Considering Matters of Occupying Digital Space – An overview of Fine Art Virtual Degree Shows 2020 in Ireland.

It is important to know the context in which the work is created, just as it is important to know the context in which it is received.

On the 12th of March this year, the art colleges across Ireland closed their doors. The students, with the support of technicians and staff, had just time to clear their space and gather materials. Due to the uncertainties of where their work was to go, what they were making or working towards and the unprecedented nature of the event, it was a gamble: how much dust will have gathered until they came back? How to get a productive understanding of what was experienced by art students and how this impacted on the work that was produced are some of the issues that I want to engage with in this piece.

Every year degree shows encapsulate the moment of live history that each graduating class inhabits. It is as if we were holding this moment in our hands, and if it is in our hands, how are we holding it?

The decisions that were made at the beginning of the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic by the art colleges of Ireland have had a profound impact on the social and material language of the students’ work. This dislodged student body of work can be understood as a diaspora: a moving, a scattering, a generating of migratory patterns as works dispersed then emerged, housed in digital rooms.

Just as galleries and museums around the globe moved quickly into the digital realm, so have educational institutions, placing themselves into the hand of the viewer. How is the work of fine art students held inside the screen of a computer, tablet or phone (these ubiquitous objects with no new experiential or material language)? The parameters of the viewer are changing between audience, participant, and reader: all intermingling as roles are being fulfilled through engagement with the digital platform. The nature of what is being viewed changes radically. Where once a viewer was positioned in physical proximity to an art object, now the viewer can’t transition or move through anything to change context: the image exists solely on a screen. Even now you are reading this text on the same screen you are viewing these graduate showcases, the same screen your emails are written on, the same screen you watch TV, the same screen you have used to walk virtually through the National Gallery. All of these moments are happening on the same stage.

