|

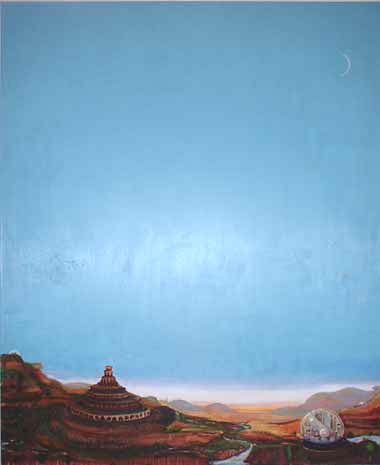

| Verne Dawson , Celestial Atlas, 2002, oil on tabletop, 51 x 51 cm, image courtesy the Douglas Hyde Gallery |

I have flown to star-stained heights on bent and battered wings, in search of mythical kings…sure that everything of worth is in the sky and not the earth… 1

The vast open skies of Verne Dawson’s paintings lying open, wide and light-filled, recall the heavens in Dory Previn’s Mythical Kings and Iguanas. Previn’s song laments mankind’s infamous obsession with finding meaning in stars, tarot cards and other mystical systems, at the expense of experiencing physical existence on earth. One could be forgiven for initially interpreting Dawson’s work as being inclined to do just that: skies dominate the show. For example, in Sunrise, an intense, cadmium-yellow orb rises through swirling blue waters into warm, puffy clouds. The painting was executed between 1993 and 1999, and over time Dawson has marked it with layers of oil glazes, so that the entire work glows with light like the sun at its centre. Lilac and yellow clouds are delicate and thin as chiffon and tiny threads of gold run down through the sky towards the ascending sun. It is the earliest work by Dawson in the exhibition, and uses the time of day, sunrise, as a metaphor for the beginning point of existence. The water in the painting represent the primordial ocean from which all life was born, and the image attempts to capture a sense of genesis. It speaks the visual language of religious ecstasy. The moment of our origins is treated reverentially; the words of science and the bible are translated faithfully, as the truth. Dawson explains his obsession with skies like this;

It’s an appreciation of man’s place in the world, in the universe and in nature. We’re so human-centric at this point in time that we’re not terribly aware of things outside of human activity, whereas in the past people were forced to realise their tiny stature in the universe. Now it’s as though the universe is hardly there and the bigger picture has been lost. I wanted to make pictures that were really about the bigger picture – painting is about the bigger picture. 2

So although the work initially seems to be about escaping where we are on earth through a preoccupation with the sky, it becomes clear that such a reading of Dawson’s paintings is inaccurate. Another agenda is present; one which searches for our inclusion in patterns and schemes that are larger than us. Previn’s song is positioned within the feminist critique of religious idealogies that privelige mind over body, heaven over earth, and spirituality over sexuality. She laments how this duality of doctrines deprives reality of its fullness, and yearns to replace it with a different belief system that unites the realm of ideas with physical experience. Perhaps Dawson’s unique version of star gazing represents just such a belief system?

I have ridden comet tails in search of magic rings to conjure mythical kings, mythical kings… singing scraps of angel-song; high is right and low is wrong;I never taught myself to give down, down, down… where the iguanas live. 3

What does it look like down where the iguanas live? Do Dawson’s paintings show us? Or is their preoccupation with mystical things part of the dualistic religious thinking which Previn criticises? Previn sings about her search for meaning;

…astral walks I try to take… I sit and throw I-ching… aesthetic bards and tarot cards are the cords to which I cling… 4

|

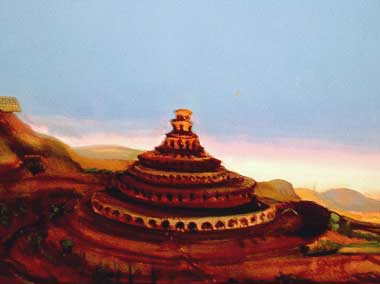

| Verne Dawson , Earthly Paradise (community House with utilities dome and examples of dematerialized human transport,) 2003, oil on canvas, collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg, photo credit: the author, image courtesy the Douglas Hyde Gallery |

Certainly it would seem that Dawson investigates similar systems to derive a sense of spiritual meaning or purpose for mankind, and uses such information to inform his work. But though he looks to the firmament, numbers, and mythology, it would be a mistake to say that Dawson is not concerned with the Earth. In Earthly Paradise (community house with utilities dome and examples of dematerialized human transport), 2003, a massive arc of twilight blue rises over a futuristic landscape; it is spacious and the only inhabitants are birds. The dematerialization of transport referred to in the title manifests as a complete lack of roads. Instead of using cars, buses or trains, people travel star-trek style through the air, showing as tiny blips of light in the blue. It is a utopian vision of the future, yet it also references the past with its undeniable allusion to Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delight.

