Laurence Counihan: Aoife Claffey

Armen Avanessian and Suhail Malik have proposed that we now inhabit an era of the post-contemporary. The acceleration of planetary-wide network computing and information technologies eviscerate any traditional shared conceptualisation of time, which has resulted in a crisis of speculative temporality where “time arrives from the future.” Rather than the longstanding organisation of time discretely periodised into durations of years and months, our contemporary moment is now perceived as increasingly short fragments that causes the future to collapse into the present.[1] This tendency is compounded by the fact that now whenever visions of the future do give themselves up to us, they appear overrun by spectres of collapse that are political, economic, or perhaps most clearly, ecological. Such epistemological instability about the future – which appears as either impossibly immaterial or materially catastrophic – naturally manifests as a desire to retreat into the past, but more importantly, one that is solid and concrete, graspable and knowable. In such a climate the allure and aesthetic value of ruins appears strong, as not only do decayed monuments exist as signifiers that herald the natural passage of time, they also allow the human subject to reorient themselves in relation to more stable and traditional temporal categories.

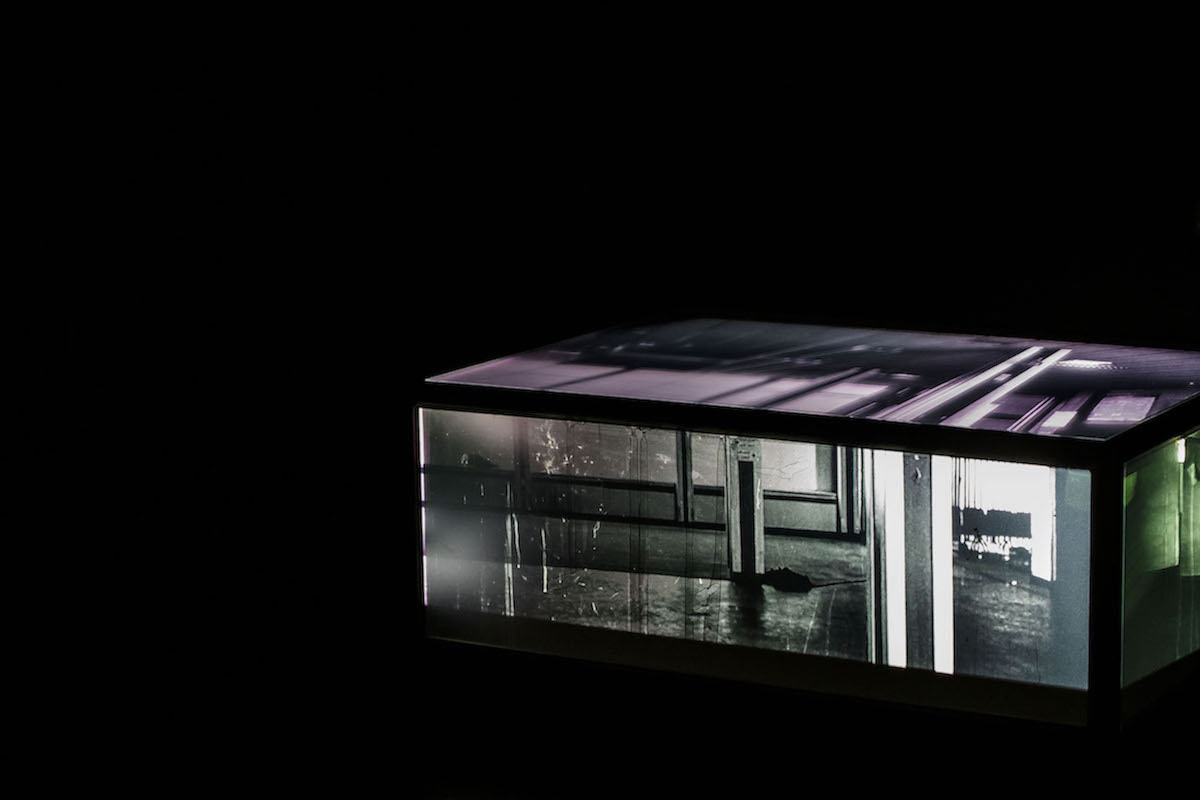

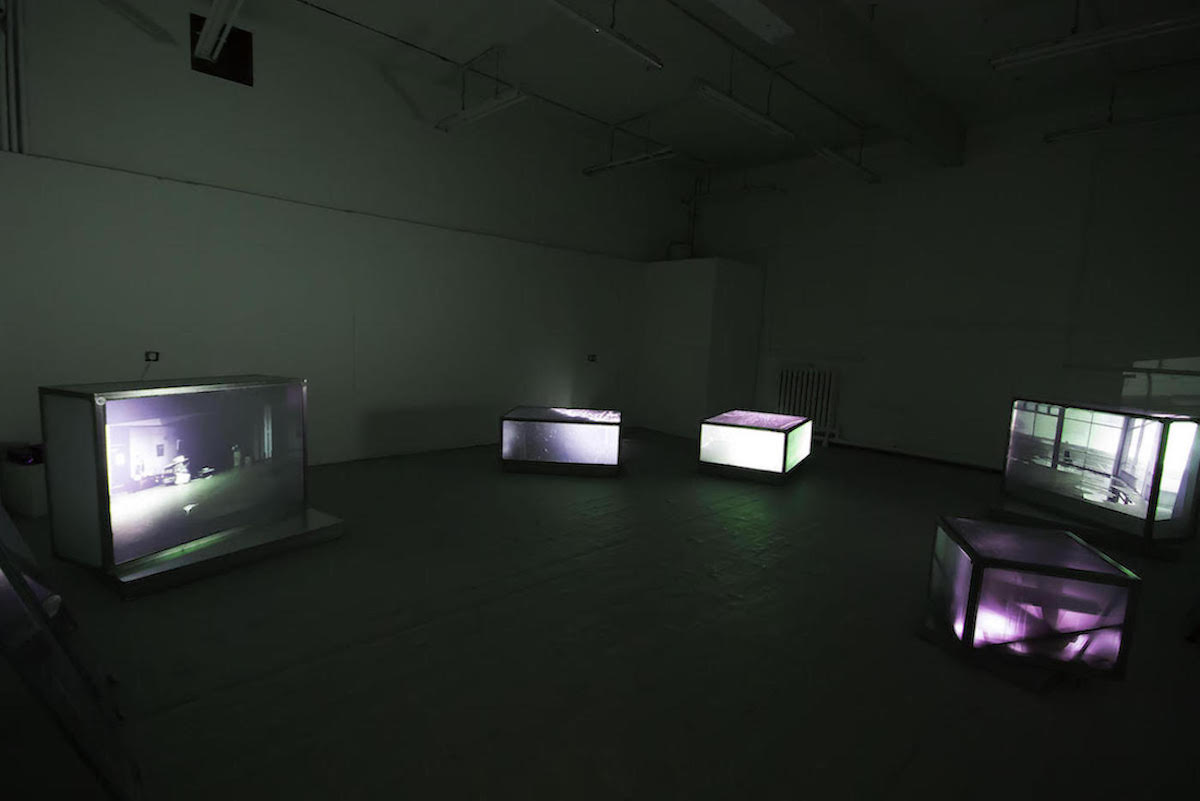

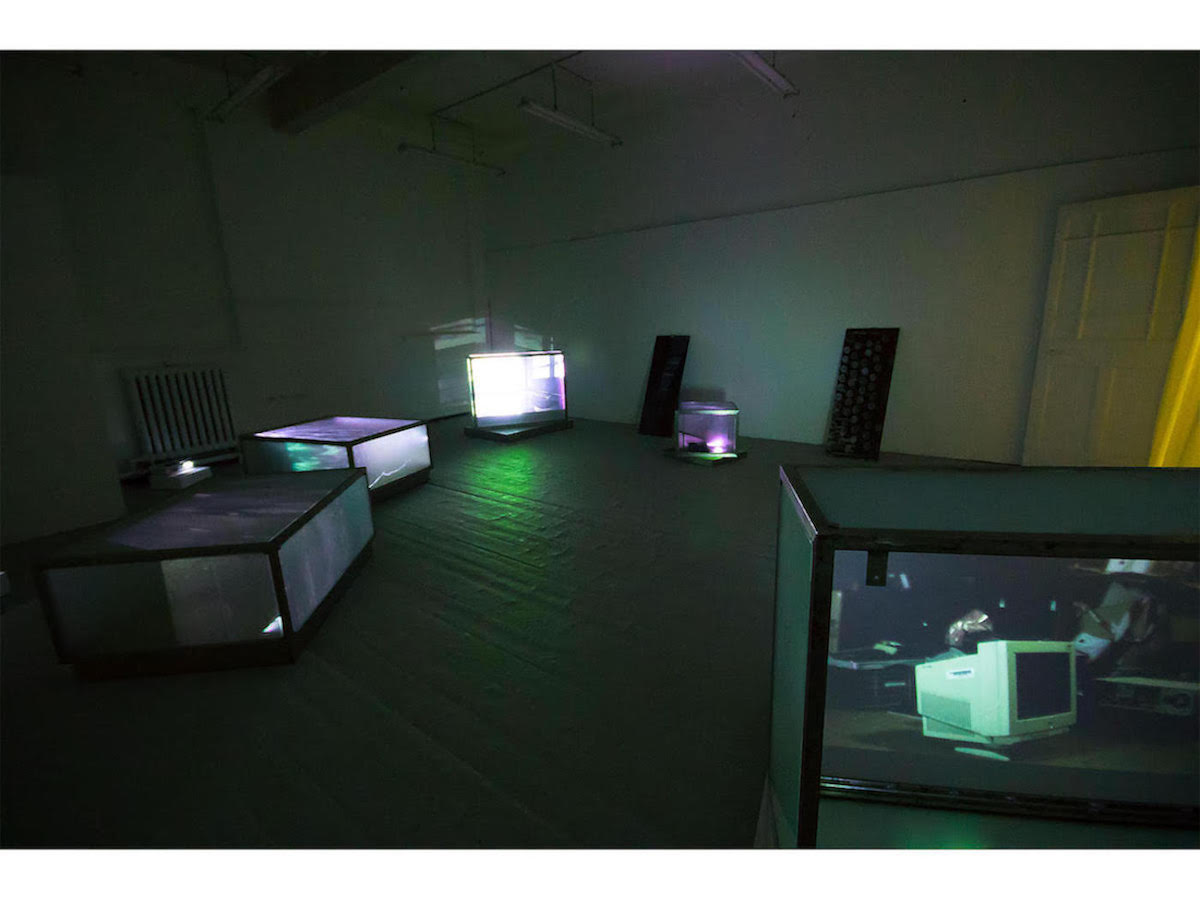

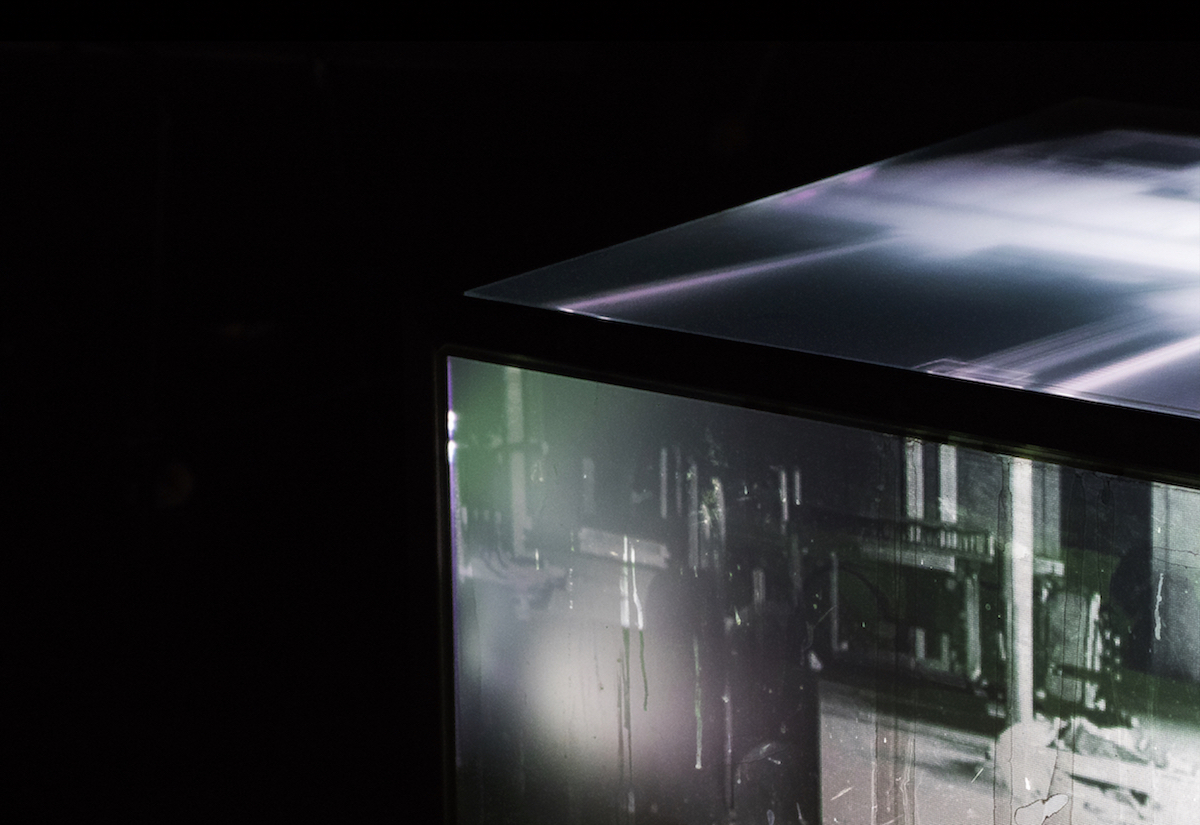

