Infrastructure and Vision

An Overview of the 38th EVA International, Ireland’s Biennial, 14 April – 8 July 2018

On 26 June 2018, two heavy black curtains separated the heatwave in the Cleeve’s Factory courtyard from the relentless sun in Soleil Double (2014) by Laurent Grasso (France). Throughout the film, the Esposizione Universale Roma (a Roman district built for the unrealized 1942 World Fair and intended to celebrate 20 years of fascism) is drenched, almost obliterated, in light. The sun blazes through the skyscrapers, saturating the terse astylar classicism of the buildings, their supremely rational arches, their curled-lip squared-off arcades. It is a perfect, unpeopled utopia, with the human scale represented by statuary – the whipped white marble of the carved robes on portrait busts viewed from behind, and the disinterested beauty of a full-scale sculpture of a boy, pointing loosely into the middle distance. A tree casts its asymmetrical shadow in the courtyard. In one frame, the camera pans across a shallow-relief frieze installed in one of the buildings, which includes the depiction of the huge operation to remove and reinstall the Egyptian obelisk (and sun dial) in the courtyard of St. Peter’s during the sixteenth-century renovations. A detail, and a historical leap, but the image of the men standing around the tall pole, trying to gently lever it into place so as not to snap the ancient, precious marble, brought to mind the well-known image from Ireland’s rural electrification scheme in the 1940s, reproduced on page 39 of the EVA catalogue, which shows five men carefully raising a wooden telegraph pole in a grassy field, directed by one man gesturing with one arm outstretched towards them.

Buildings. Empires. Light.

Grasso’s piece is a beautiful meditation on light, film and doubleness, but it seems to have a quiet punchline – the style is ancient, the stone is ancient, the ideas expressed aim for antiquity and permanence, but the light is older. The strange doubleness of energy – older than we comprehend, yet fleeting; vulnerable to human intervention while holding us at its mercy – runs throughout many of the pieces in the 38th EVA International exhibition, curated by Inti Guerrero, and produced and delivered by the excellent team in Limerick. When Need Moves The Earth (2014), a video installation at the Limerick City Gallery of Art (LCGA) by Sutthirat Supaparinya (Thailand), connects with these ideas about energy, beauty and temporality. Supaparinya’s three-screen installation represents the impact of the coal-mining and the construction of a dam on the landscape. This work – viewed from above in a perspective that creates the impression of a mythical scene – both expresses the seductive scale, heft and power of such projects (the noise, the ambition, the explosions, the earth moving under your feet), and the intense beauty of the interrupted earth (the textures and unexpected colours of the rubble, the striations of an exposed mountainside). You know you probably shouldn’t think so, but it’s impressive. It’s powerful. This is not a film about the undoubted negative impact on the ecosystem, or the lives interrupted during these projects. It is about the seduction of power. The seduction of infrastructure.

Have you ever felt like that about the M7 motorway?

Inti Guerrero’s decision to place Seán Keating’s Night’s Candles Are Burnt Out (1928-29) at the centre of the exhibition roots the 38th EVA in the artistic heritage of Limerick city (where Keating was born and received his first artistic education, as charted in the work of Dr Éimear O’Connor), as well as connecting this international biennial to a very local story – the development of the dam at nearby Ardnacrusha. This was, without a doubt, one of the transformational projects of the Irish Free State, requiring huge investment on the part of the government and the population. It required the citizenry still shaken by a decade of war, to allow themselves to become seduced by the image and promise of the future. The seduction of infrastructure is well expressed in the series of Keating’s works in oil and pencil in the first room of the LCGA, which has been painted a dusky red colour more reminiscent of the Hunt Museum than the white cube space visitors are used to in that building.

Like Supaparinya’s installation, Keating’s series of the Ardnacrusha dam scheme highlight the beauty of the work, with the concrete structures cast in a tonal and visual language more suited to sunkissed picturesque vistas such as the Castel Sant’Angelo. The paintings are beautiful, with dreamy tonal qualities that recall Singer Sargent or Turner, with just one black arm of machinery, densely and complexly painted, cutting diagonally across the ochres of the cut-up landscape. This work of ‘beautification’ is echoed and refracted in the series of photographs reflecting Li Xiadong’s (China) painting of the workers on the Three Gorges Dam (Hot Bed 1, 2005). The centrepiece painting itself, Night’s Candles Are Burnt Out, however, reveals a more ambivalent attitude to the emerging structure of the new state. Rather than simply making myth out of infrastructure, the painting bathes the strange, almost grotesque figures standing in front of the dam in a harsh, bright light, illuminating their faces, leaving them nowhere to hide. On the right hand side, a family group looks into the future, a small boy buries his hands in his mother’s hair as the father points towards their possible futures.