|

| Bosch, Hieronymous, The Garden of Earthly Delight, c. 1504, Oil on panel; Central panel, 220 x 195 cm image held here |

Like Bosch’s painting, Dawson’s Earthly Paradise has domed, futuristic buildings in it. One of them also resembles Bruegel’s Tower of Babel, 1563, so there is a sense of future and past coexisting in the image. This happens a lot in Dawson’s work. There appears to be a quest to explore time in a non-linear way. Dawson says that this futuristic painting is;

…an optimistic fantasy of how we can return to some place where we have greater integration with the natural world and yet have an advanced technological society. I don’t advocate us returning to the caves and becoming savages again. I advocate a different relationship to nature, an awareness of cyclical time as opposed to a purely linear time, and a sense of responsibility to our environment is key to that possibility of a renewal. 5

|

| Image Detail: Verne Dawson, Earthly Paradise (community House with utilities dome and examples of dematerialized human transport,) 2003, oil on canvas, collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg, photo credit: the author, image courtesy the Douglas Hyde Gallery |

Another duality is contested; technology and ecology co-exist in Dawson’s vision. He also links the intimately close to the unimaginably distant, seamlessly, in his book, 432. This artists’ book was published in conjunction with the exhibition. This book reflects upon the ubiquity and significance of the number 432. It begins by stating;

A healthy, athletic adult at rest has a heart rate of 60 beats a minute.

60 beats x 60 minutes x 24 hours = 86,400 beats, that is 43,200 beats per day and 43,200 per night. 6

and towards the end, points out that;

The diameter of the sun is 864,000 miles (2 x 432,000).

The diameter of the moon is 2160 miles (4320/2) . 7

In this way, he links the most intimate and corporeal of human organs, the heart, to the far-away planetary bodies of the sky, connecting them through a series of meditations on the number 432. His search to mesh things together like this is not concerned with escaping reality, but discerning its underlying pattern and unearthing commonalities which thread dissonant things together. In this, he echoes Previn’s message about how essential it is to reach into our everyday lives, and not beyond them for a sense of the sacred. His work asks where we ought to look for meaning in our lives and suggests that the world of the imagination and the world of reality are not mutually exclusive.

…To suggest that the writer, the painter, the musician, is the one out of touch with the real world is a doubtful proposition. It is the artist who must apprehend things fully, in their own right, communicating them not as symbols but as living realities with the power to move… 8

|

| Ursula Major, constellation. Image held here |

The living realities in Dawson’s paintings are complex. In Big Bear there is again a marriage between heaven and earth. In the star-stained heights, the constellation Ursula Major can clearly be seen. An observatory to the left of the image, near the sunset, denotes mankind’s obsession with looking to the stars for answers. Echoing the constellation, down where the iguanas play, a real bear roots among litter as night approaches. The litter is a sombre reminder of what we neglect on earth and is one of the subtle references to ecology which permeate this exhibition. Linking the dissolution of art and the environment, Ewa Kuryluk points out in A plea for irresponsibility that “ the destruction of nature and culture [is] likely to annihilate [us] all ." She also writes,

…artists must fight for autonomy: their right to explore and express whatever they find important or interesting…Another reason why I plead for an irresponsibly private pursuit of art is my wish to see it survive… 9

|

| Verne Dawson , Big Bear, 2002, oil on canvas, collection of Chris Ofili, photo credit: the author, image courtesy the Douglas Hyde Gallery |

The word irresponsible is used in a nonpejorative context here. Irresponsibility does not mean a lack of concern for political issues; instead, it represents individual freedom, and Kuryluk’s essay promotes the idea that artists should be liberated from any obligation to convey a socially responsible message in their work. She argues that artists ought instead to be left to follow private and personal passions with which they are genuinely concerned, and explore these on their own terms. Kuryluk points out that were artists to do this, then should their art communicate a political message, it would originate from a place of integrity and personal interest, and not from a place of obligation. Work born solely of the desire to convey a politically correct message is, according to Kuryluk, merely propoganda. She argues for the validation of expressing what is real for the artist, and that politics should thus be approached from a personal angle, if at all. In this way, she draws her ideas out of the same feminist school of thought which inspred Dory Previn’s song; an ideology that unites different aspects of life such as the personal and the political; the spirit and the body. Dawson, like Kuryluk, emphasises the importance of freedom for the artist, but he also indicates a clear sense of the artist’s role, or social responsibility;

