Samantha McKee (1975) and Lisa Malone (1977) chose the above title for their respective sets of installations displayed in the B Wing of the old decommissioned jail. Unless we follow a Bahai view that “god created all humans from the same stock," and unless we ignore the huge differences sanctioned by religions, politics, tribal, national and racial customary insistence on their significance, the statement that we are now the same provokes disagreement and questioning. Since Plato’s Timaeus, in our culture sameness is the respected Other of a difference. Sameness could denote the lowest common denominator, or more luckily, coherence and agreement, fortitude and moral principle. The installations etched a drama of sameness over the narrative of the jail, over the gloomy darkness of the corridor between the rows of cells knitted together with suicide nets on each floor. The open doors of the selected six cells became harbingers of an uneasy state in between those who last opened them to get out and the art objects that now had entered. I meant to say that, in contrast to the prisoners, the art objects entered the cells willingly. The tension between sadness and play forbade me to do so.

Usually, an individual’s readiness to receive an art experience influences the nature and extent of its impact. In this case, the accessibility of art was deliberately impaired: by placement, by scale and by light.

The art objects in each cell and those suspended from the nets appeared to hide as if to avoid some sort of persecution. An unsuccessful desire to escape saturated them with a fatigue that paralyzed their energy, thus producing the stasis before the last escape.

McKee’s The Keepers and Malone’s A Short journey embody the states of body and mind of individuals entrapped by external forces.

In The Keepers McKee, for example, included a brain in a jar; it anchors the torment of individual consciousness in illness and near death.

Malone peopled the suicide nets of the jail with small steel cut-out figures journeying from darkness to the light, in an oblique reminder of Plato’s Myth of the Cave, about consciousness growing out of darkness towards the light of the truth.

McKee positioned lacquered shiny dark seaweed onto walls and floor, embalming the space with red light that was hurtful to the eye. Arranging the seaweed as crawling organisms accentuated the dilapidated condition of the cell’s surfaces and convincingly swapped the room for a kind of tomb.

Death is only a thin layer of breath away. The handwritten messages can communicate with the living only if they are read. This viewer could not get near to them to decipher the words.

Hauntingly, the artist described her installation so:

THE KEEPERS in cell have crept out of the mind and mutate into an ever more threatening presence to intimidate and torture, wreaking havoc in the mind. This is ‘the night watch’ under the inescapable intrusion of blazing red light. The final cell THE DEAD AND THE DYING is ‘when it all comes to head’ and the ending looms. The annihilation of self.

Not just a salient drive of imagination, those words are grounded in McKee’s own experience with those conditions and treatment, both chasing the same result by default.

Drowned in red light and obstructing direct recognition, the details stay detached, while domineering the thoughts and feeling.

Thoughts are given a cell on its own: THOUGHTS IN CHASE is immersed in a blue light and consists of twenty-eight white pillows with ceramic pieces of variable sizes glazed black. Each carries a stamped word – not legible from the doorway. Almost centrally positioned is one pillow pierced by a metal spear. Stamped on the aluminium is the word ‘Indifferent’.

In western paintings, the blue hue has been often associated with the heavens, contemplation, peaceful mood, and abstraction. To some degree, the mood of this installation remains contemplative, until the eye registers the violence inflicted by the sharp spear onto the pristine, white, comforting shape of a pillow. Nevertheless, the above-mentioned indifference saps the resolve needed to stop the violence. McKee has unearthed the passivity in the blue colour and the blunt impact of a violent detail. She makes it into an embodied critique of solipsistic thought and the popularity of violent games and films and newspaper stories.

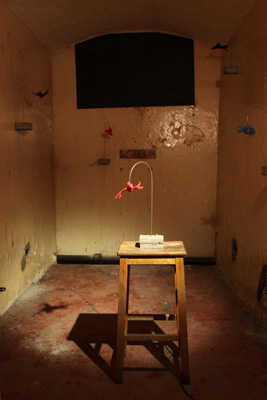

Lisa Malone champions activity, in the majority of cases, without movement. Her ‘people’ stand on impossible bridges ready to cross over or to enter empty cages; they balance precariously between and above the nets, tiny specks of bodies focused on some toil in utter silence. The one movable bird is tethered to a pole not to fly away, only around and around, forward and backward.

The metal and wire sculptures appear in the directed light as black-and-white drawings in space. The other objects are joyfully colourful, as if trying to induce the mood of a merry-go-round or a carnival. Interesting use of light, either static in the cells or moving like a searchlight over the steel cut-out figures, adds a theatrical layer: now you see them, now you don’t. All are actors in an unknown and unfinished story.

Ambiguous time, anonymous people in a resolutely strictly defined space construct a paradox, further enriched by the elements of weightlessness usurped from the comedy of life. The figures suggest a movement, but do not move. They exist, but do not say when. Driven like robots, they claim to be of nature. Faceless, they elicit sympathy normally addressed to individuals.

In response to the site, the installations obey its layout, take advantage of it, acknowledge its past, but the art objects, found or made, are not site-specific. Someone wrote recently that venues respond to art. The old jail certainly responded to the additions, and changed a little. The art of McKee and Malone made that small transformation visible and tangible. These art installations intensified the dramatic history of the place, without illustrating or denying it. In that sense the history and the contemporary art, the past and the present, were set into a calm parallel.

Moreover, as a commentary on the object theory of art, this art takes sides by emphasising intrinsic value. The matrix of making and thinking, of designing and placement, of closed form and formless light, is a true descendant of Leonardo’s trinity of eye, mind, and hand. The result is not a classical catharsis, it is just a convincing experience of the excruciating need to think straight in extreme conditions. In a free paraphrase of Lionel Trilling’s famous thought, this exhibition reminds me that the primary function of art is to liberate an individual from the tyranny of the past culture.

Slavka Sverakova is a writer on art.