smoothed surface, implies a universe in reverse. These regimented forms, shaped like fallen stars, diminish in scale and colour. Nodding to minimalism and its inherent masculine history, within the context of this exhibition and its relationship to the other works, it is a reminder that, irrespective of gender, all human kind is made of matter, as are stars.

An awareness by Dick of the language of materiality as well as art history is evident. Contrasting with these monumental materials, the walls are hung with more humble media. In Alexis Adler’s Cumus Corona Complex, a deceptively simple digital photograph denotes an in-vitro female egg, that magnified resembles a cosmos. Selma Makela’s mezzotint of an Iceberg and her humble painting in tones of yellowy greys depicting a deflated hot air balloon (entitled Lost Arctic Balloon) add an amnesic sense of poetic tragedy to human endeavours. This is further accentuated by Dragana Jurisic’s Noli Timere Mnemosyne V. Made from a light box, it requires close scrutiny by the viewer, who must peer into the lens to reveal a small figure splashing in the water. As the poet Stevie Smith might say, is she waving or drowning? Vivienne Dick’s hauntingly beautiful Red Moon Rising presents a floating world on the cusp of destruction. Conversing across space these works are full of pathos and ambiguity that open up many questions. What would happen to the universe if culture were framed from a feminine centre – would we be facing the ecological destruction looming under patriarchy? As power seems to be shifting towards the feminine, is there hope?

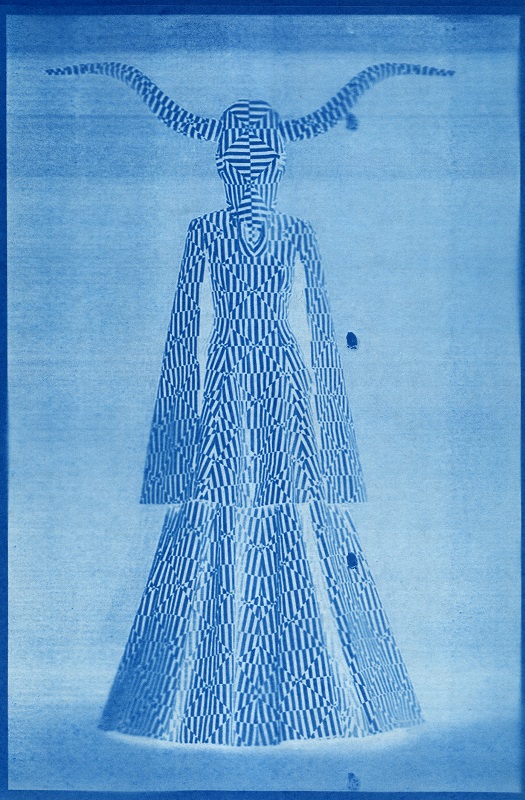

In the next space Dick suggests an alternative female universe, whilst continuing to humorously parody patriarchy. Breda Lynch’s The Goat Woman denotes an ancient and futuristic Goddess culture in bold, blue tones juxtaposed on the opposite wall by her wonderfully witty and ironic Cake Bomb and A-Bomb, where on the cover of Life magazine both the nuclear family and the H Bomb shaped like a tiered birthday cake poke fun at past ideologies.

The last work on this floor, Oscar by Olivia Eberstadt, a film made in 2017, is strangely reminiscent of an earlier aesthetic akin to Dick’s No Wave era. Entering through a curtain into a dark space, the spectacle of the moving image is an edgy and erotic black and white film, questioning queer/genders with the charge of knife on flesh, crowning and glittering the body politic.

In the upper gallery space, Dick has selected two more works by Maher which present multiple alternative views of how gender is controlled and constructed by culture. The fluid brown bold line of La Mujer Sierpa drawn on a fleshy background pink represents a figure of a Goddess, the Medusa, or an alternative Eve. Woman is presented as the life giver and taker, or Mother Earth. Here is an idea of a matriarchal world before Eve was blamed for the exclusion from Eden, and Humanity’s fall placing the guilt on women’s shoulders. This interest in hybridity and the nature/culture dichotomy is furthered in Hind, a beautiful watercolour of a fantastical creature half-female half-fawn, the tiny cloven hooves contrast with a raging distorted female face, both brutal and bold, like Paula Rego’s distorted females.

This repetition of artists’ work between spaces and themes, from the bottom gallery to the top, is furthered in Lynch’s looped video Fragments of a Lost Civilisation playing in the fireplace. The Endless Goodbye, by Kathy Prendergast, a black and white photograph of a hand caught waving, repeats a theme of temporality and mortality, brought together by Isabel Nolan’s poetically titled digital photographs Those glorious eyes grew faint in their sight, and I am Wonderfully and fearfully made. These emote a cold aesthetic. The titles are somewhat more impressive than the visual but the subject matter, of a sleeping medieval King and an urn give a strong narrative within the exhibition. The destruction of the world is what happens when good men do nothing.

The politics of the body and the continual struggles for women to negotiate within male perceived views of sexuality becomes heightened in the last room. Margaret Mairana’s large line drawing of her own nude body, which is strategically applied on top of Irish Independent newspapers, My Body is Not a Commodity a Self-Portrait: Intricacies of Blood and Bone Overlooked, is a strong work. The vulva placed strategically at eye level, a reminder that life is female-centred but cultural power and control of the body is still shaped by a patriarchal structure. The vulnerabilities and complexities of the politics of the female body, exploited by a male ideological system, are heightened in Dragana Jurisic’s work Trebvic, Bosinis (from YU: The Lost Country) series. As the head of a small girl looks to a horse there is a suggestion of the loss of childhood innocence and potential exploitation of women’s sexuality, which is contrasted with two stills from Dick’s 1978 films. These gave an alternative femininity of rage and attitude particular to the punk era which she chronicled extensively during her time in New York in the eighties, as new attitudes to gender and the stirrings of girl power erupted.

In this contemporary wave of #metoo celebrity feminism, where the ‘f’ word has been brought from the margins into the mainstream somewhat by Hollywood women exposing their exploitation within a system that is perpetuating an ‘ideal’ of femininity largely based on sexuality, the complexities of how it is controlled and by whom is reinforced by Birnbaum’s Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978-9). This radical deconstruction of the well-known 70’s TV series, vividly demonstrates that the questions asked then are still pertinent now.

The video explodes with meteoric light, and, as one writer notes, it was, ‘an incendiary destruction of the ideology embedded in television and pop cultural iconography’, Birnbaum isolates and repeats the moment when an ordinary woman, dressed in demure clothing, transforms into a super-hero, in knee high boots, a corset and shorts, an erotic vision of female sexual power for a male gaze. The disco beats of the song are also subverted in double entendres revealing the source of superwoman’s ‘supposed’ empowerment, her sexuality and how that conforms to a male ideal of the feminine. In light of the moment in which women now find themselves, particularly young women with the Kardashian culture pervading, it continues to raise questions as to whether sexuality is controlled by women for themselves or, by the patriarchy for whom the images of women constantly appearing in the media are mostly intended. How far have we come, how far have we to go?

Less than a decade ago many art historians and artists were less happy about being aligned to feminism than they are today. It is therefore refreshing to view an exhibition by an artist who has surfed the wave of feminism’s ebbs and flows and by weaving and integrating the work of intergenerational artists explores new narratives in a way that is visually poetic impactful and very much of the moment. Let’s hope Miriam Shapiro’s astute warning that, ‘Each generation opens the wound that closes in the night behind them’ is no longer relevant with this latest wave.