Sarah Kelleher: Seán Rhatigan

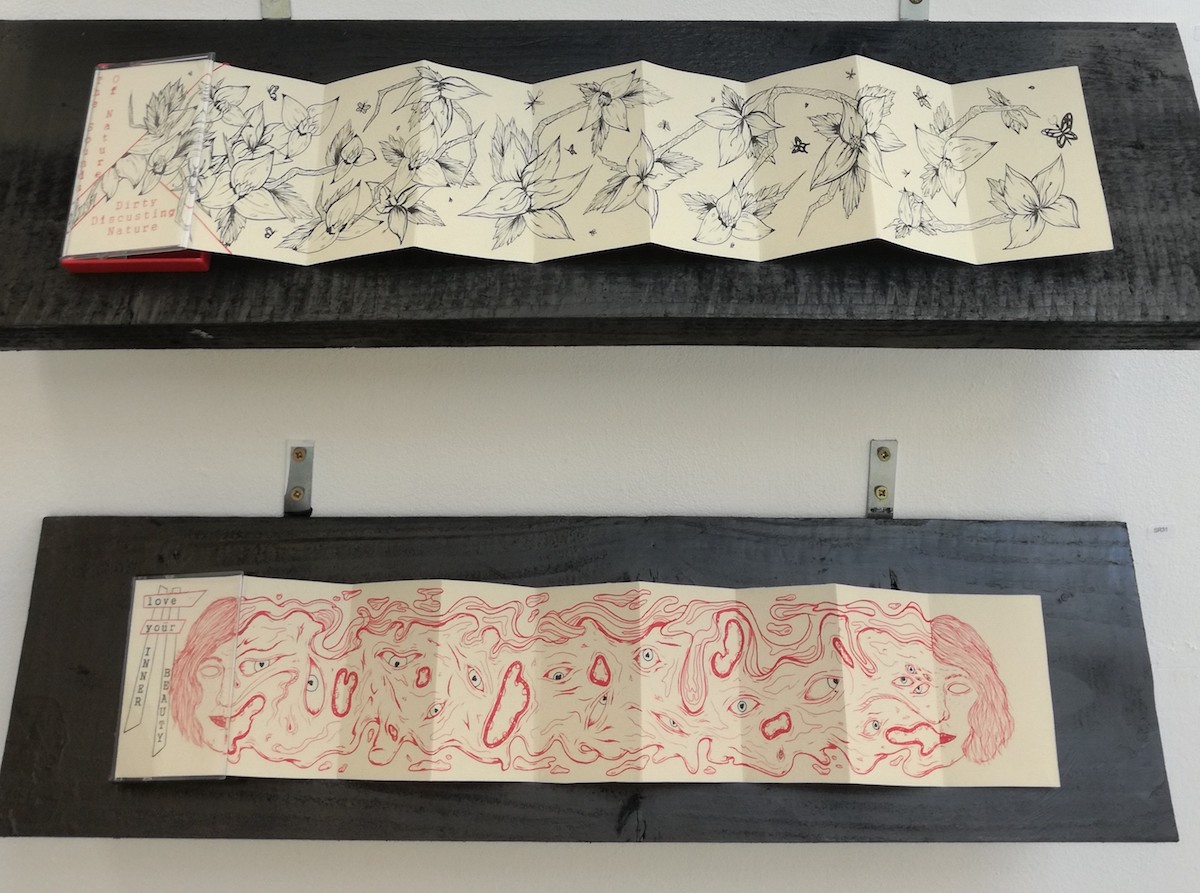

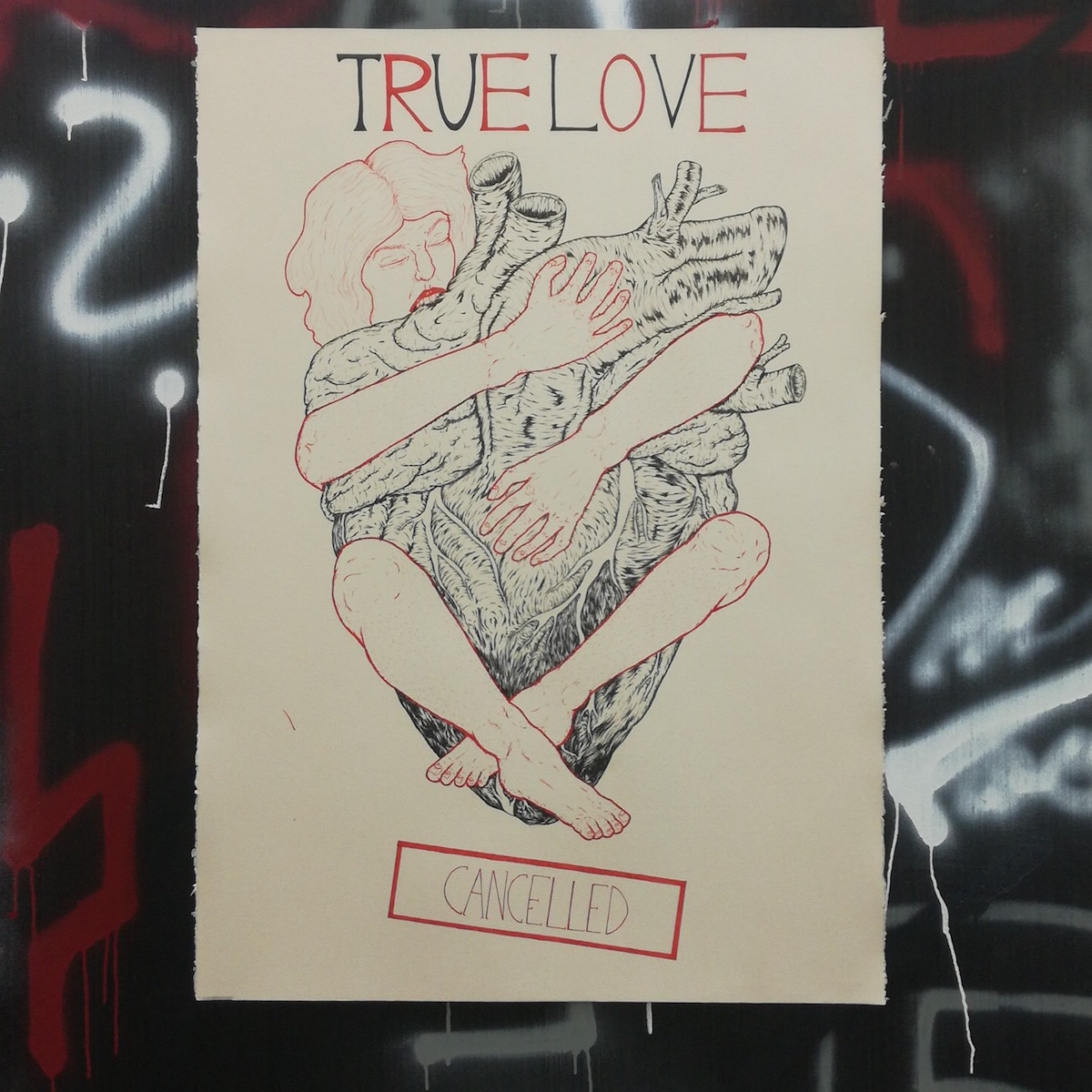

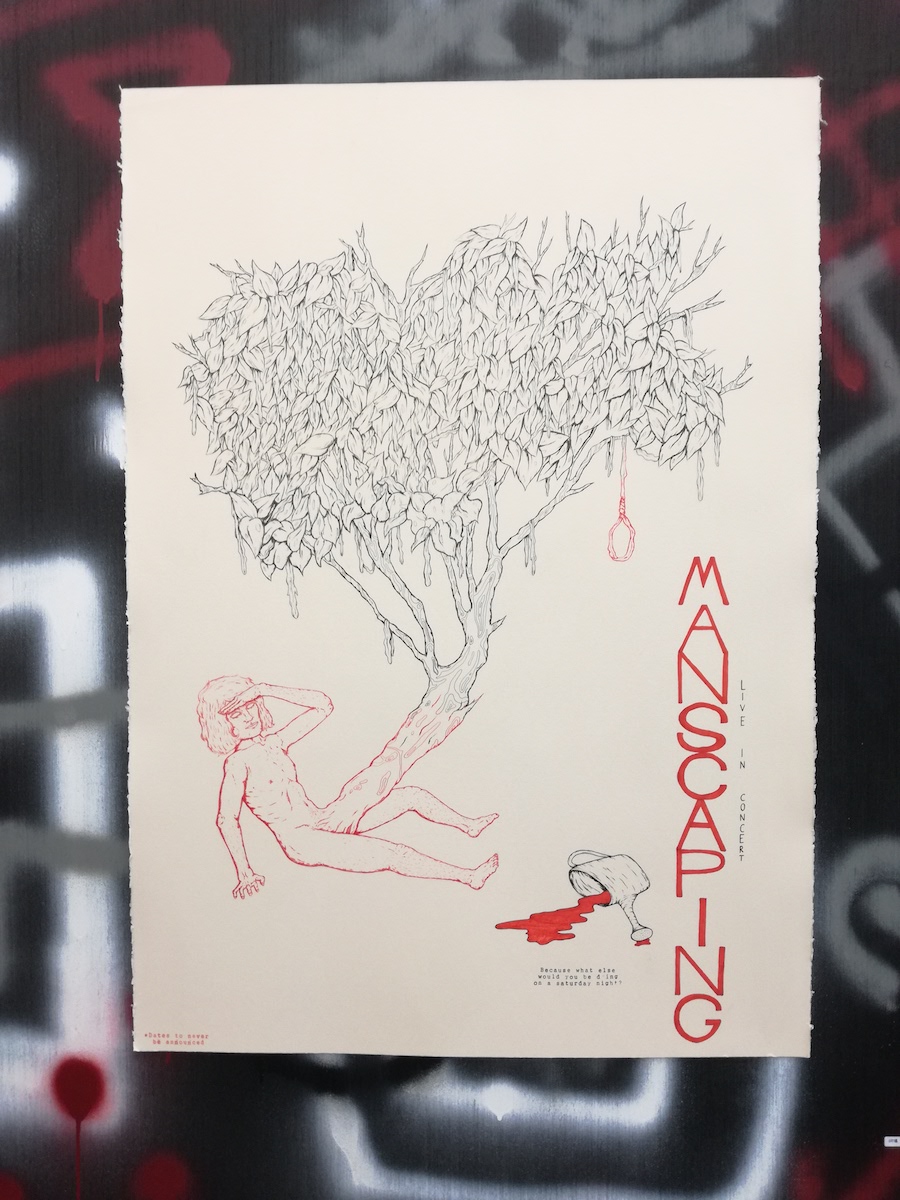

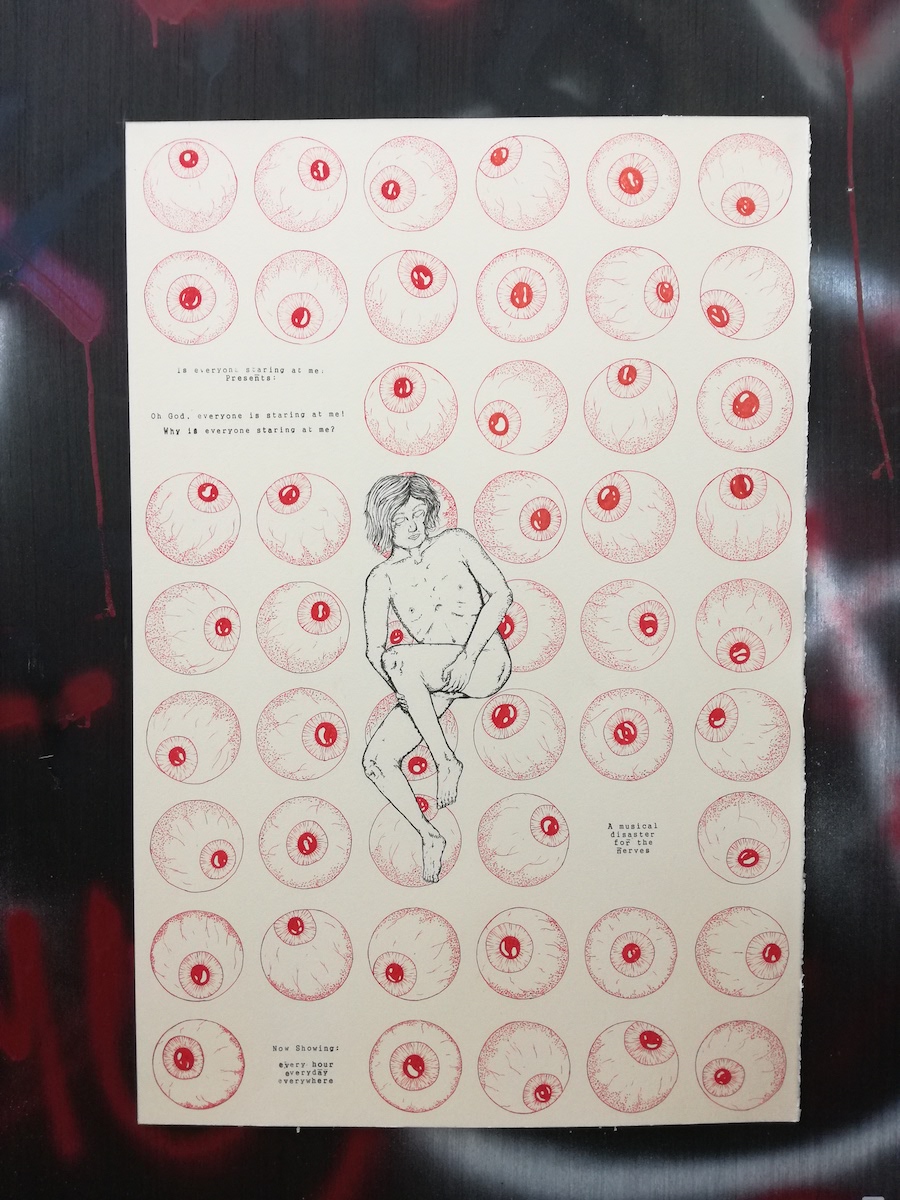

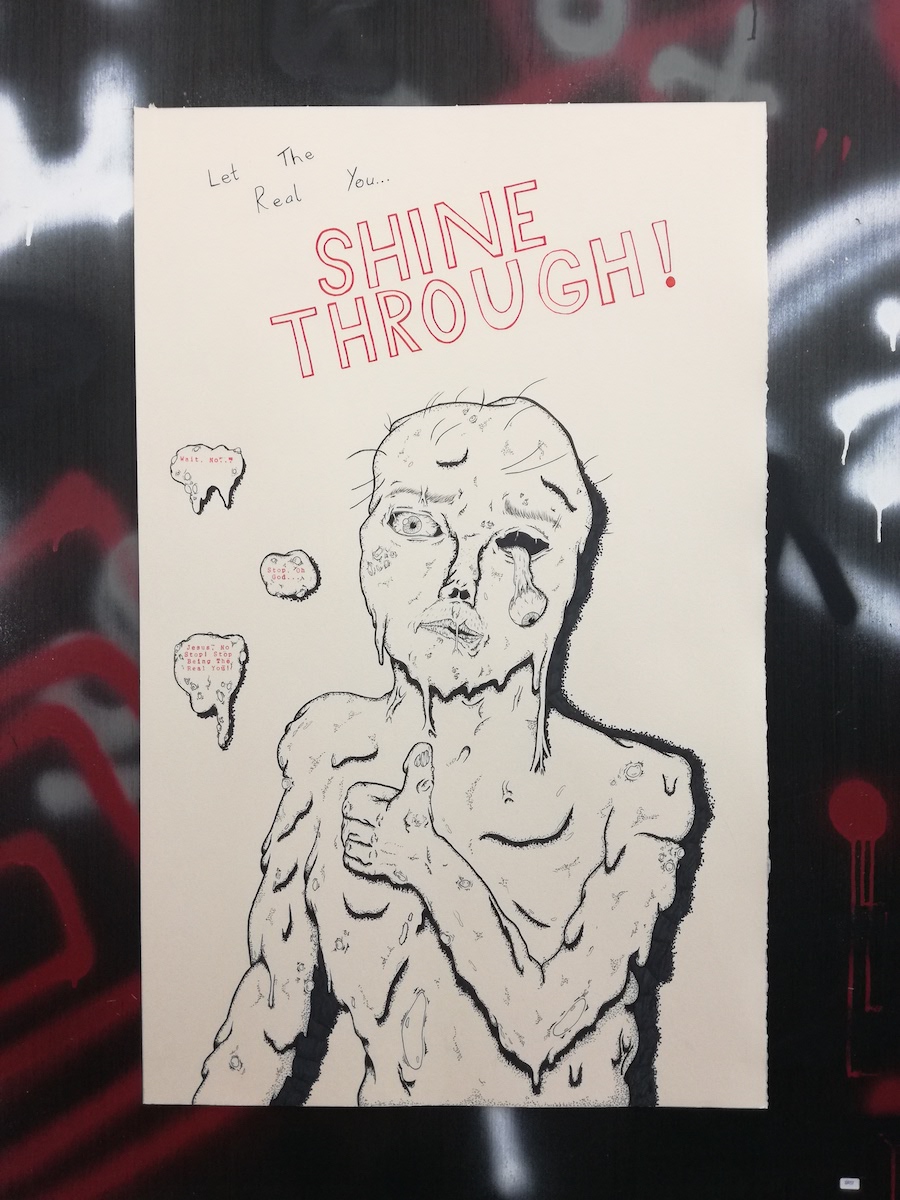

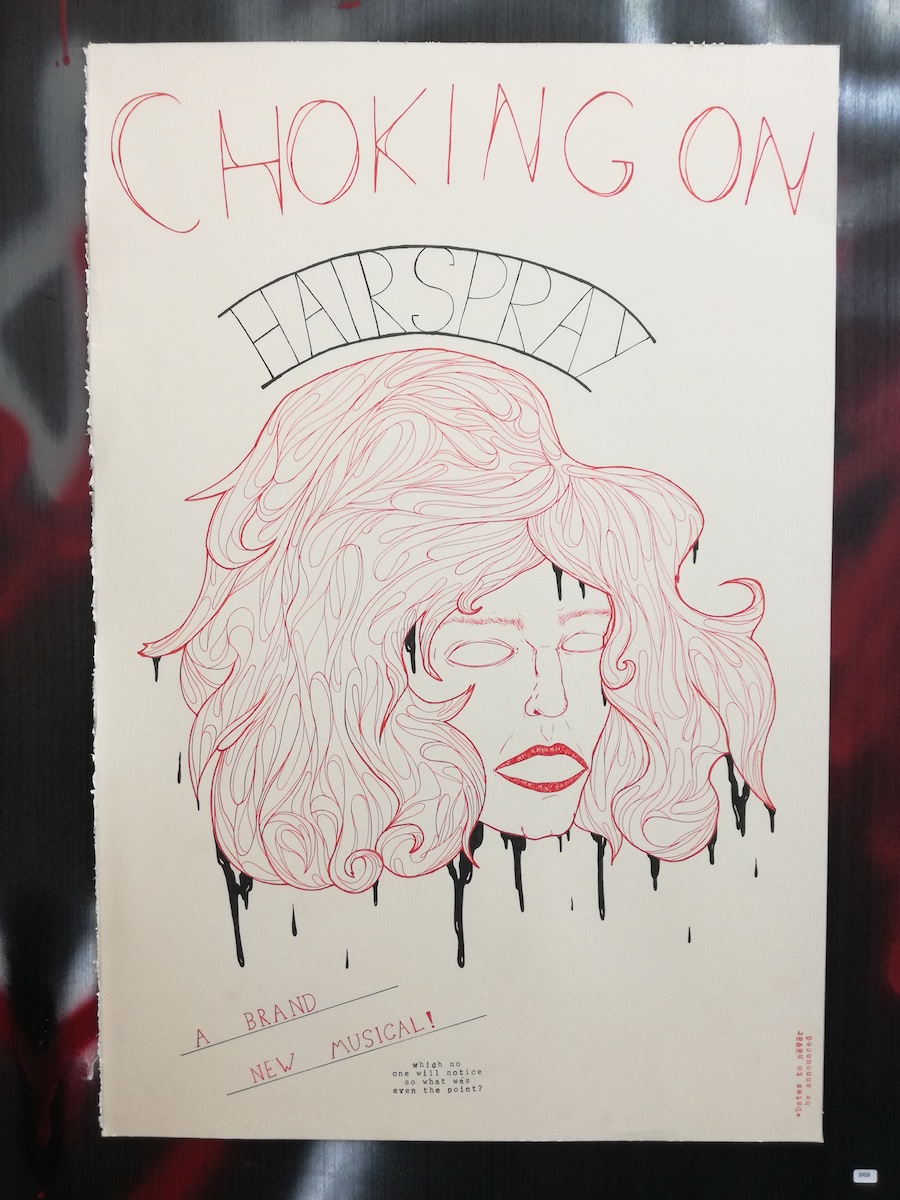

Drawing was resurgent at this year’s CIT CCAD degree show, as was a pronounced return to figuration. Amidst this, Seán Rhatigan’s