|

| Lorraine Burrell: Greet the day, 2006, installation shot, Arena supermarket, Askeaton; courtesy the artist |

From time to time an exhibition succeeds in stripping contemporary art down to its most basic precept – that of engagement. Curated by Michele Horrigan as part of the first Askeaton Contemporary Arts Festival, Welcome to the neighbourhood is one such exhibition. The exhibition features an eclectic mix of ten national as well as international artists, all outsiders to the quaint town of Askeaton in Limerick. Such a disparate, though interesting, combination of artists, together with the removal of the exhibition from the usual comfort zone of an urban and gallery based environment, admittedly initially fuelled both excitement and reservation.

With the exception of a few video pieces, the artists created site-specific works, all of which in some way or another depended upon interaction with the community. While video can be a sealed medium, the video works begged to be engaged with, particularly Vito Acconci’s Open book from 1974. Acconci made his mark at the height of ‘happenings’ and live performance art in the late sixties, challenging perceptions of public and private space. In later works Acconci attempted the difficult task of engaging the viewer through the medium of video, drawing the viewer into his (unreal) space. Sited in the Civic Trust, Open book is a close-up of the artist as he attempts to keep his mouth open while imploring the viewer to come inside. Barely audible phrases are repeated “I’m not closed I’m open…I won’t trap you,” and then when his mouth accidentally closes momentarily he implores forgiveness from the viewer. Drawing the viewer into the artist’s intimate space, Open book is simultaneously compelling and repelling.

Engaging in a more subtle manner is Lorraine Burrell’s Greet the day . Screened in the most public of places, the local Arena Supermarket, Burrell’s documented performance places the artist in various different vulnerable situations from a lighthearted perspective. The strength of the piece relies on the viewer’s ability to empathise with the commonplace embarrassing situations. Less reliant on the viewer’s response is performing artist and singer Laurie Anderson’s mid-1980s video What do you mean we? Anderson’s video piece sits comfortably amidst the animated conversation of the locals in Cagney’s Bar and Lounge. The comical yet philosophical work depicts the artist and her three-foot-tall male clone, who has been created to ease some of the creative burden. In the farcical clone Anderson creates an alter ego of the performing artist. The technical tricks and high-contrast colour are dated, though Anderson’s ability to captivate an audience is undiminished.

|

| Jeanette Hillig: shopfront installation shot, 2006; courtesy the artist |

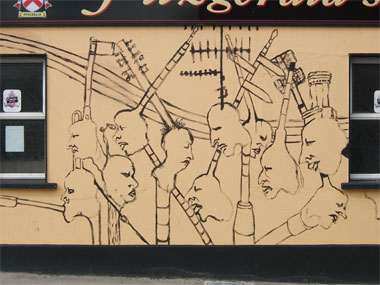

The demesne of the locality provided inspiration for the remaining artists, some creating their works on-site. Jeanette Hillig combined household and found objects into her sculptured forms that are as curious as they are playful. Hillig’s colourful, abstractly painted window, with found objects incorporated into the display and illuminated by a fluorescent bulb, proved her most powerful work, providing a visual impact to the traditional shopfront. Similarly Paul Aherne enlivens a defunct building with his stream-of-consciousness drawings. His impulsive inky drawings invert the perception of graffiti as urban defacement and bring an energy into a quiet corner of the town.

|

| Paul Aherne: Fitzgerald’s Sportsbar, Askeaton, 2006, installation shot; courtesy the artist |

Swedish artist Ilja Karilampi created an installation at the local hair salon from a mish-mash of cultural references, using drawings, text and magazine cuttings. Upon entering the installation space, viewers were treated to an impromptu performance where the artist re-enacted the everyday ritual performed in the salon, as he swept up masses of hair from the floor. Karilampi revealed an acute awareness of the repetitive patterns of activity within the space. Recurring patterns are also uncovered in the suburban sprawl of endless identical housing estates as explored by Sean Lynch in Tales from the suburbs . Lynch’s postcards of Limerick’s suburbs question the idyllic life promised by property billboards, and indeed reveal these empty promises. Direct interaction with the community tightly binds the exhibition to the town itself.

|

| Ilya Karilampi: installation shot, Askeaton hair salon, 2006; courtesy the artist |

Michael Eddy created a ‘welcome’ sign upon entering the town, which consists of a group photograph of Askeaton locals. While the sign itself is unremarkable, the process involved in taking the photograph forged a bond between the artist and the community. Doireann O’Malley likewise engaged with the inhabitants and locality of Askeaton through the medium of photography. O’Malley’s photographs of the peripheries of the town project a remote though industrialised suburb, while her portraits of individuals living and working in the town are more resolute. Fixed in their specific time and place, O’Malley’s photographs give recognition to the multiculturalism permeating the traditional fringes of society.

|

| Michael Eddy: roadsign on the edge of Askeaton, 2006; courtesy the artist |

Carl Doran’s work perhaps most directly engages with the public, as it required building a relationship of trust with the residents of the town. The public was invited to donate broken yet cherished personal items to the artist. Doran strips these objects of sentimentality and originality, depicting them as interesting forms and shapes in a series of immediate, raw drawings. An important part of the work was giving a drawing to all who generously donated items. The heart of Doran’s work, like that of the exhibition on the whole, lies in act of reciprocation.

|

| Carl Doran: performance shots in Askeaton, 2006; courtesy the artist |

The exhibition is not only an exchange of artistic ideas, but of knowledge, heritage and community pride. As part of the festival, artists’ talks and a tour of the medieval town’s rich heritage and historical landmarks further enhanced the creative exchange. In a society where increasingly we do not know our own neighbours, this exhibition proves that it is still possible and indeed valuable to reach out towards others in a gesture of neighbourly hospitality. Welcome to the neighbourhood forms a symbiotic relationship between the artist, viewer and the town of Askeaton, each nourishing and enriching the other.

Karen Normoyle is an art historian and visual arts writer.