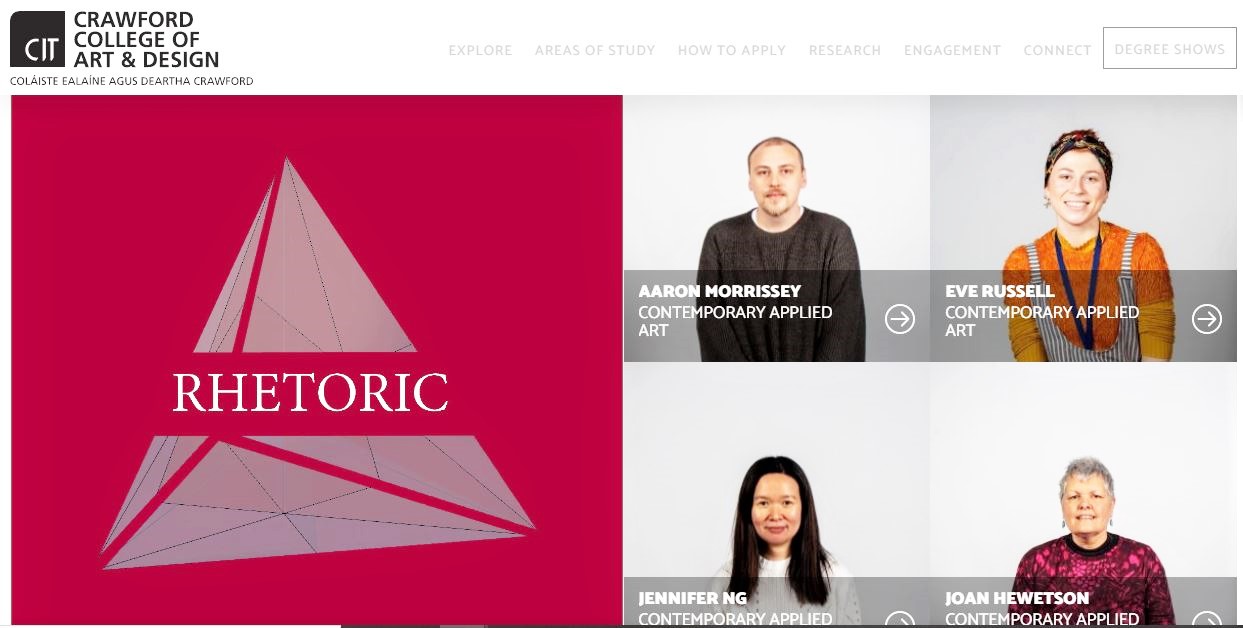

Art colleges adopted different strategies to showcase graduates’ work. I looked at the decisions made by four art colleges in the Republic of Ireland. The approach taken by the Crawford College of Art & Design, Cork was to create a digital showcase platform on their website where one is met by individual images of all their students, a large class photograph: a collective, a personal face. From the images of the artists themselves you are presented with a statement about their overarching practices and some stills or video of completed work. The college faculty created their own degree show Instagram account, a host space for this year’s graduates and, during the countdown to the launch of their virtual showcase, released posts on each artist and a statement about their practice. This space acts as a catalogue, as a mark of their graduates and an overview of the themes and methodologies employed by them, not an attempt at replicating the physicality of the degree show.

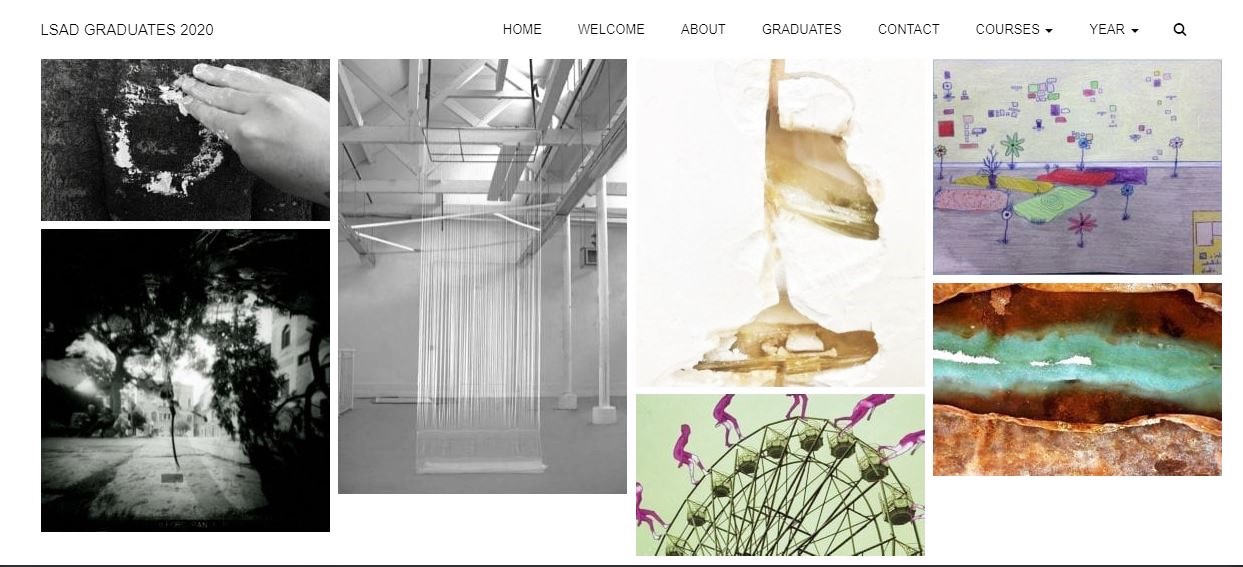

Limerick School of Art & Design graduate showcase exists mostly as a website, hosting artworks aimed at creating the atmosphere of a finished body of work, close in curated content to the selected works from each individual practice that would have been installed for the show itself. They chose not to create individual profiles or images of the artists on their website, keeping it focused on a portfolio of the college and a graduate body of work from each student. Instead of creating an Instagram platform it was the space of the everyday college platform that was occupied. They also hosted a miniature physical exhibition with the support of Limerick City Gallery of Art which opened on 15 July. Thirty-three fine art students displayed work in the gallery. Each student was able to install one small work that would either have been part of their degree show or that acted as its representation. The exhibition acknowledged the need for physical space. Ironically the restrictions on what could be displayed shared constraints of scale and interaction similar to those offered by the digital stage.

