Heading out from Dublin to Cake Contemporary Arts to view …and if I listen in I hear my own heart beating…, Noel Kelly’s latest curatorial outing, one travels through a series of microcosmic landscapes, each of which forces drivers to revise the manner in which they operate their vehicles. One converts from the lethargic pace of city traffic to the confined velocity of the M7 transport corridor, and must then rapidly decelerate at the exit point so as to avoid obstacles on a meandering laneway that crosses a pasture full of sheep. Following this, open space and light abruptly disappear as the car dips into the shadows imposed by a stand of trees. Emergence from the wood places one in the peaceful surrounds of a country village. The impression, though, is but a fleeting one. Entry into the gallery building – what was once the Presbyterian Soldier’s Institute in the Curragh Camp – re-immerses us in the urban realm. The simultaneous wail of a siren and pounding beat of loud rock music emanating from an unseen place not only shatter the calmness, but also represent the coincidence, consequences and complexity of city life.

As juxtapositions go, the contrast is a brash one. The audio introduction not only clashes with notions of rural retreat and military orderliness, but also underscores a sense of urgency connoted by the readout that pulses across the acidic-toned map in the gallery’s press information. This aural backdrop – or soundtrack – disrupts or lends atmosphere to the viewing of works in Cake’s ground-floor space. Either way, the spillover effectively dispels the reverential aura prevalent in many galleries. But more importantly, it complicates an already complex set of visual structures by adding an abstruse aural veil that instills a sense of restlessness and feelings of anticipation in the viewer.

Niamh McCann’s large wall painting, the fêated (2010), is the first work to come into view. Despite its location on a far wall, the image declares its presence by virtue of its scale and central position. The subject also catches the eye, as this hybrid image merging space exploration and holidays at the beach juxtaposes Buzz Aldrin’s lunar walk with a woman and duck to create a curious vision of moon, sea and sand. The pairing of the celebrity / hero and scantily clad woman points to advertising clichés, an arrangement that on closer inspection fails to make sense. The inclusion of real and depicted reflective elements – gold leaf affixed to the wall and the visor of Aldrin’s helmet – bring viewers into the scenario. This tactic instigates a cycle of projection and reflection by casting us as directors and consumers. Seen from this perspective, the image references the mediation of leisure, landscape, history and adventure – images intended to inspire, but which must also meet people’s expectations.

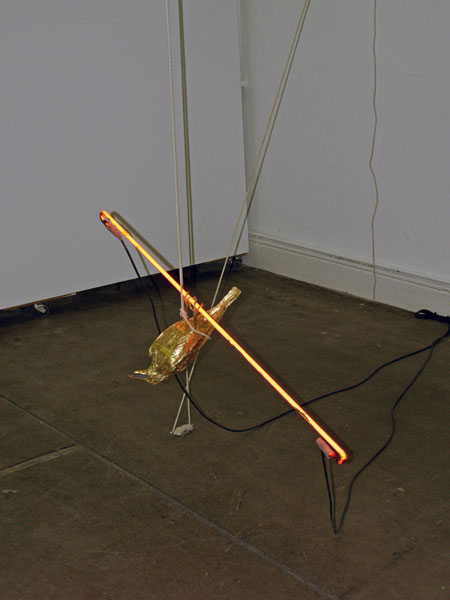

Around this work, contributions by Miha Štukelj and Fiona Mulholland, the remnants of a performance and a second work by McCann embody immateriality, aerial structures, transience and the force of gravity. In the drawing Docklands (2008), Štukelj reduces a Dublin industrial setting to a permeable, near-abstract web of contours fixed within a grid. On the opposite side of the room Mulholland’s Sans Souci (2010), a garden of corrugated polycarbonate that transmits and reflects light, rests precariously on overhead guy wires. Between these two works, bits of floor-bound hair from the opening night haircutting session and McCann’s The Golden Calf (2010), a zigzagging specter of the economy that culminates in an upside-down and gilded bird clutching a neon tube, speak about descent, impermanence, vanity and the intertwined processes of loss and renewal.

Following the trail of sound takes viewers to a stairway leading to Cake’s lower level. At the base of the stairs they find a blank, flat-screen TV resting on a pedestal that intermittently springs to life with Mark Clare’s Remote Control (2010). Accompanying the sudden blare of an air-raid siren is a video of a man on a bicycle pulling a large blue box in what seems to be a routine to which no one responds. The oddness of the activity slowly makes itself apparent. The siren not only drowns out all other sounds, but the intensity of its wail also never changes, even as the cyclist rolls out of view. Beyond Clare’s work, the run-down appearance of the red hallway, plus the loud sounds emanating from unseen places, call for exploration.

The journey bestows an intriguing and slightly disorienting air of not knowing what or where things will be found. In searching the level’s dimly lit environs, doorways that don’t open, cast-off goods and odd, empty, closet-size compartments are encountered. One compact space houses Alan Phelan’s Ciao No More (2010); in another S. Mark Gubb’s Stranger in a Strange Land (2007) is found. In this situation, the works come across like chimera. The ghost-like presence of Phelan’s superimposed factory images and nerve-rattling sounds of the assembly line complement the dancing light trails and deafening musical rhythms engulfing Gubb’s dark streetscape. They recall the failure of once-thriving industrial centres, anxious places where people, now lacking opportunities, feel isolated and live in surroundings where buildings exist in states of disrepair or collapse. The poorly maintained character of the exhibition setting reinforces the tension conjured by the video footage. Moreover, the hard surfaces of these otherwise empty chambers intensify the dissonance of the mechanical shrieks and aggressive rhythms accompanying the two videos.