I think students are taught that they must narrow down and have a signature style and a market for their work. I’m very skeptical of that, I think it shuts down the imagination and it denies the richness of the experiences that we have. I just wanted to be free. Freedom is of enormous importance to an artist. We’re in the age of specialisation but I think the duty of art is to try to integrate all these things. 10

And in surveying Dawson’s work, it seems possible that personal vision and political message can also be reconciled: The litter in Big Bear does not moralise from the canvas; and the vision offered in Earthly Paradise is more imaginative and visionary than critical or judgmental. Dawson is clearly not afraid of following personal desires and yearnings in his work, not afraid to be somewhat irresponsible by Kuryluk’s definition. Not if freedom is the prize. The zodiac in Celestial Atlas, 2001 is indulgently filled with invented sea-creatures, as well as the established order of the stars. Perhaps this also represents a desire to unite what is down here with what is up there ? People walking with their feet on the ground, yet looking to the sky…

|

| Verne Dawson, The Discovery of Venus, 2001, 76 x 91 cm, collection of Chris Ofili, image courtesy the Douglas Hyde Gallery |

In The Discovery of Venus, Dawson has attempted to represent the moment when a prehistoric family first saw the planet Venus. He has reached through his imagination, into history, to find and represent an actual moment which must at some point have occurred. He has then given us a subjective translation.

The artist is a translator; one who has gathered from stones, from birds, from dreams, from the body, from the material world, from sex, from death, from love. A different language is a different reality; what is the language, the world, of stones? what is the language, the world, of birds? Of atoms? Of microbes? Of colours? Of air? 11

His search to represent prehistory in paintings such as The Discovery of Venus is a personally important quest which he generously offers to share with us. Yet there is an underlying politic, wanting us to be more aligned to our shared histories and our environment. Ideas of uniting opposites also find expression with Dawson’s regular use of circular canvases, which also pertain to cycles in life and time. Dawson’s series entitled Studies for Cycle of Quarter Day Observances. Spring, Summer, Autumn and Winter are depicted with related symbolism and imagery; in Spring, 2001, a woolly mammoth is ridden by a woman bearing a cornucopia. As in Sunrise, where the time of day is simultaneously used as an allegory for the beginning of the world, and an actual sunrise, the spring referred to here is both the spring of the year, and the spring of human existence; the early days of hunting and gathering. The woolly mammoth in Spring was faithfully copied from a cave-painting, because there existed no more accurate depiction of this animal’s appearance.

All painting is cave painting; painting on the low dark walls of you and me, intimations of grandeur… Naked I come into the world, but brush strokes cover me, language raises me, music rhythms me… if the arts did not exist, at every moment, someone would begin to create them, in song, out of dust and mud. 12

Paint also connects Dawson to prehistory; he says that it is his interest in history and the idea that people have always painted which drew him to the medium;

I think it might be… my feeling that I wanted to be part of a line of development of man – from the cave painters 35,000 years ago to the present, people paint. Essentially, we use the same tools – a stick with some hair on the end of it, minerals from the earth mixed with some oil. I love that sense that I’m doing the same thing that people have always done. 13

And so he paints; paints passionately, as best as he can, what he finds meaningful. He looks to the sky for inspiration, but the reason for this seems mostly to be that he seeks connection with the countless others who have done the same. Shared sky, shared earth, and shared history, are the sources from which he draws his original vision. His paintings reflect a sensual delight in the medium of paint and the naked bodies which play in the starlight in The Discovery of Venus are bound in a moment of wonder as celebratory and delighting as the colourful, vibrant paintings which inhabit this exhibition. Playing with iguanas and consulting the tarot simultaneously, it is a full apprehension of reality that Dawson seeks. A deep interpretation that includes the past, the future, the spirit, the sky, and the earth. His work is perhaps…

…a coded love letter and a private plea: to retrieve from the river of blood and time what’s irresponsible and mutual. 14

Felicity Ford is an artist and writer based at the moment in Killiney;she is currently involved with the installation of her sound-works in the end-of-year DLIADT graduation showcase, and is working with arts-and-theatre collective Spacecraft on their current production, Bleeding the System.

|

| Verne Dawson , Untitled, 2000, oil on canvas, image courtesy the Douglas Hyde Gallery |

Link: Interview with Verne Dawson, conducted by Eimear McKeith