Both colleges presented their approaches as a ‘virtual showcase’ which implies a virtual simulation of the physicality of the show, but as you move through these websites the sensations are flattened, with images often shown in close-up. Out of context, the works are reduced to rectangles, without the physical proximity from one to another, no positioning on the walls, no floors to occupy.

There was also little consideration for the specific requirements of sculptural works, time-based performative pieces or any work whose existence depends on a tactile paradigm. Unfortunately as each college moved to meet the challenge of what they could provide their pandemic graduating class, the decisions seemed to favour those whose work was sympathetic to the digital medium and who already intended to showcase their work on a digital platform such as animators, graphic designers and to some extent photographers and painters.

The National College of Art & Design Dublin chose not to launch a website of collated graduate work and decided to hold back and launch a printed catalogue at a later stage. Instead, they publicised select stories on students with short interviews on their Instagram account while building towards a form of showcase which launched this September. The website is purpose built, and is framed in the introduction written by director, Professor Sarah Glennie as an ‘expanded digital catalogue’. This phrasing and atmosphere of the website in general gives space to students, and acknowledges the complex and radically different conditions of making. Taking that extra time enabled the students and staff to put together a catalogue of events, podcasts, panel discussions, interviews, all to go alongside the individual student showcases, giving more engagement and dynamism to the viewer experience.

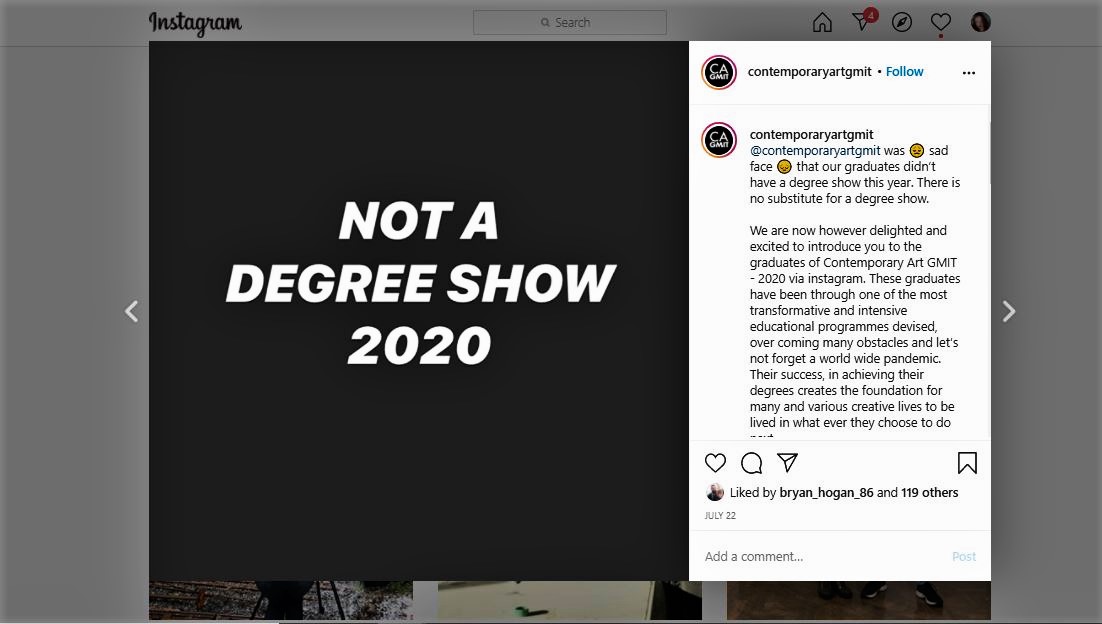

Galway-Mayo Institution of Technology’s Centre for Creative Arts and Media launched a digital portfolio, profiling the students and equally highlighting a focal point of their practice. But even as they produced this document, the title of their showcase, ‘Not a Degree Show’, best represented the undercurrent that prevailed in all the showcases this year. This graduate website was able to manifest as a physical exhibition, which launched on culture night 2020 on the 18th of September in Connacht Tribune Printworks

Variations on these modes of digital degree shows have occurred in countries all over the world, with students petitioning, lobbying and, in many instances, hosting their own physical exhibitions, declaring publicly that the kind of virtual space offered does not equal the experience and opportunities promised to them by their institutions.

