Emma Haugh, Poverty of Vision, IMMA/NIVAL ROSC 50 1967 – 2017

Artist Research Commission, Irish Museum of Modern Art, 11 November 2017.

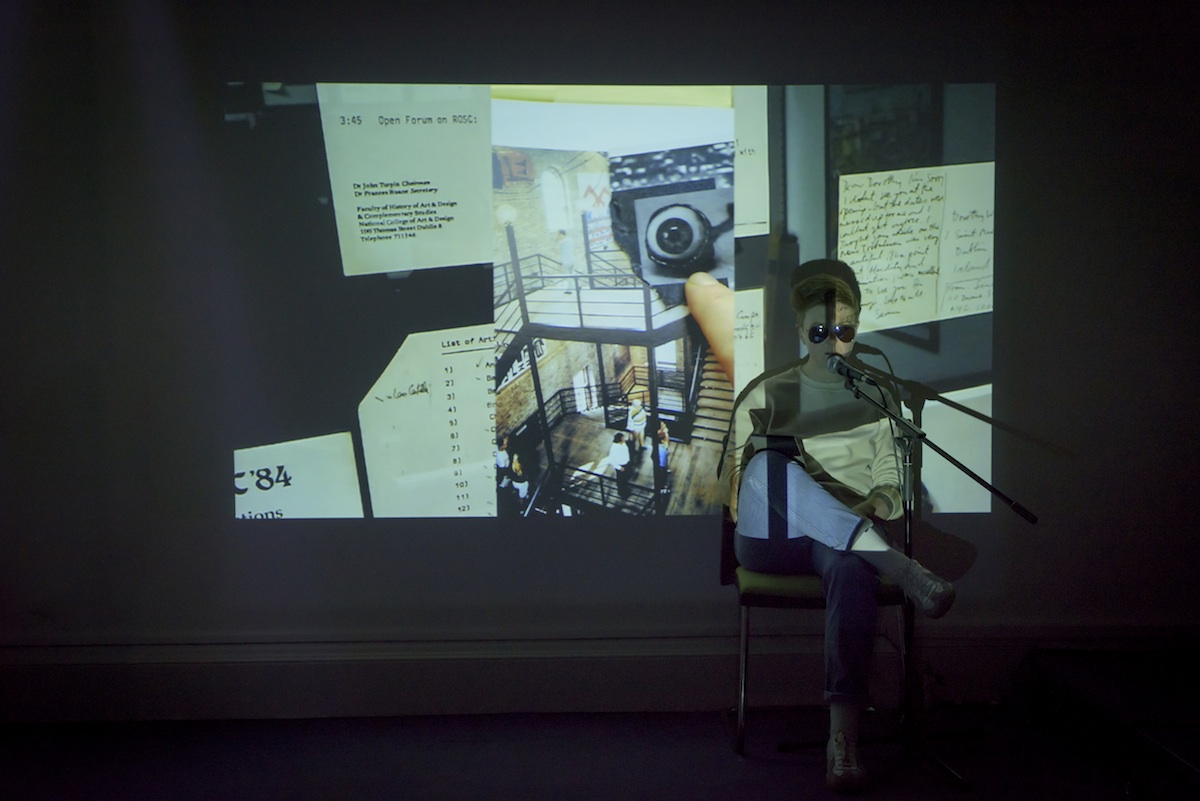

On the 11th of November 2017 the visual artist Emma Haugh presented her performance Poverty of Vision at the Irish Museum of Modern Art. It was commissioned as part of a year-long project between IMMA and The National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL) to mark the 50th anniversary of ROSC [1], – which was a series of “landmark visual art exhibitions in Ireland” occurring at roughly four year intervals between 1967 and 1988. The ROSC 50 project generally intended to explore ROSC’s “legacy and meaning in the present day” while generating “new research and new perspectives from both artists and audiences”.[2] Haugh spoke accompanied by a video projection of images, text and clips, with various prerecorded spoken audio, music and a take-home A3 print.

She paid particular attention to the ROSC of 1984, which was the year before the Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta fell, or was pushed, to her death out a 34th floor apartment window in Manhattan.[3] Ana Mendieta and her “aesthetics of disappearance” were not a part of ROSC, neither were a lot of other women. Haugh felt that which was not a part of ROSC, or its archival materials held by NIVAL, to be central in her pursuit of “speaking back to and with the archive in order to appear that which is not immediately present”, asking “how it is possible to intervene into and undermine the archives of power”.[4] She did so in this case by making an artwork commissioned to mark ROSC focused on what was absent from ROSC, looking instead to highlight people who were culturally, socially, institutionally and in many other ways, left out of, or excluded from, this experience.

