The life of Irish artist Alanna O’Kelly can’t be understood without an artwork which also points towards a kind of art history in Ireland. It comes, perhaps unsurprisingly, from an experience outside of the island as an immigrant in the UK. In a 1994 interview, she reflected on how conversations with English people would get stuck, whether it was about the political tensions in Northern Ireland or the legacy of the Great Famine. “I’m an educated Irish person, I’ve been through third level education, I [had thought I] have it sussed,”… she said, adding she had turned a “wilful ignorance” on Irish history. [1] The piece, Sanctuary/Wastelands (1994), articulated the deep cultural scars of the Famine, the huge void of this enormously dark time, as she described it, had rarely been addressed in Irish art until then.

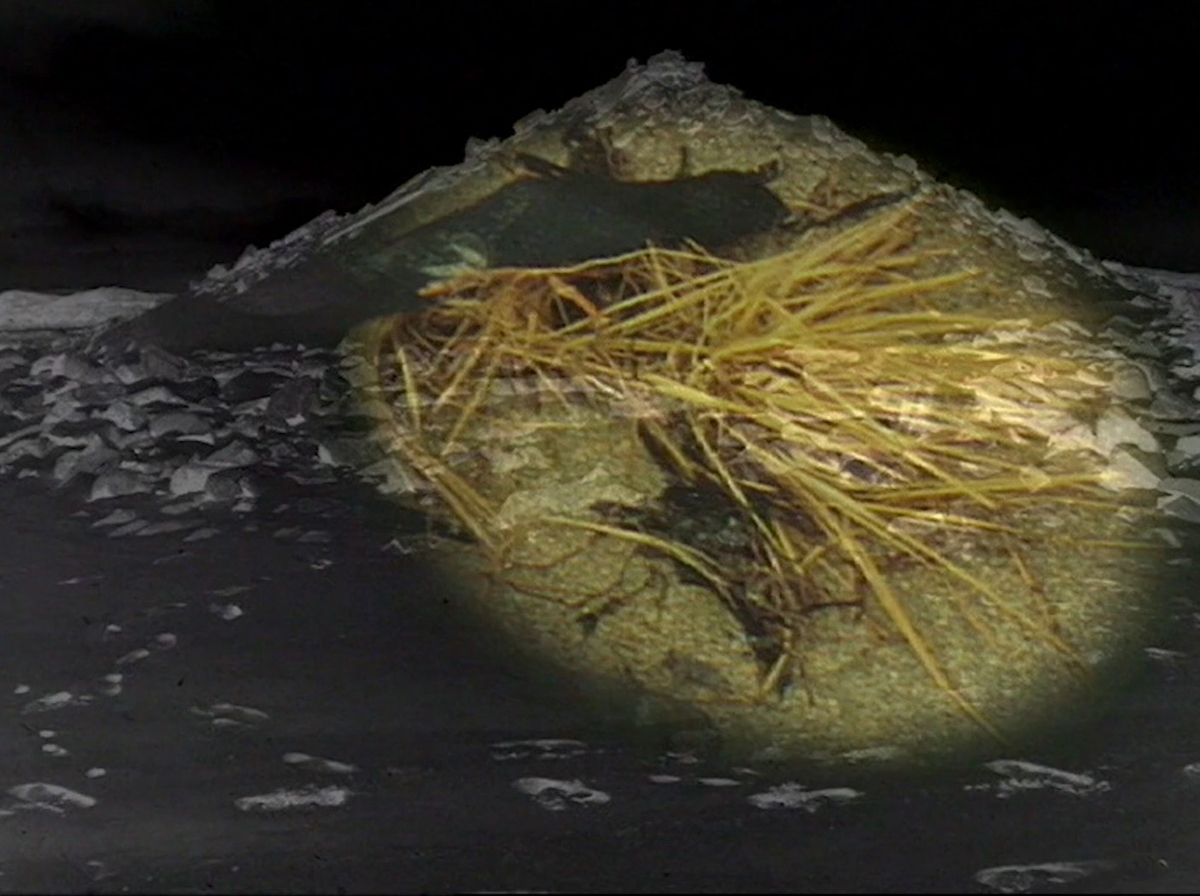

I am writing from London today, and I was two years old when this piece was made. I moved here, as many have before, in the midst of a struggling economy, looking for a job as much as a sense of change, excitement and opportunity that felt impossible ‘back home’. I left after the centenary of 1916 and as the UK was voting for Brexit. Irish identity was never so visible: one part Fáilte Ireland tourist-targeted marketing drive, another part simmering tension along the border.

