One of the peculiar developments in our Western world is that we are losing our sense of the divine side of life, of the power of imagination, myth, dream and vision. [1]

Francesco Clemente rarely presents an image of the complete human body; in this show, we find a pair of eyes, feet walking on feet, a hand with a bird in it. The bodies inhabiting Clemente’s most recent works are fragmented and anonymous, and if one were to stitch all the pieces together, the resultant image would still not reveal a picture of wholeness. Watercolours are laid onto paper with the lightest of touches, and the subject matter in the large oil paintings is ephemeral and mysterious. Images of violence appear occasionally, intermingled with clouds and pierced hearts, and empty palms suggesting loss. Humanity finds a fractured reflection of itself in this work.

|

Francesco Clemente: Recuerdo, 2003, watercolour on paper, 61 x 45.7cm, Photo credit: Greg Fuchs, image courtesy IMMA |

This fragility is perhaps what Ettore Sottsass was referring to when she talked about Clemente’s marking of “uncertain states" [2] in her essay, Francesco: libertine of mysteries. She mused in this essay that in life, “perhaps there are only these flimsy bits of paper, this paper that costs nothing, this flying paper, this paper that settles on your hands like dust," [3] and resisted reviewing his work in the traditional, critical essay form, preferring to approach his work from a more lyrical perspective, through a colourful, literary meditation on paper.

And paper does indeed seem to be a pertinent starting point for a discussion on Clemente’s work. One’s attention is constantly drawn to the material qualities of paper; the ease with which it is blown away, the ease with which it crumbles and tears; the way Clemente’s watercolours bleed into its texture. Paper is the perfect medium for the mystic concerned with re-enchanting every day life, for it is simultaneously the material of the prayer scroll and the shopping list; and it is immediate.

You only need a scrap of paper for a few words of love, only a scrap of paper to write down songs. [4]

|

| Francesco Clemente: Ginsberg’s Haiku, 2002 watercolour on paper, 45.7 x 61 cm, Collection Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, Photo credit: Greg Fuchs, image courtesy IMMA |

Such scraps of paper are depicted in Clemente’s watercolour, Ginsberg’s haiku, 2003; a sealed envelope with seven blank pieces of paper beside it. Delicate red and yellow washes describe the crisp edges of the paper. The title perhaps alludes to the poetry that could feasibly be inscribed upon it – or the seemingly random way in which a Ginsberg haiku is composed. What the scraps suggest is words or elements being scattered on the table to produce a poem, personal as a letter. Reading Ginsberg’s poetry is an interesting way to access meaning in this exhibition by Clemente; Four haiku, 1955 [ 5] , offers us brief glimpses of life akin to the scraps of paper shown in Clemente’s painting, and is equally as fragile; like shreds of paper, inclined to disappear or blow away. Momentary.

I didn’t know the names of the flowers – now my garden is gone.

Ginsberg and Clemente have collaborated together in the past, and the artist’s keen interest in beat literature is evidenced throughout his work. One of Clemente’s projects was the establishment of Hanuman Books, a publishing house in Madras, set up to publish beat writing, artist’s writings, and mystic texts. Literary interests populate this show not so much in text, but in a visual poetry that reflects the kind of imaginative free-associative thinking inherent to beat writing. The process of connecting ideas and images intuitively and playfully, as a means to access more mysterious and subtle realities, is one used by writers like Ginsberg. Connections between ideas made in this way are tenuous, yet potent because emotionally informed.

|

| Francesco Clemente: Honey and Salt, 2002, oil on linen, 205.3 x 157.5 cm, Collection Gagosian Gallery, New York, Photo credit: Robert McKeever, image courtesy IMMA |

In Clemente’s work the process exists visually. Gaps between different works are most appropriately closed using the free associations of a playful mind. Intuition is a better guide to this work than rational analysis. In the oil painting Honey and salt, 2002, we are offered an immersive, sensual experience. The flavour evoked by the title combined with the faintly outlined mouths, ambiguously painted one over the other, insinuates that one might taste the work as well as see it.

|

| Francesco Clemente: Silver and Stone, 2003, watercolour on paper, 61 x 45.7 cm, Private Collection, Photo credit: Greg Fuchs, image courtesy IMMA |