Pushing back a heavy black curtain that has been suspended across one doorway reveals a large L-shaped room showing three investigative short films, the spirits of which assume an increasingly sinister air as we move from one to the next. The Lobbyists (2009), for example, features a wealth of factual segments from the administrative headquarters of the European Union. But Libia Castro and Ólafur Ólafsson’s depiction of Brussels’ invisible actors takes some pretty odd twists and turns. It delivers statements that accuse the supporters of transparency of engaging in voyeurism and describes the lobbyist as the James Bond of the legislative system. The production also subjects viewers to an incomprehensible report on photovoltaic cells. The film seems authentic to anyone giving it only half their attention. A focused ear, though, lets one revel in the mockery, especially the reggae song delivering a list of law firms, NGOs and government reps – a veritable smorgasbord of who meets whom for the purpose of influencing legislation.

![Marie Voignier: Un Minimum de Preuves [A Minimum of Evidence], 2007, video; courtesy Cake](/wp-content/from VAC/reviews/2010/images/cake/MarieVoignierDetail.jpg)

The mixing of reality and falsehood takes an uneasy turn in Marie Voignier’s Un Minimum de Preuves (A Minimum of Evidence) (2007). In this engrossing filmic guide to building a criminal case, unexceptional urban locations form the backdrop to a bureaucratic step-by-step process that ultimately leads to an unexpected conclusion. Compared to Voignier’s inverted symmetry and the blasé countenance of brutalist architecture, Alina Abramov charts a symmetrical journey through the bleakest of cityscapes that avoids crossing any political barriers. Filmed through the windscreen as the vehicle drives from night into day and day into night, Checkpoint Guilo, Jérusalem Juillet 2006 (2006 – 2007) offers a limited view of the city that takes one along high fences, through a tunnel and a relatively deep man-made trench. The enclosures along the route make it impossible to view what surrounds it. Though the trip is boring, the film nevertheless exudes a palpable tension. When, at midpoint, the vehicle encounters a barrier and makes a U-turn, expectation turns to disappointment. Arrival at the intersection where the journey started proves disheartening. An air of injustice pervades the space, especially when it is clear that the sky we all share resides directly above the unseen driver.

Noel Kelly has described the exhibition as a personal view of the city through certain symbols that convey familiarity and discomfort. As such, it successfully depicts an extremely complex place in which events overlap, interruptions abound and all types of noise penetrate space. Its open perspective, though it predominantly limits its references to Western cultures, incorporates a broad range of topics. The range extends from Utopian planning initiatives, as represented by Fiona Mulholland’s floating garden, to the oppressive bleakness of a society locked in the grips of religious, racial and political strife. Between these poles, one encounters all kind of brouhaha, the impact of which is boosted by the unrefined qualities of the space. From the uneven wood floor with its accumulation of hair clippings to the peeling paint of the lower cloisters, the venue underscores the edginess and frailty evident in the work. It also suggests evolution and impermanence. One could go further by proposing that the inherent grittiness of the building imparts credibility, for it is hard to imagine an installation of this scope, which manifests anxiety through multifarious energy and impulses, making the same kind of impact in the clinical context of the white cube.

The choice of location for the exhibition also surprises. Set in an historical building situated in a military camp well away from any urban centres, the project’s focus initially appears misdirected by conflicting with its larger setting and addressing an audience that might not appreciate it. But the issues of which it speaks affect nearly all of us at one time or another. Moreover, links with the community have also been forged. The stridor of the camp’s own siren, for example, occasionally penetrates the atmosphere and establishes rapport with Clare’s Remote Control. The presence of the camp’s barber, who offered free military-style haircuts at the opening, formed another bridge. In an extension of this performance Noel Kelly engaged in act of reciprocation. On the day of my visit to the gallery, he called on the barber in his shop and had his look renewed.

Like Abramov’s film, the trip back to Dublin mirrored the one to Cake. But the mind, temporarily resettled in the countryside, no longer thought about what lay ahead. Sifting through the residues of what had just been witnessed, it had become sidetracked with the desire to classify ideas and impressions, to apply order to a show fraught with multiple perspectives and a host of dissimilarities. The realization that cities are anything but rationally structured gradually emerged from this process. Codification of such highly diverse entities involves wrestling with chaos. The only thing to which we can cling is the course of observation, that sequence through which the experience unfolds and, in retrospect, coalesces into an incontrovertible whole. It forms an imperfect, yet poignant, narrative that takes risks. In pulling viewers out of their comfort zone, some will be energised by the proceedings, others will be enervated. In retrospect, the exhibition’s countryside setting suggests maneuvering. The purpose: to intensify its impact. But it is hard to quibble with a project that offers so much consider.