Is CIRCA an Artists’ Magazine? Part I

Writing in 2006 for the 25th anniversary issue of CIRCA, Anne Carlisle (co-founding editor with Christopher Coppock), looking back, traces the magazine’s genealogy:

“When I briefly recount its origins, you could be forgiven for thinking that Circa’s parentage was located somewhere in Berlin circa 1970, because Circa was the brainchild of the Artist’s Collective of Northern Ireland which in turn was the offspring of Art & Research Exchange (ARE), which was itself an offshoot of the Free International University, which had originated as a concept from amongst others the German artist Joseph Beuys.” [1]

In 1973, Joseph Beuys and Heinrich Böll wrote a manifesto for the Free International University, setting up the guiding principles of the school:

“Creativity is not limited to people practicing one of the traditional forms of art, and even in the case of artists creativity is not confined to the exercise of their art. Each one of us has a creative potential which is hidden by competitiveness and success-aggression. To recognize, explore and develop this potential is the task of the school.

Creation – whether it be a painting, sculpture, symphony or novel, involves not merely talent, intuition, powers of imagination and application, but also the ability to shape material that could be expanded to other socially relevant spheres.

The creativity of the democratic is increasingly discouraged by the progress of bureaucracy, coupled with the aggressive proliferation of an international mass culture. Political creativity is being reduced to the mere delegation of decision and power.

It is not the aim of the school to develop political and cultural directions, or to form styles, or to provide industrial and commercial prototypes. Its chief goal is the encouragement, discovery and furtherance of democratic potential, and its expression. In a world increasingly manipulated by publicity, political propaganda, the culture business and the press, it is not to the named – but the nameless – that it will offer a forum.” [2]

The influence of the Free International University led to the setting up of Art & Research Exchange in Belfast in 1978. Christopher Coppock, one of the early member and its first director in 1979, wrote about it for The Vacuum:

“Originally the organisation materialised and made its presence felt as the Northern Ireland workshop of the Free International University (F.I.U.) … The FIU, as its title suggests, had aspirations to become a global network of creative groups and individuals involved in interdisciplinary research and creative development; crossing boundaries between art and community, politics and economics, history and culture.

ARE was to be the FIU’s outpost in Belfast, and initially… the workshop operated as a standing conference, where events took place peripatetically; generating debate, agitating for bureaucratic change, and generally getting involved in ‘consciousness-raising’.” [3]

The Free International University and Art & Research Exchange brought to Belfast the polemics of conceptual and Socially engaged art. As Carlisle recounts:

“The debates emerging at that time argued for the need to examine art production within the context of sociopolitical realities and to investigate the relationship of art and artists to audiences both within and outside the conventional gallery space.”

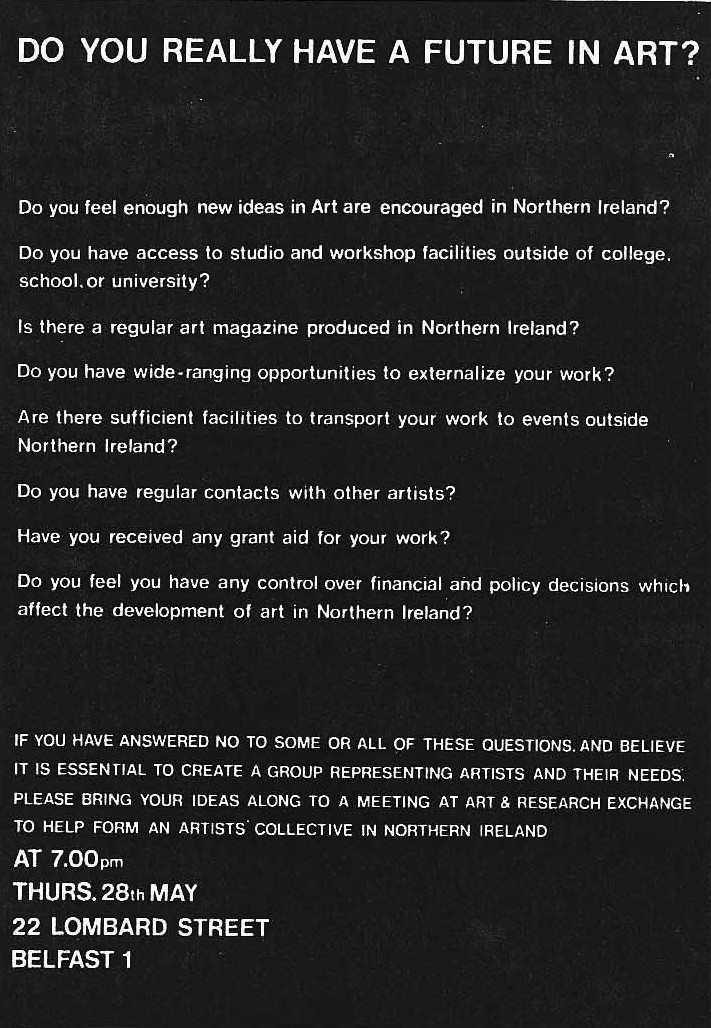

In May 1981 ARE sent out “a general invitation to the artistic community in Northern Ireland to attend a meeting to establish an artist’s collective.” Over one hundred artists responded to the invitation and the Artists’ Collective of Northern Ireland was established at that first meeting along with a manifesto.

“Which included … an intention to actively and critically comment on a range of financial and policy decisions affecting the arts in the region. This was coupled with a strong desire to enhance the artistic environment through the establishment of practitioner networks, studio and workshop facilities, alongside the aim of developing a wider-ranging cultural discourse, which it was generally agreed was undernourished and lacking in focus, but … could be remedied by publishing an art magazine with a critical edge.”

And as Carlisle and Coppock wrote in 1990:

“When the seed of a visual art magazine was first sown, optimism fuelled by collective energy signalled that change within the visual arts was possible.” [4]

This initial collective energy that accompanied the creation of CIRCA was cruelly missing when it went out of print in 2009, and few seem to care much for its demise. Yet the needs of artists, it seems, are not so different from the 1980s: they are still underfunded, struggling to avail of workspaces and yearning for sustained critical engagement with their work.

Thus there are some questions that readily present themselves: are publications – printed or online – the best remedy now, and do they still have the capacity to bring about a community beyond specialised interests?