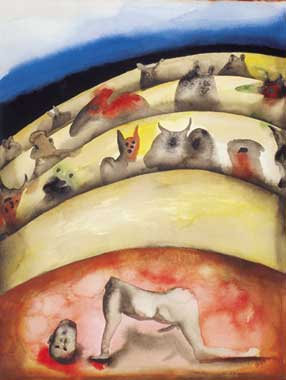

The blind, honeycomb eyes crying their single, golden tear stare from the canvas and lead one to wonder how/if they are connected to the dark eyes weeping silver tears in watercolours in the next room; or for what it is that they cry. The suggestion of honey connects the image to a huge cultural legacy of spirituality, mythology, and medicine; and to more recent cultural expressions of these legacies as exemplified by artists like Beuys and Laib, who have taken the significance of the actual material, honey, to create meaning in their work. There is a hand reaching for a ring with a ruby in it that bleeds red pigment all over the page; there are hoops of flowers (Warrior’s amulet, 2003) and animal/people lovemaking on all fours. Honey and salt is not alone in its sensuality within this show; this collection of work proliferates with birds, honeycombs, broken hearts, and obscure symbolic references which can often be read erotically, and which evoke physical as well as visual sensations.

|

| Francesco Clemente: Warrior’s Amulet, 2003 watercolour on paper, 61 x 45.7cm, Private Collection, Courtesy Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, Photo credit: Greg Fuchs, image courtesy IMMA |

In the last room which one encounters stand two immense oil paintings, Heart’s cave and She-snake . In Heart’s cave a large, heart-shaped piece of honeycomb glows golden and yellow, offering glimpses into its many-chambered interiors. The chocolate darkness around it locates the heart within some deep, unreachable place; cave, chest, tomb. This speaks of the very meaning of mystery; the dictionary definition of which is “a religious truth that one can know only by revelation and cannot fully understand." [6] Ginsberg’s poetry offers an irresistible description of this painting;

Holy are the visions of the soul

The visible mind seeks out for marriage,

As if the sleeping heart, agaze, in darkness,

Would dream her passions out as in the Heavens. [7]

|

| Francesco Clemente: Heart’s Cave, 2001, oil on canvas, 264 x 264 cm, Collection Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, image courtesy IMMA |

The honeycomb with its dual references to human flesh and the residence of bees speaks of the interconnectedness of all living things; it relates the human heart with its cavities, ventricles, and romantic associations, to the empty honeycomb with its deserted chambers, and the free association of bees and honey. The entire image is a culmination of poetic ideas that connect spiritually, and illogically, suggesting meaning without being prescriptive.

|

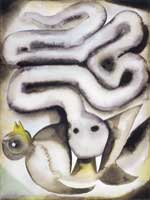

| Francesco Clemente: She-snake, 2001, oil on canvas, 264 x 264 cm, Collection Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, image courtesy IMMA |

She-snake presents an image that on cursory glance appears to be a phallus, yet on further inspection reveals itself to be an interestingly framed image of a she-snake shedding her skin. Her body rises upwards through the centre of the canvas, discarding her old skin around the bottom of the painting. The hexagons in the patterns on the shedding skin visually relate the work to Heart’s cave, alluding to the interrelatedness of living things inherent to spirituality or shamanism. It is easy and inspiring to ponder the mythical references to bees and snakes, to healing, medicine, and magic, which are presented loosely with this work; and it is precisely this kind of cross-pollination of imagery that makes Clemente’s show so fertile.

|

| Francesco Clemente: Time, 2002, watercolour on paper, 45.7 x 61 cm, Private collection, courtesy Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, Photo credit: Greg Fuchs, image courtesy IMMA |

The keys which hang in the tree in 5 steps connect to the keyhole in Anima mundi; the birds in the tree speaking to the birds in the tomb in Dialogue are similarly part of the reflection on mortality taking place in Time, where we see a hand with a bird held up, and then an empty hand. Allowing the mind to play with the gaps between the works, as one might write a poem using the free-association method, one is able to find rich meanings that are hard to articulate; relationships that are difficult to name. This way of thinking allows one to “foster psychic mobility, opening oneself up to a range of visionary experiences in a culture whose mindset has made the very idea of other worlds unthinkable." [8] The work is thus positioned within the discourse that defines the role of the artist as a shamanic, spiritual one. “The shaman does not live in a mechanical, disenchanted world, but in an enchanted one, comprised of multiple, complex, living, interacting systems." [9] This exhibition is antidote to a world made rational; a place to refuel the senses. It speaks to the heart in a profound way about what it feels like to be alive, senses and mind flung open to all the colours and creatures of this Earth.