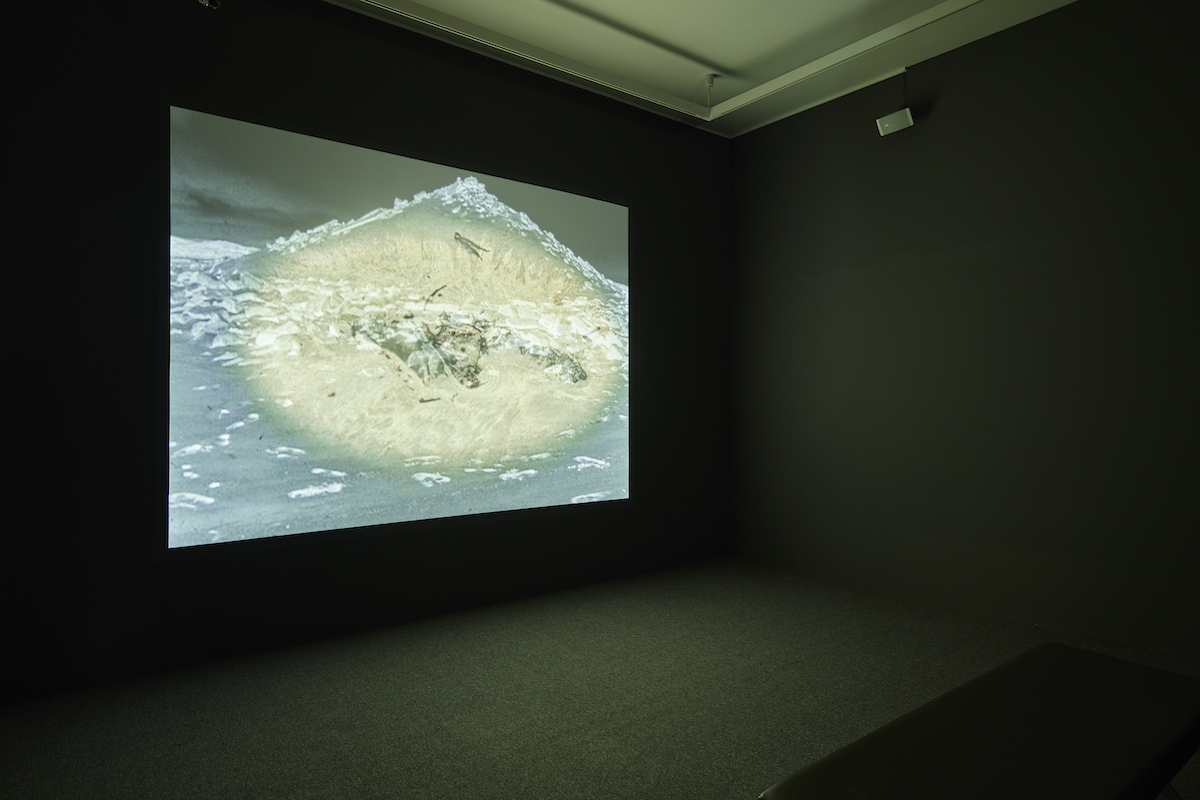

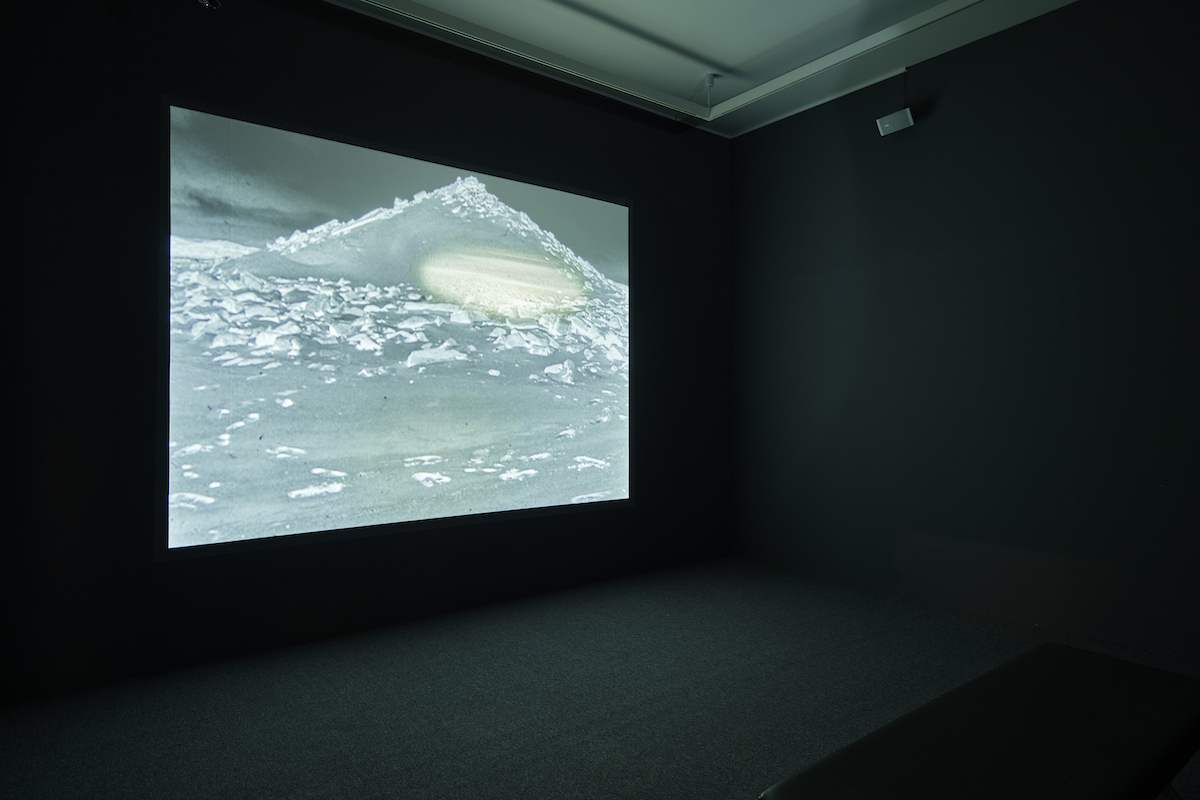

Sanctuary/Wastelands is being presented digitally as part of IMMA’s response to Covid-19. The lockdown cut short the museum’s exhibition IMMA Archive: 1990s From The Edge To The Centre that featured this work, alongside a broader presentation of their digitisation of the archive ahead of the institution’s 30th anniversary.[2] Such notable moments and historical accident surround O’Kelly’s life and work. [The IRA bombing campaign in the 1980s made life tough for Irish people in the UK, which would have heightened the context for her exploration of Irish identity while as a student at the Slade School of Fine Art.]

O’Kelly made the piece a few years before the Great Famine’s anniversary, whose aim, Catherine Marshall commented [3], “was to attract more commercially minded and conventional responses” from Ireland and abroad which “spawned a flood of sentimental projects all over the country, commemorating famine and victimhood, ironically during the first flush of Celtic Tiger prosperity.” [4] The American investment bank Morgan Stanley would coin the term Celtic Tiger the same year Sanctuary/Wastelands was created.

The Famine was the furthest thing from my mind before going, as was any felt sense of Irish identity. It’s when you’re away – anywhere, as long as it’s not home – that you feel different and that difference becomes noticeable, something to figure out. It’s thrilling – in a realising your grandmother met the Sex Pistols kind of way – to reimagine Irish identity as being not only about high rents and low corporate taxes, Americans on holiday for trad music and the Guinness factory, but about the tragic consequences of Empire and sites of mourning, loss and even resistance.

As O’Kelly’s ode to Ireland’s great trauma is presented again today, we’re facing another iconic moment in Irish history. I spent my life hearing Ireland’s two main political parties – born out of the Republic’s formation and following civil war – that led every single government would never work directly together. Plot twist: that’s exactly what’s happening now. Ireland today, the Ireland they have created together, does not describe itself as a postcolonial state. The best small country in the world to do business, said a previous leader.

Looking at rents, housing and job opportunities, it’s hard to get excited about what’s on offer. The grand realignment of the two giants of Irish politics feels more like a closing off of possibilities, than any kind of new beginning. The centre will hold, it seems. It is because of the Covid-19 restrictions that Sanctuary/Wastelands is now readily available to the many who have left. Ireland’s diaspora don’t often factor as an audience despite so much of our culture being born in and shaped by this experience. Many find their roots from leaving and are then left behind. It seems fitting, if only as an awkward outcoming of happenstance, that this work finds a second life digitally – accessible for those figuring all this out as they find a home elsewhere, just as O’Kelly did.