Miguel Martin, Let the Dead Leaves Fall at Millennium Court Arts Centre

This time of year does something to people, and worse – we’re all in on it. From every TV screen, Instagram post, billboard and glance in the mirror we are reminded of our untapped potential. Nothing is more addictive than speculating about who, where and how we could be, if only we would a) get off our arses, b) nurture our body and mind in ways that don’t involve substances, c) recognise and reach for our goals, d) be kinder and more proactive citizens.

The co-opting of positive mental health messages by the physical health crowd is increasingly prevalent and something that raises not a little suspicion amongst those, like me, who are actually pretty keen on options a) and b) above. I was quite poised to take issue with the two main themes of Martin’s work in this exhibition: spiritual worship and its gateway drug: yoga.

He’s not wrong, I am.

Here in his first multi-work exhibition, Martin elaborates upon what it was that first engaged me about his practice: deeply sincere research, delivered with tonal variations of light and shade. He describes the works as ‘textures’, which I think is beautiful. To me, they are more like cadences; love thyself, but not too much (the Supreme Being is always watching).

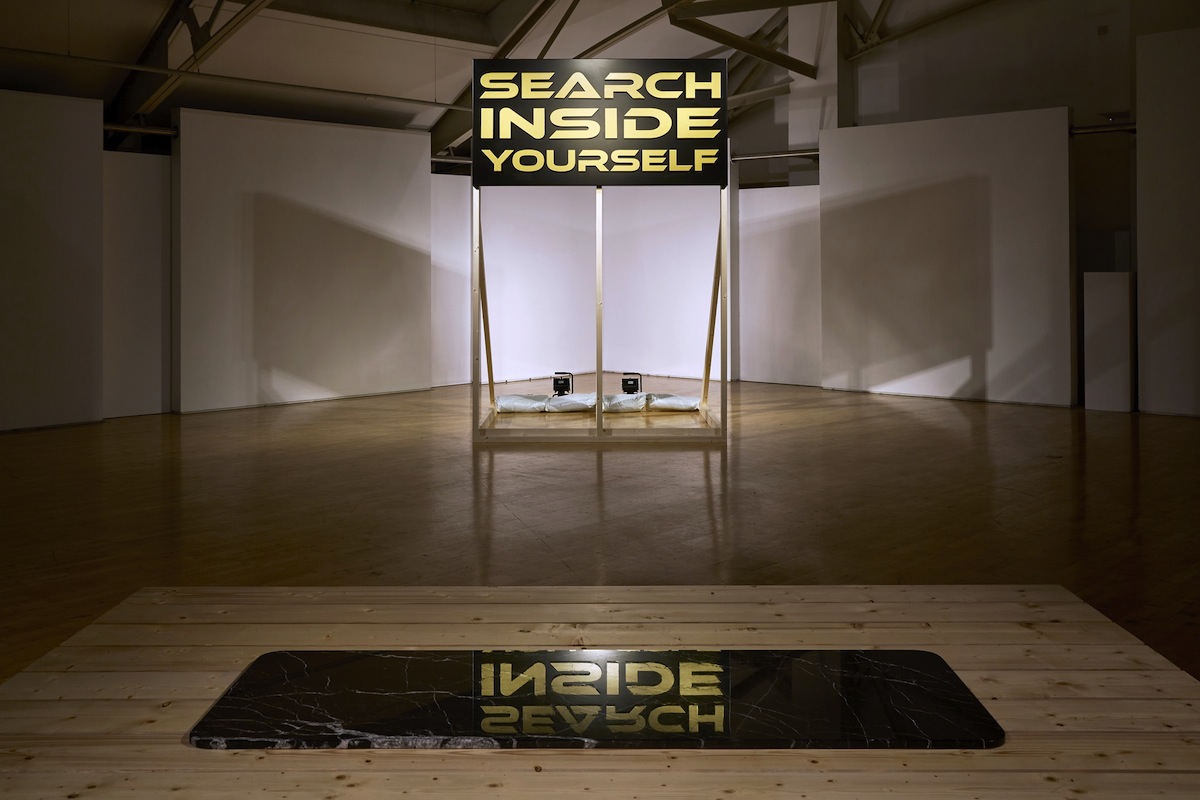

On that, Google’s missive to its workforce ‘SEARCH INSIDE YOURSELF’ – reproduced here by the artist in glimmering, muscular aluminium – is grounded in language designed to empower the individual to be – and do – better for the organisation. It makes me think of fist bumps all around at the keg party, or that film (long forgotten) where the shrouded villagers chant ‘the greater good’ in unison when threatened by outside influence. It feels ignoble to state that one of my favourite things about the show was the introductory vinyl text. Barely perceptible, in white on white, you genuinely feel a sense of reward for noticing it.