From March onwards, with the closures of the colleges’ studios, students were told to launch the exhibitions digitally, they pushed for communication and information around the practicalities of the virtual alternatives proposed. As I read through the student accounts and gathered information from their perspectives, their concerns about the lack of physical materials, support and education were clear, it became increasingly apparent there were concerns about how to use this digital space, ordinarily hosting promotional material, advertisements for courses and communication with students and staff. Now the students had to use these same platforms in a personal and professional way, actively making and nurturing conversations and viewership on the threshold of a new understanding and a misunderstanding.

Articles have already been published that acknowledge and unpack the hurried choices made by the institutions. Two that have helped me frame this experience have been Remote Viewing by Morgan Quaintance and Communities of Care by Matt Packer. Why rush to produce a flattened experience rather than just a postponement? The question of postponement hovers above all the questioning glances and frustrated, silenced students who needed this moment as a catalyst to help them enter the professional world. But could they survive a postponement, and how much delay is respectful and productive to the fast-paced motion of recent graduates as they spread themselves in all directions to create work, are equally valid questions? There is no expectant time for us, and for that reason we need to learn from this year’s action in order to understand what we are working towards as artists, as students and as lecturers.

We have to look at what was put in our hands.

A common difficulty that was shared by undergraduates was the absence of support from their respective institutions to give them the necessary tools to occupy this digital space, thus preparing them for what viewers – or are they consumers? – are looking for. It is equally obvious that the digital realm has not been taken as a specific and distinct medium that had to be taught. It shows a palpable disconnect between the expectations of the larger institutions and what is/can be provided by the knowledge base of their lecturers.

But I think what also occurred is a very silencing assumption that the students will, can, and want to occupy this new kind of space. It is not just the degree shows that have been affected, since all contemporary art practitioners have been thrown into this space in a sink or swim manner, to find an original way to take up space on these ever-evolving platforms.

Of course, the adaptations required by the pandemic restrictions were simply an escalation of the general move by educational institutions towards remote learning and digital platforms. Some argue that the digitalization of the education system goes towards its democratizing education. YouTube, Zoom webinars, Lynda, and OpenLearn, among others, offer host spaces for educators to provide information for free. If the internet is a wary tool for educators, it is also presented as a way of empowering students to seek their own teachers, and teach others: information cross-pollination.

Many educators have long been concerned about what will be lost with the digitalizing of education. Covid-19 has accelerated this trend by presenting opportunities to test the limit of this model in real life as it were. An educational space should create a physical environment to protect and provide sites of exploration and opening conversations. It is about a space through which you can process ideas. Can all these foundational aspects of education be provided by digitalizing the syllabus or by lectures and meetings mediated permanently through a screen?

These limitations come into sharp focus with the degree showcases of 2020. The lack of physical exhibitions challenges the historical, theoretical and cultural progression of fine art that students have been preparing for during their undergraduate programmes/syllabi.

As I tried to understand this myself, graduating with a degree in Sculpture & Combined Media this year, I realized that for me the dissatisfaction comes from a sense of displacement: The artworks and students were left floating in cyber space without the natural conversations, connections and budding offers that usually fill all art college hallways at this time of year.

Positioning is a huge part of the graduate showcase: the site, the physical proximity and the juxtaposition of final pieces within the place of learning. The site of the degree show holds a specific resonance. The tactile resonance of memory is something held in the mind of the graduating class. There is a physical and narrative cyclicality to where the artworks go and to the context they are consumed in and the perspective of the viewer.

It is such an important tradition that the viewer sees the work connected to the language of their collective discipline. Rooted in their classmates, their studio sites, it is often the only time in their careers that their works will be installed and categorized by what they have studied. There is the feeling of collective understanding between these students: how they have learned and fed in to one another, how they connect and diverge, how the issues and feelings of their years in education are isolated and suspended in the historical marker of their degree show. And what stands out for me this year is a lack of unity. In a year with such global and collective experiences, the classes were disconnected and dissipated suddenly, and were not able to construct an encapsulation of this years’ feelings.

