Futures (in its current, second cycle) is described by RHA Director Patrick T. Murphy as “a series of exhibitions that attempts to anthologize emerging artists around whom a curatorial and critical consensus is beginning to emerge."

This is not the easiest thing to get right: consensuses can be wrong, particularly about contemporary art. Of course, that observation presupposes that there can be rights and wrongs in the aesthetic arena. In terms of aesthetic judgements, perhaps what is needed to establish the comparative worth of art objects is not ‘the test of time’ but ‘the test of fire’ – would ‘one’ really care if an art work was irretrievably destroyed, as in the Saatchi fire of 2004? In all the fog surrounding contemporary art, that thought-experiment could be a quick way to anticipate the judgement of posterity – which may well mourn the loss of the Chapmans’ work in the fire, and probably not that of Emin.

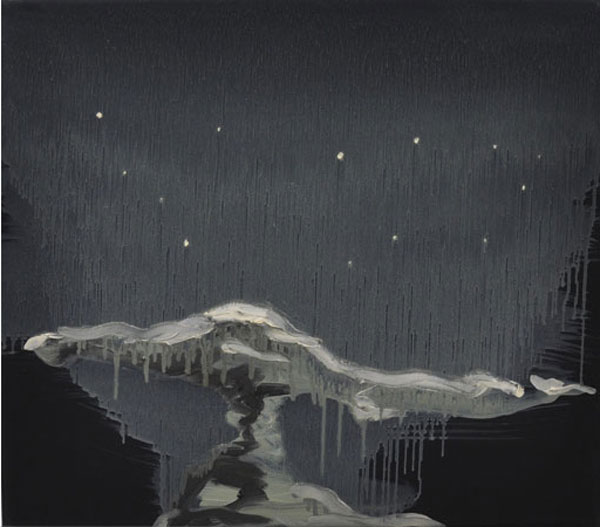

In any case Futures is quite diverse, ranging from the lush exoticism of Oisín Byrne’s large mixed-media works, and his photographic image of a sartorial event at Castletown House, to the starker oil paintings of Damien Flood, which eschew vibrancy with their use of washed out colours: white, brown, blue, grey, pink, black. The intricate drawing and sculpture of Niall de Buitléar (one of the latter pieces reminiscent of a ziggurat) contrasts with the video work of Rhona Byrne with its focus on the ‘physical sublime’ of roller-coasters and the enthusiasm of their aficionados – the work is more documentary than ‘art’, though admittedly the line is becoming increasingly blurred. The conceptualism of the work of Magnhild Opdøl in turn has little in common with the Internet-referencing work of Fiona Chambers, or the high-tech video/photographic pieces of Ailbhe Ní Bhriain.

The show is not completely devoid of cross-connections though: whether the return to drawing in Oisín Byrne and some of the well-accomplished drawings of Fiona Chambers, or the reference to animals by the latter (a somewhat awkward painting of the Ugliest Dog). Magnhild Opdøl’s work also focuses on animals, apparently referencing the relationship between life and death in the animal kingdom. Opdøl’s work also appears to be a wry, anti-Romantic commentary on ‘cutesy’ views of the animal world, somewhat along the lines already laid out by Mike Kelley (e.g., his ‘petting zoo’ in the 2007 Münster sculpture festival). The work has obvious resonances with the debate about animal rights and associated political concerns.

However, Ailbhe Ní Bhriain completely steals the show. Her cool, surreal, meditative works involving a combination of video, photography and music, and focusing on images of the sea and the countryside, are technically most impressive and provide a rare space for aesthetic contemplation. Her wall-pieces, involving a mixture of static and kinetic imagery, are somewhat reminiscent of the work of (equally high-tech) Irish artist John Gerrard, who has achieved widespread international recognition in recent years.