|

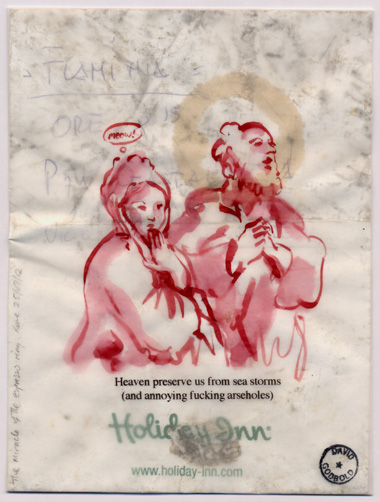

| David Godbold; Meow! (The miracle of the espresso ring), 2002, Ink & computer printout on tracing paper over found paper with espresso ring, 14.2 x 11 cm: courtesy Kerlin Gallery |

In the essay by David Carrier accompanying this exhibition Godbold makes a simple statement of his practice: ‘I am interested in the conflation of grand themes and daily minutiae’. Conflation is not simply addition, however: where the two come up against each other, both are shaken.

Godbold collects all manner of notes, lists, leaflets and bureaucratic statements, hoping to bring these discarded signs of everyday life back from redundancy. Most are written by an anonymous hand, or typed; some are invented by the artist himself. These signs are then overlaid with sheets of tracing paper, upon which Godbold has drawn, in an irreverent yet faithful style, religious imagery from his pet ‘grand theme’ – the Counter-Reformation. Whatever meanings leak from this conjunction are drawn out further by the addition of typed captions (also both found and invented), speech bubbles and marginalia. Reading through these, one is drawn in, then thrown off course by an unexpected aside. However stretched, these meanings remain in an unstable constellation about one another: but there are gaps, and these allow Godbold to insert political commentary, operating more often obliquely, by irony and insinuation, rather than by direct statement.

|

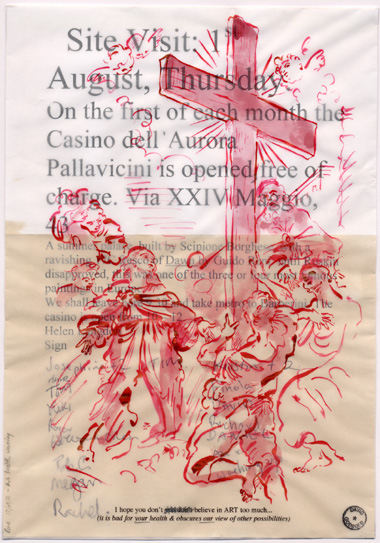

| David Godbold; I Hope You Don’t Believe in Art Too Much, 2002, Ink & computer printout on tracing paper over retrieved notice, 26.5 x 18.5 cm: courtesy Kerlin Gallery (text reads: I hope you don’t believe in ART too much… (it is bad for your health and obscures our view of other possibilities)) |

The Nietzschean world pieced together is nothing but a conglomeration of sensuous surfaces, malleable and improvised. Upon these surfaces image and text rarely collaborate: instead, there is a contest between the ‘higher’ truths of culture – transcendence, spirituality and morality – and the ‘lowly’ motives and hungers of the body these truths serve, whose aim is to propagate (precisely by disavowing its self-interest and showing itself to be sacred, refined, ‘cultured’, etc.) a hierarchical structure in which its self-image might dominate. Yet, for Nietzsche, it was the illusion of culture which also showed the ‘truth’ that there is no truth ‘behind’ this surface: that truths have never been more than provisional structures of difference within which particular bodies (of thought) can exercise their will, whilst justifying their domination of others by a self-imposed prerogative over what is most essential, or true. So, we might modify Godbold’s exhibition title and say; once it was the Truth, now it’s all lies, which is the truth.

|

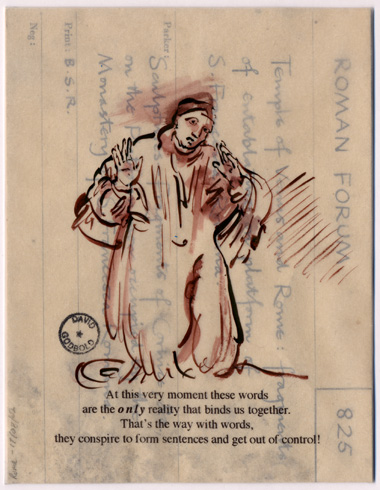

| David Godbold; The ONLY reality, 2002, Ink & computer printout on tracing paper over found paper, 13.6 x 10.6 cm: courtesy Kerlin Gallery |

Restricted to the play of this surface, Godbold can only use the terms of culture to criticise culture itself. Yet, can one use a flawed means to criticise those means? Only at the risk of sawing away the branch one is sitting on. And in a world where the only interpretation possible is that there is no interpretation, the artist as a satirical appropriator of signs becomes itself a quasi-transcendental principle. How, then, is political commentary to avoid being just another fiction to pit against others?