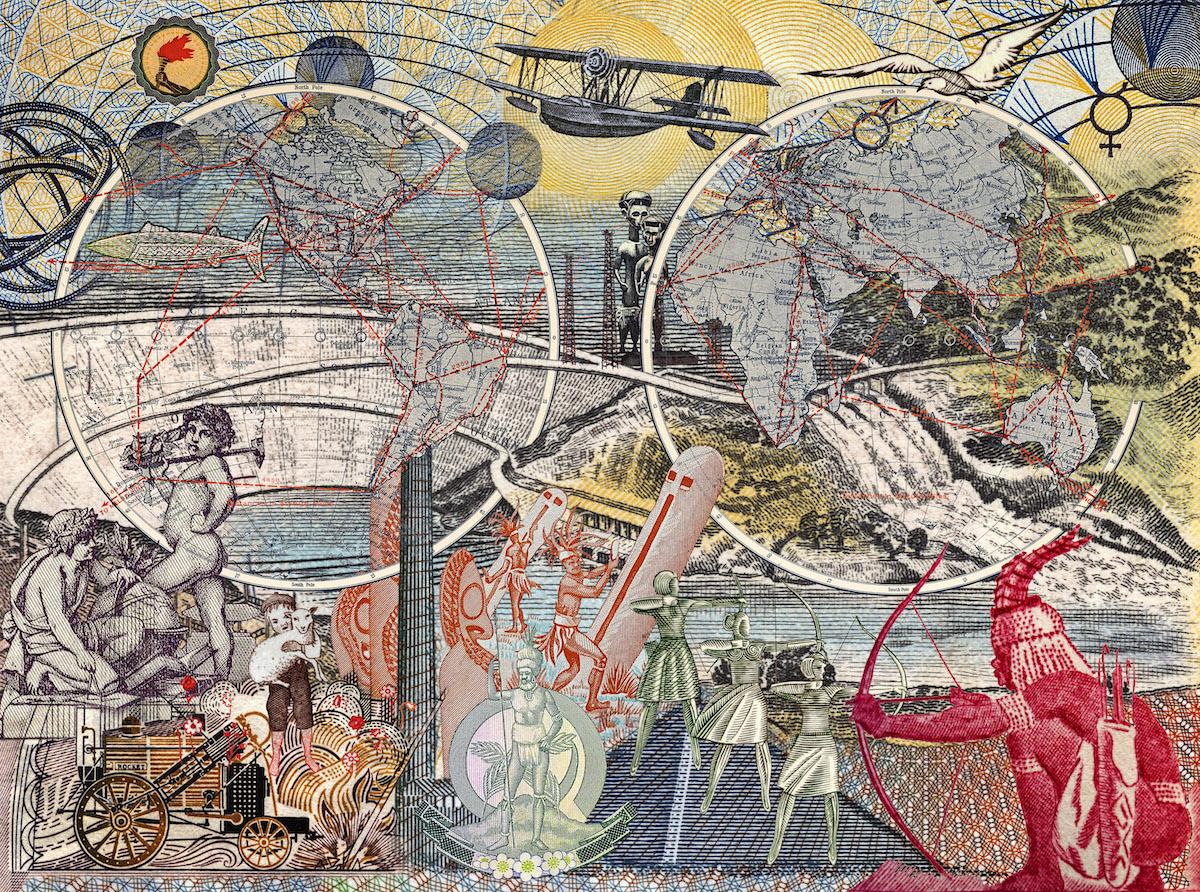

Infrastructure, as Sorcha O’Brien’s catalogue essay outlines, structures our lives yet remains, for the most part, invisible. It sends us this way, instead of that way, and after a while, perhaps we don’t notice that our path is being directed, as long as it is relatively comfortable. It’s turning on a light switch. It’s the black ribbon of road and bridges cutting through a patchwork of fields and mountains. Less comfortable – with a different hand of cards, it could have sent me (or you) to a Magdalene Laundry. A few different factors and a few decades later, it could send you (or me) to a border crossing with an inconveniently-coloured passport. If you are lucky, infrastructure is comfortably invisible. If you’re not, it must feel like an insurmountable maze. The 38th EVA troubles the role of art and visual language as ideological infrastructure – as something that can support its invisible function, and make it appear natural rather than made. Conversely, it can be the form that can roughen the smooth rhetorical structure, allowing infrastructural pathways and networks to become visible, putting the energy flows on the outside. As Joan Didion wrote in her essay on the Hoover Dam, published in The White Album in 1979 and included in the EVA catalogue, once seen ‘its image has never been entirely absent from my inner eye’. This idea of visualisation is beautifully articulated in the works on paper by Julie Merriman (Ireland) included in the LCGA, and in the collage pieces exhibited in the same room by Malala Andrialavidrazana (Madagascar). Andrialavidrazana employs the visual language of cartography, images of growing cities, armies, animals and ocean creatures, together with the kind of images of ‘colonial Others’ which might have populated the pages of a late 19th or early 20th century English travel book. They combine to form a visual map of rhetoric, of ideologies that enable some, and inhibit others, and are linked to the ‘Paddy and Mr Punch’ cartoons reproduced in the catalogue. These ideologies create infrastructure, which today can certainly take you there, not here; can take you to a coffee shop queue in Philadelphia, or to a police shoot-out in Philadelphia. Solange captures these infrastructures perfectly in A Seat at the Table when she sings ‘When it’s going on a thousand years/ And you’re pulling up to your crib/ And they ask you where you live again/ And you’re running out of damns to give’.