Perhaps it’s that ever so subtle white text that makes it gently apparent that this exhibition is, foremost, about language; the references to emotional labour, labour exchange and call and response. The aesthetics underpinning the works in the show, and the currency of those aesthetics more broadly, have been exquisitely homilized in a tract-like pamphlet by Brussels-based Irish curator, writer and artist Padraic E. Moore. It’s a lively counterpart to marbled surfaces, flickering candles and cavernous ceilings.

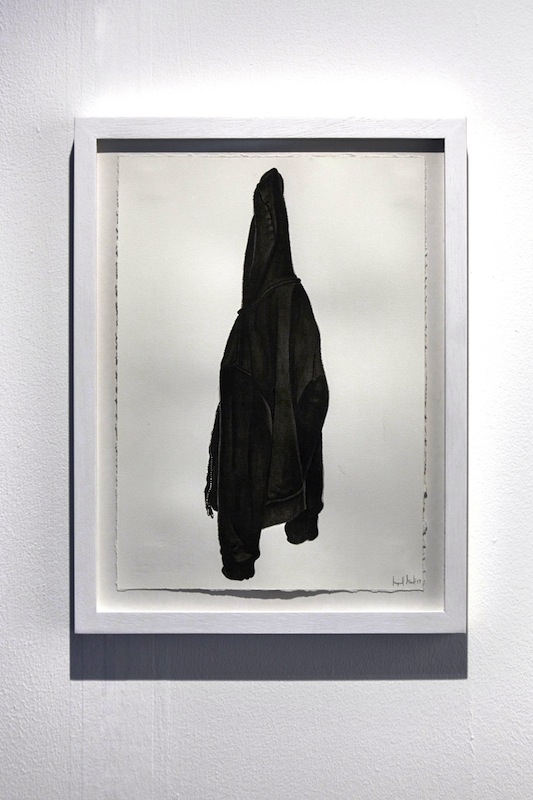

Whilst this collection of work thoughtfully – and mercifully – sidesteps what we in Northern Ireland consider ‘religious’ (i.e. green or orange), Martin’s expansive video piece, Downward dog not spiral, does certainly have undertones of The Disappeared on the beaches. Exercises depicted by a hooded Martin are shot in bursts of film that feel very much like trauma-induced flashbacks. His immaculately rendered and seductively lit ink drawings of sportswear – or robes, uniforms, vestments, signifiers, class distinguishers, barriers… disguises even – feel inextricable from Portadown – the place that is the ancestral home of the Orange Order, the stomping ground of masked paramilitaries every summer for more decades than Martin or I have been alive.

The rhythm of the exhibition is very much intended – and completely accomplished – by Martin. The lighting, enfilade and interpretive literature beckon us to follow this procession of objects-textures-cadences, until we reach a solitary bronze. Segregated and apparently silent upon its plinth, it speaks intelligibly only to those who recognise its code. The inference of gang signs or masonic handshakes is compounded by the sculpture’s rendering as an artist’s edition of 100: a series of gilded lapel pins. They’d probably glint beautifully from the rider’s lapel on his high horse as he passes you.