Brian Maguire, War Changes Its Address: The Aleppo Paintings at IMMA

Combining institutional accreditation with extramural socio-political engagement, Brian Maguire’s Aleppo paintings game the late capitalist cultural commodity. Maguire’s mission – which could be seen, among other things, as a reformation of Francis Bacon’s indulgences – is an aspirational busted flush that attempts to insinuate forms of toxic human waste into sanitised spaces of influence and power.

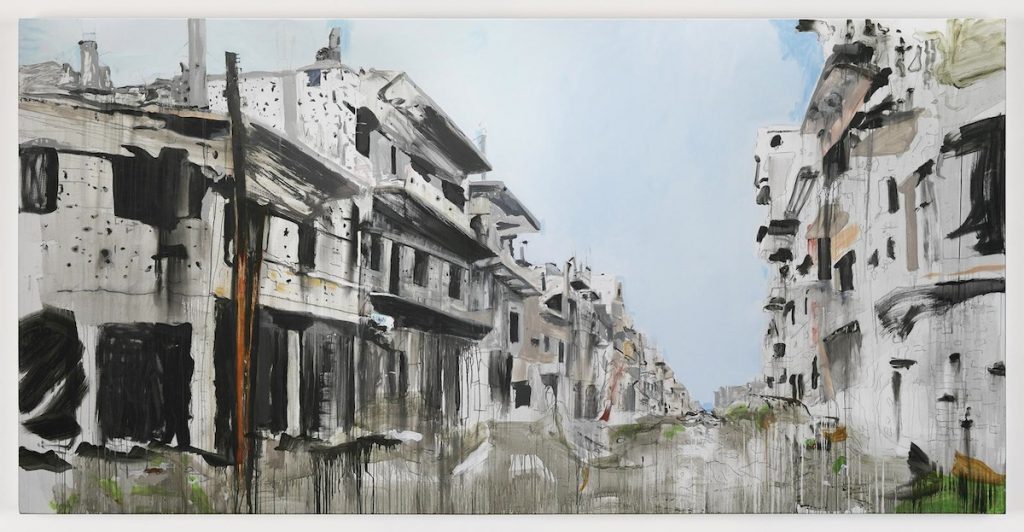

As a carrier of symbols, ruins are a disputed territory, coveted relics in wars of ideological legitimacy and justification. Be they prisoners, psychiatric patients, female victims of Mexican drug wars, or what’s left of the Syrian city of Aleppo, Maguire lines up his marks and strikes while the injustice is hot. Executed with clinical determination the Aleppo paintings leave the haggling and the handwringing to the collectors and the connoisseurs.