work was notable for its distinct and fully realised aesthetic. His show explored sexuality through the lens of loneliness, self-consciousness and frustration in a presentation headily reminiscent of an alternative music venue cum adolescent bedroom. Against a roughly spray-painted background, Rhatigan showed poster-sized drawings in red and black pen on brown paper, with cassettes and cd covers balanced on narrow shelves. Drawing as a practice has historically been fetishized as the most intimate and revelatory form of artistic expression, functioning as a kind of Richter scale registering what Robert Morris acidly termed the “trembling [of] so many little exposed nerves […] beneath the neuritis and nostalgia of the cross-hatching”.[1] Although Rhatigan’s presentation was visceral in its evocation of the roiling, hormonal complication of lust, loneliness, disgust and shame, his use of drawing is more interesting and more critically informed than a simple register of emotional intensity. His considered lo-fi aesthetic is in dialogue with a history of practice, channelling Raymond Pettibon’s aggressively satirical combinations of figurative imagery and enigmatic texts – text is as important as image in Rhatigan’s work – as well as the underground music scene of the 1990s. Rhatigan’s visual language blends the grotesque and the tender and is leavened by the acidly self-deprecating humour of the captions and slogans – his posters and cassette liners are populated by cavorting or weeping disembodied cocks and the recurring figure of a naked, grinning, empty eyed sprite, the personification of an inner hectoring voice of desire and humiliation. Although his works deliberately call to mind crude doodling or graffiti, his line is careful, sinuous, even delicate at times, while avoiding preciousness. Drawing is a solitary pursuit, but this specific aesthetic, that of the hand drawn cover for a mix tape or a fanzine, is one used to create communities – in this case, one that pushes against the social taboo of loneliness and sexual insecurity.