The diverse works selected by Guerrero for the ground floor of the LCGA respond to the particularities of the varied spaces, creating connections and building up layered meanings in a nuanced and subtle way. There are beautiful visual and tonal harmonies drawn between the Mainie Jellett (Ireland) paintings and Sutthirat Supaparinya’s video work, as well as between Jellett’s pieces and the geologically-inspired sculptures by Dan Rees (UK). The striking work by Uchechukwu James-Iroha (Nigeria) is given a room to itself, and the dark wall colour and careful lighting allows the images to slowly reveal themselves to the viewer. The idea of spiritual infrastructure is drawn out in the conversation between Jellett’s work and that of Bruce Connor (USA), a theme that is further developed in the Limerick Clothing Factory venue, where excellent use is made of the exposed wooden roof beams as a context for Colin Booth’s (UK) neon Jesus Wept (2012-13). Upstairs at the LCGA, individual works such as the enigmatic, voluptuous and abstract Mum (2014) by Patrizio di Massimo (Italy/ UK), and the photographs by John Duncan (N. Ireland) of the architectonic and sculpturally satisfying pallet piles ready to be set alight during 11th July celebrations in Northern Ireland, hold their own in a packed environment. Work as potent as the paintings by Rita Duffy (N. Ireland) simply requires more space, and ultimately this section of the gallery felt too small for the multiplicity of work and ideas being expressed.

The Limerick Clothing Factory is a welcome addition to the venues used by EVA, and extends the exhibition further into the city. This quieter, more meditative space housed Darn Thorn’s (Ireland) compelling images of post-1960s Catholic churches in Ireland unmoored from their suburban contexts and re-anchored in a surreal pastoral, as well as a series of pieces that engage with the female body and the histories of women and girls in different ways, from the shockingly violent #NoName (2016), the shrine-like structure in memory of Jyoti Singh Pandey by Marie-Claire Messouma Manlanbien (France) and Girl Interrupted (2014) by Peju Alatise (Nigeria), to the more structural ways that the female body is regulated, as in (Hair Headscarf (2016) by Mina Talaee (Iran), and Crisálida II (1998) by Patricia Belli (Nicaragua). In the courtyard at Cleeve’s, the visitor is compelled to crane her neck back and upwards to look at the magnificent, powerful Lady Rosa of Luxembourg (2001) by Sanja Iveković, but I also appreciated the careful positioning of Alatise’s Girl Interrupted above eye level, which leaves the viewer positioned below, out of the line of sight of the figure, a hapless supplicant of sorts to the inscrutable figure above.