Without the physicality of the site and the proximity of the students to unify their experiences, the showcase stays as individual documentation of artistic practice, not as a graduate exhibition which as artists, students and viewers/consumers of contemporary art we look for. Bracing ourselves for another wave, the reality is that the potential of a public degree show may not come around as normal in the next year either and that lessons must be learned from this year’s outcomes.

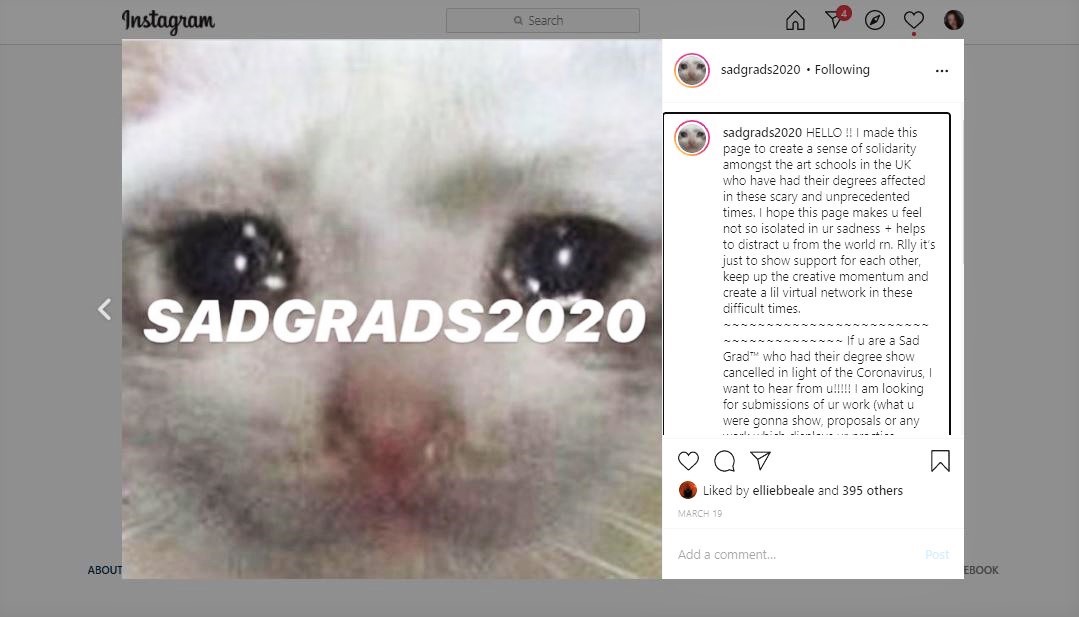

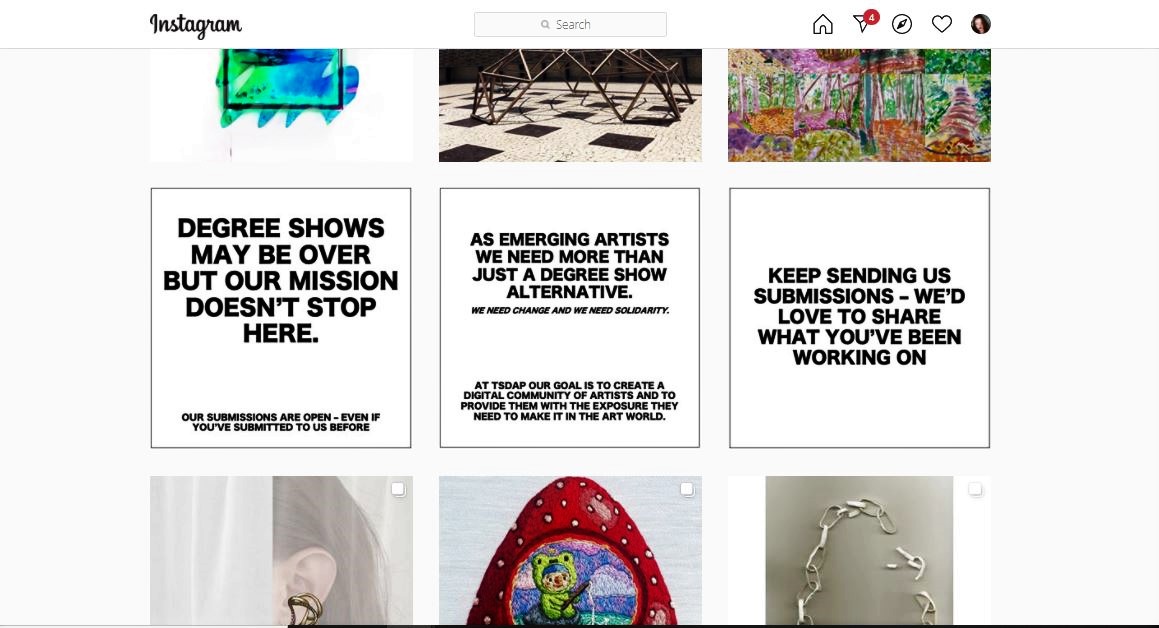

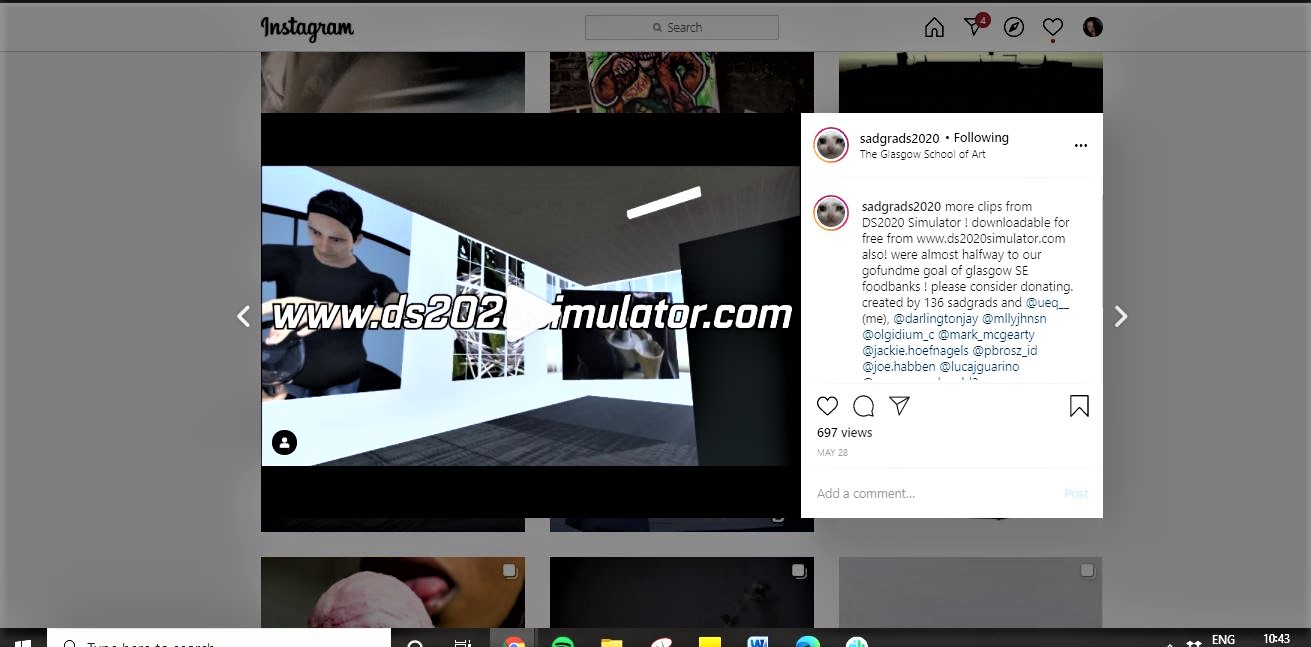

It is interesting to note that some of the most creative responses came from the student-led Instagram profiles, digital and physical exhibitions, zines and other creative projects that have grown through these digital spaces organically. For example, Instagram was used as an active platform where more natural communication between peers took place.