|  |

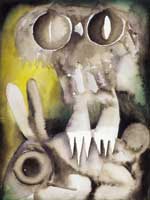

| Francesco Clemente: The Third Eye, 2003 watercolour on paper, 40.6 x 30.5 cm, Photo credit: Greg Fuchs, image courtesy IMMA | Francesco Clemente: The Third Eye, 2003 watercolour on paper, 40.6 x 30.5 cm, Photo credit: Greg Fuchs, image courtesy IMMA |

Central to experiences of vibrancy in life and concepts of the mysterious, is the contemplation of death. Confronting our mortality simultaneously makes us more fragile and more alive. What happens when we die is the ultimate secret, and Clemente explores the complexity of death in his watercolour series The third eye, 2003 . Fangs and claws radiate the raw whiteness of the paper beneath, in exaggeratedly savage depictions of a predatory snake, bear and owl, all keenly alive. The rendering of the prey in their mouths and claws, by contrast, is muted, and soft, as though the killed bird, mouse and rabbit have surrendered the vitality of life to the dark secret, the veil, of death.

|

| Francesco Clemente: Dialogue, 2001, oil on canvas, 203 x 203 cm, Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, image courtesy IMMA |

The immediacy with which the watercolours seem to have been captured reflects Clemente’s comprehension of the preciousness of a single moment. “Life is a fragile, gentle, uncertain thing…like cheap paper it drifts here and there." [10] Fragments of meaning, recognizable forms encountered as one finds images within a dream, these are haunting images that, even when described, read like a poem:

A tree of broken hearts, a tomb of birds, a hand that reaches for a ruby, urns full of leaves, faces obscured by clouds and starfish, dark eyes crying silver tears which become dark stone, a serpent with a duck in its mouth, clothes on a line that, hung together, resemble a person, and playing cards stacked upon one another with the sky behind.

|

| Francesco Clemente: Prophesy, 2000, oil on canvas, 203 x 203 cm, Private collection, New York, Courtesy of Kim M. Heirston Advisory, image courtesy IMMA |

Even when they exist only as language, these works retain some of their potency because they have been created with a literary awareness. Clemente’s work speaks the language of myths and symbols. It has a way of threading meanings together that plays with rational and non-rational aspects of visual and lingual languages. Bring a book of beat poetry with you when you visit the show, because its words will help you to access the soul of this work. If you don’t care for the beat poets, a shred of paper will do; if only to hold in your pocket, if only to inscribe with a thought and tie to the branches of a prayer tree.

|

| Francesco Clemente: Five Steps, 2001, oil on canvas, 203 x 203 cm, Private Collection, courtesy Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich, image courtesy IMMA |

Felicity Ford is an artist and writer based at the moment in Killiney;she is currently involved with the installation of her sound-works in the end-of-year DLIADT graduation showcase, and is working with arts-and-theatre collective Spacecraft on their current production, Bleeding the System.

[1] Gablik, Suzi, “Learning to Dream," The Re-enchantment of Art, New York, Thames and Hudson, 1991, pg 42

[2] Sottsass, Ettore, “Francesco, Libertine of Mysteries," Francesco Clemente: Three Worlds, New York, Rizzoli International Publications 1990

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ginsberg, Allen, “Four Haiku," Collected Poems 1947 – 1985, London, Penguin Publishers, 1987, pg 137

[6] http://www.m-w.com/cgi-bin/dictionary?book=Dictionary&va=mysterious&x=0&y=0

[7] Ginsberg, Allen, “Psalm II," Collected Poems 1947 – 1985, London, Penguin Publishers, 1987, pg 21

[8] Gablik, Suzi, “Learning to Dream," The Re-enchantment of Art, New York, Thames and Hudson, 1991, pg 46

[9] Ibid.

[10] Sottsass, Ettore, “Francesco, Libertine of Mysteries," Francesco Clemente: Three Worlds, New York, Rizzoli International Publications 1990