As an exhibition that explicitly addresses the politics of the body, EVA had a lot to contend with this year. The visual noise of the streets became more and more intense as the referendum vote on 25th May drew closer, with increasing numbers of posters, banners, and demonstrations occupying public space. Complex, personal and deeply moving personal narratives occupied airwaves, social media pages and newspapers in the weeks that coincided with EVA. When the EVA team commissioned Emer O’ Toole to write the essay ‘I Wish Ann Lovett Were Out Buying A Swimsuit for Lanzarote’ for the catalogue, they could not have known that Rosita Boland would write a searching article on the Ann Lovett case in the Irish Times on March 24th, and that this would be followed up by a deeply moving interview with Richard McDonnell on May 5th, nor that the essay would strike an even deeper chord with readers because of this. Inti Guerrero, Matt Packer, and the whole EVA board and team must be commended for their resolve in ensuring that these most pressing, most relevant and raw issues of the contemporary moment were not wallpapered over as being too ‘difficult’ or ‘political’ for an art event that depends largely on public funding. Growing up in Limerick, I have long turned to EVA to help me make sense of the world – I did so this year, and I did not find it lacking. In this, I think that the 38th EVA built on and extended the legacy of 2016, and Still (the) Barbarians, curated by Koyo Kouoh. While Kouoh’s exhibition was able to engage in an elegant, assured, and often furious, debate with the idea of 1916 and its commemoration, the changing conditions of 2018 felt far more uncontrolled, a period of change that seemed to elude our grasp, or clear insight, until the very end. Still (the) Barbarians was a succinct, pointed reminder of what EVA could and should do, and the 2018 edition listened carefully.

And then you realise – my body (my self) is infrastructure here, like so many telephone poles.

One month following the landslide vote to Repeal the 8th amendment, visiting the rooms dedicated to the Artist’s Campaign to Repeal the 8th is a lesson in quick history. This dark series of small rooms in the Cleeve’s Factory site is dedicated to the campaign, including the ornate banners carried through the streets as part of the opening procession on April 6th, a series of videos from the Day of Testimonies held on 26 August 2017 (being read by Irish writer Marian Keyes during my visit), and a room which included press materials, the badges which became such an important part of the campaign, a shredding station with the remnants of pages of 8 on the floor, and the video footage of that important opening procession. It is important to see and have documented how Limerick artists and dancers (like Sinéad Dineen and Cut Out Dolls, Tanin Torabi and Isabella Oberlander) joined forces with figures such as Cecily Brennan and Alice Maher (to mention just a few) on the streets of Limerick to create a resonant, rooted procession and performance around the issue of women’s rights and bodily autonomy. Maher’s voice at the opening of the procession, in the grounds of the Art College (once the Limerick Good Shepherd Laundry) frames the video footage. Speaking about the women who had been incarcerated, she said that ‘we carry them the streets of the city from which they were banned’. In the post-Repeal sunshine, this archive stands as a testament to the intense labour that was required to make visible and make audible the legal infrastructure that constrained and endangered pregnant people in Ireland, and the work of undoing that infrastructural logic that had become sewn into our very skin.

A short review of an exhibition as capacious as EVA cannot do justice to all the participating artists, nor to the many different events, talks, tours, performances and the extensive outreach programme run in collaboration with Ormston House. The inclusion of Isabel Nolan’s (Ireland) work in one of the largest spaces at Cleeve’s deserves particular mention for its sheer beauty and impact in the space. Nolan’s recent body of work reflects the emergence of a group of artists that take an arch, almost playful approach to form and material, making it melt, swoon, swoop, bend in lush sculptural arrangements – in particular, I’m thinking of Nina Canell’s pliable neon tubes and Aleana Egan’s swooping metal curves, as well as Brendan Earley’s Styrofoam packing blocks that have been transmuted into metal. As ever, the catalogue is extremely valuable. It was released at the same time as the launch of the exhibition, which does mean that the images included do not reflect the Limerick context, and this is something of a loss. As an art historian who is deeply grateful for the presence of the archive of EVA catalogues, the fact that the majority of the pieces are not reproduced in colour also poses a challenge for future consideration of the exhibition. While cost is certainly an issue, perhaps something like an online set of images (available via the university or national digital archive and/or a body like Europeana) could form an alternative, making sure that these are accessible. This will enable researchers, artists, and curators to continue to draw from the presence of EVA (and its predecessors over the past 40 years in Limerick), aware of its role in negotiating the way that visual (plus) art can help us to make sense of the changing world around us.