The bonus of participation on social networking sites like Facebook, Bebo or MySpace is that it seems that there is life beyond the blog that nobody reads. Rules seem like they can be broken, pop charts can be manipulated, city parks can be renamed. You may be be just one of a billion satisfied users functioning within given parameters, but at least your friends know your every move. Social habits have evolved happily over the past decade towards a more online personal presence, with the prospect of endless love or serial monogamy just a few clicks away. The lonely-heart columns in the papers have long been replaced (and supplemented) by telephonic and personal online profiles where brevity is no longer a problem, and truth is far from the issue. In this spirit, Padraig Robinson’s exhibition at Monster Truck presented a number of signs from the way we fall in love and then die online.

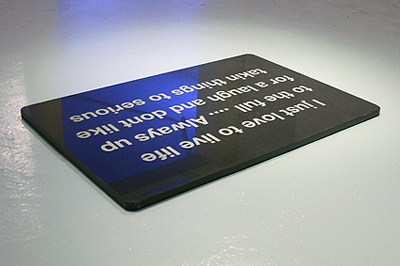

An engraved polished granite slab on the floor in the rear gallery, Virtual mortality (Bridgend), 2008, bears the rather benign teen epithet of “I love to live life to the full…Always up for a laugh and don’t like takin things to serious.” The text is from the Bebo profile of Kelly Stephenson, the sixteenth of twenty-one teenagers to commit suicide from the Welsh town of Bridgend since 2007 – allegedly all connected through the Bebo social-network website. What were described in the press as copy-cat hangings seemed to reveal a dark side of the normally banal tweenie postings. The subsequent Internet-suicide-pact media frenzy never got to the root cause or proved a connection or that indeed participation equals death. Robinson marks the moment with an anonymous gravestone, lying on the floor, a memorial of sorts but also oddly optimistic.

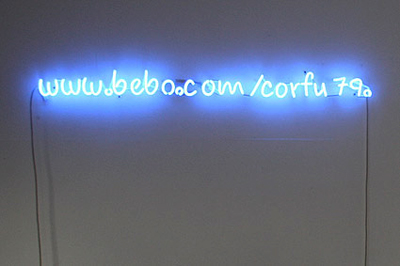

The word ‘unfriend’ has recently entered the dictionary – the term used to unlist ‘friends’ on Facebook. What is particularly interesting about this activity is that it is only known to the user as the unfriends are not notified, they simply disappear. Robinson’s baby blue neon URL www.bebo.com/corfu79, 2009, in a similar way deals with this kind of unrelationship. Here the work needs to be activated by going online as the piece exists between the real and virtual worlds. The site shows fairly average holiday snaps from the ’70s, dark, faded, with that magenta and mustard hue. Generic shots of the lush Mediterranean resort and surroundings do, however, include the occasional single male sitting in a café, at a beach or standing by a doorway. There are two different men photographed, each appearing alone, and Robinson has concluded, by implication, that they were probably a couple. Despite the holiday atmosphere, there is something rather melancholic about the images. The isolated male figures show a certain isolation of this gay couple, privately stepping outside the crowds of families and other hetero couples and families on vacation there too. Documentation of gay lifestyles, even this ordinary are rare and it’s sadly understandable that the album ended up in a flea market where it was purchased by the artist. Robinson’s twist on preserving the album is twofold – digitising the photos and placing them on the tweenie Bebo site for perplexed kids to wander into, and also burning the physical evidence and presenting the ashes in the gallery in a small Perspex box. This re-presentation and destruction mocks the earnest memorial but points to the positive collective amnesia that mainstream culture has for ‘the gays’ despite its wholesale appropriation and commodification in the past decade. These holiday snaps now join the millions of other random anonymous moments of life presented online. They are not so much remembered but now exist unrelated to any specific people, unconnected to family, friends and each other, reflecting the lost lives and relationships the photographs once documented.

The exhibition turned the small, feverishly whitened galleries into a neat minimal mausoleum shared also by a human skull and concrete slab with book. If we think of the beautiful bloated binary of sex and death, and how it was ruined and ravaged by contemporary art, Damien Hirst instantly comes to mind. It’s difficult to know how he can be critiqued as his work is beyond pastiche at this stage of Nth repeat and re-make of the same old formula. The sheer cynical market and media manipulation that surrounded the For the love of God, 2007, diamond-encrusted platinum skull needs to be remembered, however. With Robinson’s juvenile take on the macabre, Coco Pops have replaced gems on a plastic skull which, as the statement said, is all “at once serious, adolescent, dark and annoying.” The chocolate breakfast cereal gives the work an oddly metallic rusted appearance, looking pitted as if dug from some archaeological site but certainly not at all edible and not very child-friendly either. The work presents evidence of spectacle of death in art but re-appropriated in another kind of disrespectful material.

The final piece in the show is rather a beginning than an end. It is the start of a possible project that extends into the paranormal. For Rory, 2009, is a concrete-frame slab containing a black book with the title embossed in sliver. Robinson was contacted by his mother who had talked to a psychic who said a spirit called Rory was trying to get in touch with her son about his work. The resulting work is a hermetic and private piece, as every page is marked with an ‘X’ by people Robinson told about the story. But with the book surrounded by concrete and on the floor it does not invite opening. After the show closed Robinson went to visit the psychic who turned out to be a stocky GAA-type lad, not the stereotype of a turban-wearing, crystal-ball-stroking charlatan. It transpired that Rory was a red-haired gay man from Bristol who committed suicide or died tragically in the 1930s. The psychic offered no reason as to why Rory was trying to get in contact with Robinson through his mother, but the coincidences with the project are just too good to ignore. The piece itself, without knowing, becomes a form of condolence book, marked by people who know the story not the person. The spirit world could be aligned with the virtual world as both are unseen, both left-over bits and pieces of real lives. The different forms of memorial in the exhibition draw out these different intangible aspects of identity, moments of tragic biographies and forgotten lives that may or may not have existed. However, there is no fiction with these works, they are rooted in the real but obliquely presented in several different dimensions, merging unfriends, real friends and strangers.

Alan Phelan is an artist who lives in Dublin.