And, is there not a point at which scepticism begins to confirm the object of its suspicions? Does it not implicitly demand an answer that would give it the faith that it feels it lacks?

Furthermore, Godbold remains ambivalent towards his cultural sources. Although he shrinks his source imagery, refusing its previous grandeur, and any thematic unity is constantly checked or undercut by other images down the line, still, this is not a straightforward refusal. Broadly speaking, the visual codes of the Renaissance which the Baroque inherited were used with wit, irony and metaphor, as only a mother tongue can be. Similarly, at that time appearances took precedence over essences as the movement and exuberance of multiple sensuous surfaces overran underlying structures. Godbold seems to confirm that approach to the world propagated by his adopted mother tongue precisely in turning its codes upon themselves.

Thankfully, Godbold does not attempt to iron out these contradictions. Instead, he overloads his visual imagery, putting it under strain, so that there might appear at least some negative image of a different concept of measure – one that does not hide its material conflicts behind some anodyne ideal or spiritual unity. It is, then, by restoring the contradictions of a forgotten sensuality and its fragmented identifications that Godbold, almost despite himself, makes his boldest political statement.

|

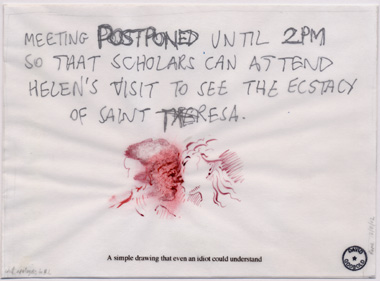

| David Godbold; A Simple Drawing, 2002, Ink & computer printout on tracing paper over retrieved notice, 13.2 x 18 cm: courtesy Kerlin Gallery (text reads: A simple drawing that even an idiot could understand) |

The phantasmagoria of the Counter-Reformation sought to mediate and redirect the possibly disruptive agency of its audience by making Catholic ideology tangible, through a direct appeal to the senses and emotions. By techniques of suspense and wonder it seduced rather than coerced its audience so that they might once again recognise themselves in the preconfigured narrative of Catholicism. Central to this seduction was the ecstatic appearance of the sacred in everyday experience. But, at the same time, this appearance had to continuously evacuate the real from itself, in the form of the more base appetites of the body that it worked upon; otherwise its divinity would deflate.

|

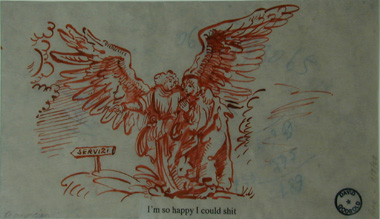

| David Godbold; The conversion (servisi), 2002, Ink & computer printout on tracing paper over found paper, 10 x 17.5 cm: courtesy Kerlin Gallery (text reads: I’m so happy I could shit) |

Countering this, Godbold shows Catholic heroes, saints and adventurers at the mercy of libidinal urges, self-serving and masochistic, and often simply drunk. Like all good satirists, Godbold disarms one with humour, knowing that jokes, like art, play on doubts, bringing the unexpected together and confusing codes: and a joke, similar to Godbold’s image-texts, is more an act than an argument – thus, its directness. And, of course, there is nothing quite like a joke to do violence to what is held most sacred, suggesting that, in ‘true’ Nietzschean fashion, we should forego all ideological consolations (including, of course, elements of Godbold’s works themselves), and let ourselves dance, laugh, fuck and shit on the edge of the abyss.

This might be the principal axiom of consumer hedonism. The libidinal appeal of the Baroque phantasmagoria is seconded in the spectacular imagery of consumer society. And by operating upon a body which is allegedly impervious to ‘ideological consolations’, both make their ideologies ‘second nature’.

|

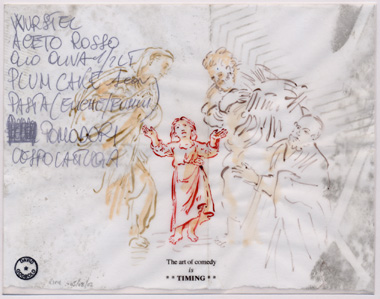

| David Godbold; The art of comedy is TIMING, 2002, Ink and computer printout on tracing paper over found shopping list, 15 x 19 cm: courtesy Kerlin Gallery (text reads: The art of comedy is ** TIMING **) |

But an attitude of laissez-faire remains hedged in by certain habits appropriate to the ideology in question. Perhaps a fulsome belly laugh in the right place would be conducive to shaking off these habits. Indeed, a recurrent caption in this exhibition tells us, ‘the art of comedy is timing’, and without doubt, Godbold’s delivery can rarely be faulted. However, his aim is occasionally scattered, and he ends up pissing into the wind.

Tim Stott is an art critic based in Dublin.