Specific kinds of creative practitioners, such as designers, shared their skill-set to generate original digital materials, and this communal spirit is coming through these woven digital spaces. But even here, as the conversations and the simulations are freer, the dissatisfaction and the mistranslations are present. The emergence of the student-led degree show is a positive move of ownership over how graduates wish to communicate with their viewers, but it is ultimately an action coming from frustration and dissatisfaction with what the institutions have delivered. In some respects, we have surrendered control of our image and our content. But while, for the colleges, the material was collated to serve as marketing to future students, it was heartening to see these student-led platforms connecting and building a network of students who were all trying to create work in unknown circumstances. Offering proof that it could be done differently.

These student-led projects – mostly growing on Instagram – operate in a myriad of different ways, mostly with open-call policies where students from colleges all over the world can display together and be seen and supported by one another. (There are some links at the end of this article)

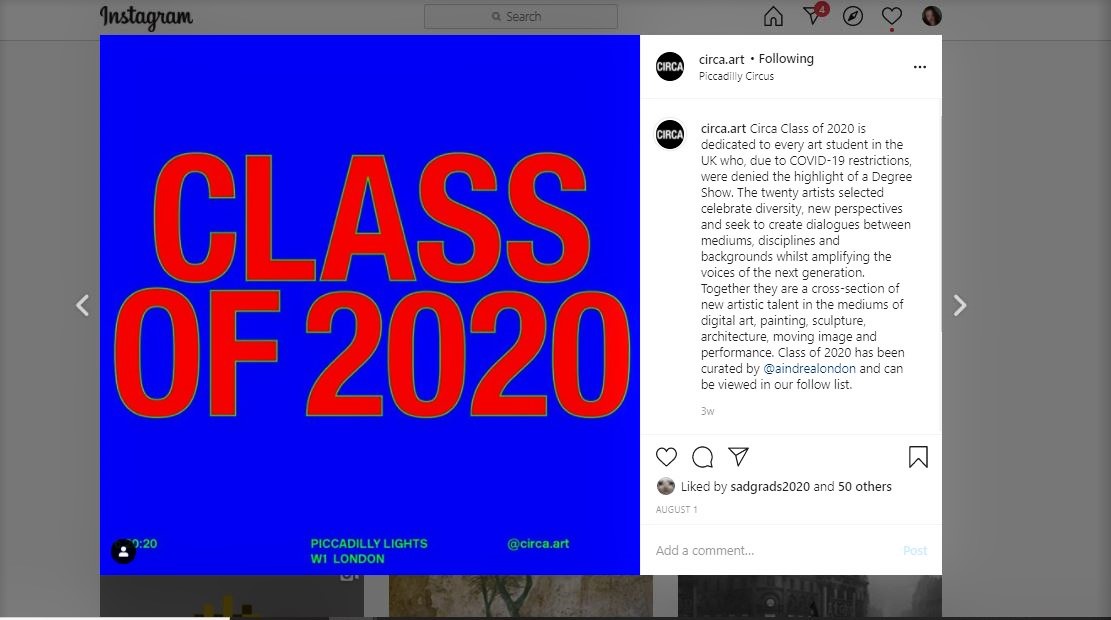

These social media accounts and websites were created with the language of solidarity, gathering thousands of followers and generating new digital conversations. This energy has also propelled them towards occupying physical public spaces in different ways, such as the collaboration between the London-based project CIRCA – not this magazine – and sadgrads2020 Instagram account who merged to create the month-long project to support graduates. They have been displaying a selection of graduates’ works on the Piccadilly Circus screen for two minutes every day at 20:20 BST/GMT. This showcase continued until the end of August with a group of eleven students selected by the sadgrads2020 account.

We need to draw on these ideas, this student-led momentum, to create reimagined digital spaces that students can learn about and activate with their work, but we also need to hold tight to those pieces that don’t make it through the screen and find a way for the tactile and haptic languages that are so fundamental to the arts to stay supported and active within these restrictive times.

In order to progress, we still need to hold, to touch.

I hope this article forms one of many pieces exploring what needs to be created and reimagined for subsequent graduating classes and artists during this time.

I dedicate this piece, to my classmates, and all the graduates of 2020, thank you for making through this.