This exhibition value of blasted ruination forms the basis of Aoife Claffey’s work at this year’s Dismantle exhibition, the 2019 iteration of the Crawford College of Art and Design graduate show. Combining photography, video, sound and found sculpture, the source material is the old terminal at Cork Airport (which ceased operations in 2006). The subject matter is hauntingly reanimated in order to partially summon the beguiling allure of ruinous architecture from our recent past. In the darkened installation space – engulfed in ominous drones that bring to mind the sound of jet engines – five lightboxes, arranged at the periphery, serve as the focal points of the work. The two most dominants display looping video material, as we are led around the dilapidated terminal by the disembodied mechanical eye of the camera. Every shot pans slowly across the decaying enclosure as we are greeted to scene after scene of the building in a state of collapse: peeling paint and missing roof-tiles, stacks of cardboard boxes, partially flooded flooring, an arrangement of old and ravaged computer equipment, and a reoccurring visual motif of abandoned seating.

Chairs – some arranged row after row in empty waiting areas, others loaded on top of one another, and others still presented arrestingly in the singular – appear as the clearest evaporated trace of the human bodies that have been expunged from the setting. Herein, Claffey’s work makes allusions towards the concept of non-place: spaces within supermodernity that anthropologist Marc Augé describes as transitory and not “defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity.” Supermarkets, airports, hospitals, video game arcades, train stations, Internet cafés, and