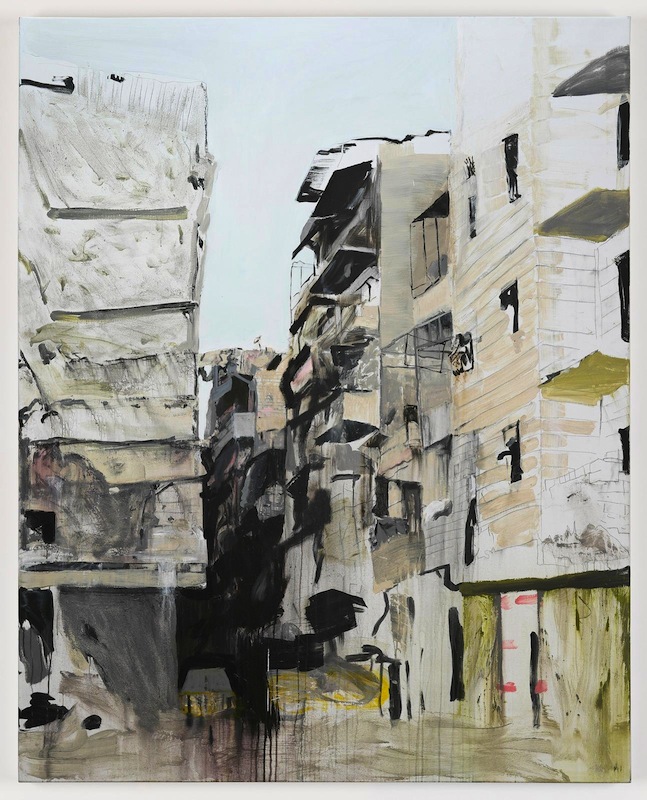

Maguire’s extraordinary rendition of a city’s impromptu monuments to its physical destruction presents us with a narrative in which modernity’s aesthetic aspirations, its harmonies, equanimities, and pristine sheen, are torn to shreds, leaving us in an endless groove of lacerations, gaping wounds, jagged mutilations.

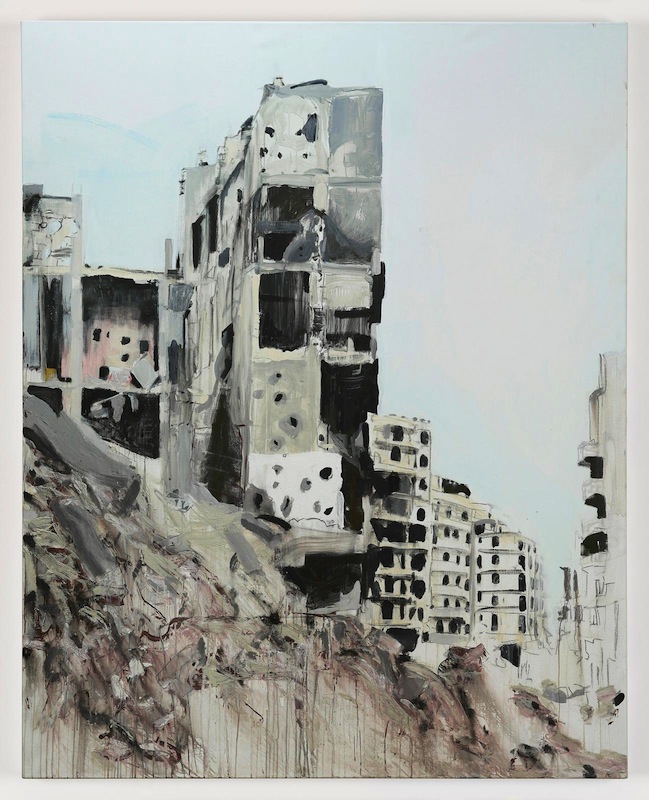

There is an insatiable hunger to Maguire’s output, the artist moving like a shark through international waters in search of fresh prey. In the Aleppo paintings the physical remains of conflict, habitations that have been bitten into and consumed by mechanised violence, are transformed into ravaged, and ravishing, altarpieces to a gutted humanity.

The marks, harried and irate, fall apart as quickly as they coalesce. The gnarled substructures of the paintings push through the images of ruptured concrete like bones through broken skin. Expanses of sky and patches of sun-soaked stone prevent the brushstrokes from collapsing into a heap of anguished howls.

While online ambassadors of injustice share their Ferrero Rocher pyramids of outrage and indignation, Maguire serves up the sacraments of an aesthetic mortification. It is left for us to decide if what we are tasting is something redemptive or the dregs of a murdered conscience – the ‘sneer of cold command… stamped on these lifeless things’ (Shelley, Ozymandias).

Maybe it will be a case of the violent bearing it away, with Maguire like Colonel Nicholson (Alex Guinness) at the end of The Bridge on the River Kwai, muttering to himself as the bunting flutters, “What have I done?”, then in a gesture of solidarity with the dispossessed, taking a Stanley knife to the commodities of his co-option, filling them with lacerations, gaping wounds, jagged mutilations.

In the anonymity and erasure of ruination a highly personal process of reflection is facilitated.