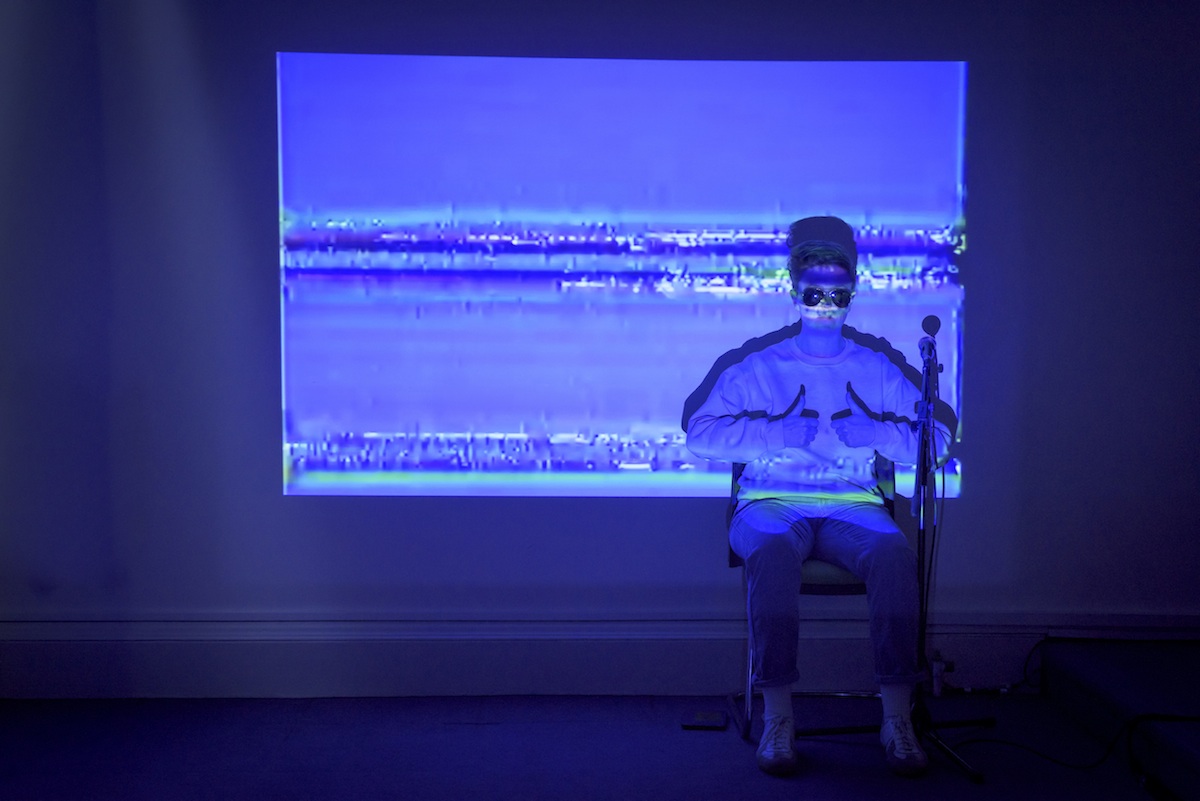

Throughout the performance Haugh was sitting directly in front of, and therefore inside, a video projection, and speaking into a microphone on a stand. Sometimes she’d stop talking and push the swinging mic off to the side in a cool way and let a prerecorded section of distorted spoken audio or music play, e.g. Don’t You (Forget About Me) (Simple Minds, 1985). We saw and heard excerpts from and about Footloose (1984), The Breakfast Club (1985), Richard Serra, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, people being crushed by sculptures/sculptors and, of course, Ana Mendieta, amongst others. Haugh spoke with a clear, calming voice and the material’s delivery was not unlike that of a trusted general practitioner, your mom’s old teacher friend or maybe Irish Siri in ‘poetic’ or ‘introspective’ setting – her voice seemed to know a lot and you believed what she said.

We heard of experiencing ROSC 1984 as a young girl, another girl was there too. There was urination and minimalism and these people, these girls, experiencing this stuff and this place and each other and their experience mattering. You felt what the voice felt and it felt like loss. Greater than loss, as it seemed to tell of an experience it never got to have in the first place – articulating a void. This account was a retelling, an act of reclamation; both bitter for a past that wasn’t permitted and sweet for a retrospective formulation of an alternate space of possibility.

It was the first time I have ever wanted to cry, for the right reasons, due to performance art. Haugh was wearing sunglasses and a good thing too, as had I looked in her eyes it might have had a Medusa reversal effect, enlivening me too much – better to be set in stone. It’s not appropriate to feel EVERYTHING at three in the afternoon on a weekend at a sober seminar about a visual arts biennale that stopped happening thirty years ago. It would have been inappropriate to weep.

But what are the things we’re allowed to feel strongly about at 3pm? Or, rather, at any time? When I do feel strongly about something and express this fervour, I’m often told, and often, always and only, in fact, by men, that I am taking something ‘too seriously’. I would perhaps venture my interlocutor to be not taking the serious thing seriously enough. But the real problem, the unspoken, underlying issue, is really that they do not take me seriously and therefore can not take me or the thing, whatever it may be – any or all of the things that the world is and contains, seriously when it is me being serious about the serious thing. The thing is no longer serious as I taint it by my nature. I am not taken seriously because I am a woman and by extension nor are my experiences. Neither, seemingly, was the work, or perhaps even the death, of Ana Mendieta, and countless other women. Alternately, men are, by their nature it seems, unquestionably serious beings and in so being can deem whatever they like as serious as an extension of their serious nature. Men can bestow things with their inherent power. Robert Morris’ L’s or Michelangelo’s Adam. Thus are the transformative superpowers of man.

Who possess superpowers but gods? This omnipotent power of man can be so difficult to appraise, scale or contain that it can permeate everything, be everywhere: man is god, god is man and, by the way both can be equally difficult to communicate with. Discovering and proclaiming the singular man to not be God can be a brutal, stony, lonely journey, plunging one far from the heights of heaven. Gods don’t like to be brought down to earth, but women quite easily can.

These heavyweight godmen and their collective knowledge and histories, their stories and images, their paintings and sculptures, weigh us down, push us from great heights down to the ground. Poverty of Vision was the pins and needles of awakening, an account of and incitement to experience: If we weren’t accounted for, let’s write new accounts. The benevolent, empathic, relational Haugh offered us all her capacities to think and feel oneself as a viewer [5] – allowing us room to experience and space for our experience to matter. Haugh then utilised the experience as material in sculpting an alternate reality, where we could all be serious about the serious things, and be the serious things ourselves whilst openly weeping and leaping with abandon, bounding skyward on our reanimated limbs. That is some sculptor. That is god-like.