nightclubs, are all examples of non-places. Although they are consistently populated, the inhabitants are always in flux. They can operate under either “luxurious or inhuman conditions”, but what is important is how they always exist for the subject as fleeting or temporary.[2] Within the artist’s installation, the transient character of the airport terminal as non-place is intensified, as emptied out of all activity it morphs into a kind of dead non-place. This doubling of negation (non + dead) is amplified further still by the seemingly inherent non–graspability of the source material.

Rather than the ultra fidelity of HD screens, the chosen method of display – wherein the video is projected inside the lightboxes – causes the footage to exhibit a muddied, oneiric quality. Everything in the environment feels de-sharpened, as if steadily lurching towards the edges of representation. Another lightbox depicts more abstract moving images; an overhead view of waves steadily crashing over a landscape, occasionally revealing rusted objects partially submerged in water. This tactic of obfuscation and partial revealment also emerges when attempting to view the photographic works within the space, as the low lighting stifles any attempts to clearly discern what adorns the image surfaces. On closer inspection a pair of digital prints resting against the wall confront the viewer with an array of steel girders that seem to menacingly conceal what lies within. Another photograph of circular tabulator keys initially causes confusion, as what is being looked at appears as abstract and strange, temporarily unidentifiable. The images feel as if they can never be clearly seen, their content remaining frustratingly out of grasp, as darkness veils them in a cloak of illegibility.

Returning to one of the videos exploring the abandoned terminal, it is now showcasing a close-up of a disused escalator, with the artist’s steady movement up the stalled mechanical steps mimicking the previously automated activity of the machinery. Then as the camera reaches the summit, a sudden blast of light rains down, momentarily illuminating the installation environment, and it seems as if for a brief second the photographs can perhaps be properly seen. However, just as quickly we are returned to darkness, and the images are once again obscured. This omnipresence of ungraspability that defines the installation appears, in the contemporary moment, as a gesture towards our rapidly changing relationship to the concept of linear time and traditional temporal categories. Airports appear self-evident as one of the prototypical exemplars of 20th century architecture, embodying not only the action of physical movement and travel, but also signifying a more generalised idea of progress into the future. Returning to the airport as a site of shared historical memory conjures the spectacle of a forgotten future, one wherein the idea of futurity itself appeared as somehow more concrete, stable and knowable. Yet in Claffey’s exploratory retreat into this architecture of the recent past, all representations appear as either ruinous or indefinable; the airport as a physical location that previously signalled towards a progressive future, now only returns images of murky decay.