In my country historic memory competes for dominance in the mass subconscious with the constructed realities of media, specifically popular cinema. In the 1980s I noted that a ‘Reagan Youth’ generation having grown up on Rambo movies now fully believed that the United States had triumphed in the Vietnam conflict. Recently I read that a certain percentage of the American population regards the battle of Helms Deep in Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy as ‘historically accurate’. In the recollection of trauma, ‘special effects’ carelessly archived in our memory’s data banks often win out over fact. On the evening of September 11, having witnessed the attacks on the World Trade Center from the relative close proximity of the West Village, I described them on the phone to a friend uptown as “…a Nicolas Cage movie except that people are really dead." I immediately regretted hearing myself say this. Cage, who routinely survived fiery explosions in film after film, would be the necessary casting choice for the heroic lead in Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center (2006).

Willie Doherty’s exhibition entitled LACK at Alexander and Bonin Gallery is the artist’s most salient appearance at this gallery. A modestly scaled space by Chelsea standards, the gallery is located along a stretch of 10th Avenue and is a recipient of endless sunlight. The adjustment of your eyes to the gallery’s immersive darkness serves as a preparatory state of transition, physically and psychically, for Doherty’s installation of the fifteen-minute, two-channel video UNFINISHED (2010). On a screen to the left a male actor addresses us with a tale of abduction, imprisonment, and possibly execution. The man, age undetermined, performs this dramaturgy first sitting under studio lighting and then standing, speaking in a halting Irish dialect – the only feature of the piece to suggest that island. We hear of his imprisonment in what initially appears to be a vacant garage or storage facility – a very large, empty brick room. His words are pitched desperately, describing the anxieties of physical restriction and deprivation of visual information while blindfolded, divining clouds in the stained cement floor. Doherty’s actor internalizes movement while on the adjacent wall another camera roams the space like a caged animal. Several props make fleeting appearances – a knife with a crudely taped handle, a note hanging on a nail, and (unusually explicit for Doherty) a pool of dark red liquid begins to form. Nimble cross-editing mirrors details of the man (his ears, neck, and mouth) in relation to the restless pans of monotone brick expanses suggesting the journalistic trope of returning a ‘victim’ to the site of trauma for further on-camera registrations of anguish. Seamlessly constructed, UNFINISHED (a very distant cousin to Warhol’s raw Chelsea Girls of 1966) promotes unease not through the actor’s gesticulations, no scenery to ‘chew’, but in our application of sound to sight – spoken language to image. The individual’s story becomes disconnected; he bows his head awaiting a blow or bullet and repeated viewings did not help in forming a conclusion to his harrowing experience. The work may be indeed unfinished. Projected continuously, sadistic repetition always trumps ‘closure’, offering no final act signaling the time to move on – consequently any time one engages in the work is the right time. Our suspension within a maze of language in this purgatorial holding cell recalls Samuel Beckett’s comment to Jasper Johns while looking through drawings of his for inclusion in their collaborative Foirades / Fizzles publication of 1976, “…here you move all directions, but no matter where you turn you come up against this wall".

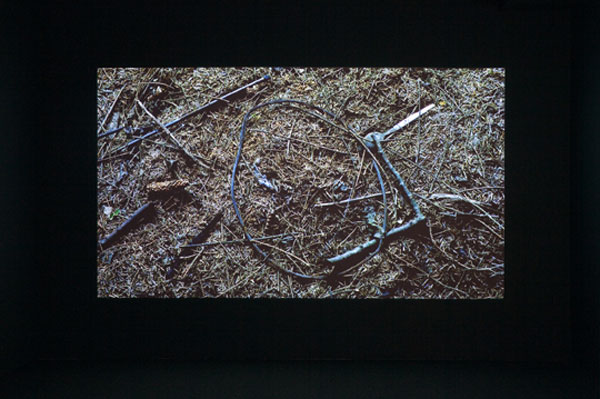

Passing from one gallery into the next we enter another ‘post – traumatic’ but marginally ‘natural’ environment. Projected on a single wall, the eight-minute BURIED (2009) catalogues the traces of man upon a forested area. We know the place Doherty’s camera examines; it is land forgotten, often awaiting promised renewal in rural, suburban, and even urban environs. It is the place of slow transience where unfortunate people build makeshift shelters, where the bad kids play, and where transgressions big and small occur. Jeff Wall often locates his meticulously assembled vignettes of dispossession in these ambiguous, but photogenic tracts outside the flow, and the law, of society.1 BURIED has no narration and is simply an examination of a temporarily uninhabited clearing of wood as daylight fades to night. The camera ‘gathers’ evidence and all signs point to some previous act of mayhem. The piece has a strong olfactory element – mists hang heavy and campfire dies out; we are shown rifle shells, a mask, plastic utensils, cord tied around tree trunks, and a unknown material melted across a branch. If the cement floor of UNFINISHED is hard and unyielding, the tree trunks and freshly turned earth in BURIED is alive with nocturnal life. The ambient sound design suggests civilization is not far away – droning noises and traffic can be picked up in the mix. Areas close to transportation routes acquire sinister histories as dumping grounds for biodegradable matter including people. BURIED, made a year before UNFINISHED, could be read as an epilogue to the later inconclusive tale; the open eye of a corpse awaiting burial would have shared perspective with Doherty’s camera in many of the low-angled shots.

Doherty’s video work of the ‘90s was prophetic in its employment of ‘real time’ surveillance technologies. The positioning of a camera upon any setting activates expectancy, transforming the innocent object or random encounter into the anxious. A useful comparison could be made between Doherty’s The Only Good One is a Dead One (1993) installation of two video projections with Bruce Nauman’s Dia Foundation opus Mapping the Studio (Fat Chance John Cage) of 2001. In the night-vision recording of his own deserted studio Nauman produces something (art) from nothing – a high-tech Zen meditation on the nocturnal movements of a cat, insects, and mice monitored as if housed in a bank vault in Las Vegas. In Doherty’s low-tech Good One we listen and wait, like for Godot, but no one arrives – a parking lot and road become empty stages for the paranoid narration and we transform from passive receiver to ‘witness’, a sometimes dangerous position to occupy. Doherty accomplished this same shift in meaning in his earlier photography which floated fragmentary text over formally composed images of ‘zones’ and territories such as the one in BURIED. Unlike our ‘picture generation’, Doherty developed outside the veneration of the Hollywood film still as lone template for the production of visual narrative. Behind the camera, both moving and still, Doherty has never elevated craft above the service to an idea. His directorial ‘style’ most resembles the docudrama form which accommodates, like in Errol Morris’ important The Thin Blue Line (1988), multiple narratives and viewpoints of a staged single event, passing the responsibility of judgment back onto the viewer. Jean-Luc Godard spoke about “every fictional film being a documentary of its actors."

On 15 June 2010 the New York Times published ‘House Hunting in Belfast, Northern Ireland’ followed on 18 June by ‘In Bloody Sunday Apology, a Promise of Closure’ (J. Burns). Walls may have ears, but to the relief of the housing market they remain mute. Here in Manhattan today’s vacant garage or storage facility is tomorrow’s blue-chip gallery. Willie Doherty’s art remains close to it origins while its relevance deepens, and scenarios are recognizable wherever a boundary is erected between ‘them’ and ‘us’. My own thoughts when visiting LACK turned to the current undeclared border war with Mexico and the incomprehensible savagery of the drug cartels which make other paramilitary operations look benign in comparison. In response to this our defenses escalate and our digitized eyes widen, waiting perhaps for that onslaught from the dark forces of Mordor.

Tim Maul is an artist and critic who lives in New York City.