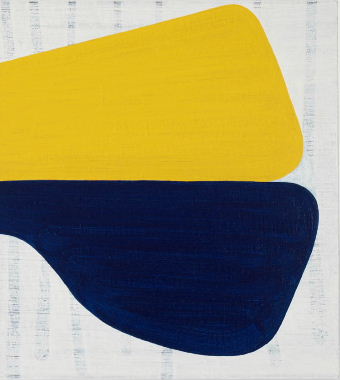

Hazily, I recall that there was a painting called Synthesis early on. The title now embraces a body of work from the last three years, a selection assisted by two galleries: Rubicon (Dublin) and Fendereski (Belfast). It includes a powerful composition with one yellow and one blue-black shape that mirror each other: Togetherapart, 2006 . On the level of abstract ideas this image is a key to more than just itself as ought to become apparent from the following e-mail conversation I had with the artist.

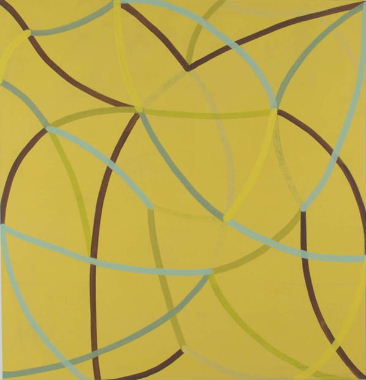

SJS : I take as a starting point the catalogue to your current exhibition, with the discussion between you and Joseph Wolin. On page 9 you think of the paint surface (not the painted surface) as a record of the process. The Yellow ribvault, 2004, is an example of mimesis noticed after the work was finished. The tree outside the window was there before, during and after your work was done.

This asymmetrical relationship between nature and art is significant for the freedom it offers. Before we immerse ourselves into thinking about neural-net responses to any stimuli, would you, please, describe, roughly, how some particular paintings in this exhibition are different records of the “type of touch"?

RH : I shall have to answer this question ‘roughly’ as it is difficult to describe the differences of ‘types of touch’ with any real specificity as there are infinitely subtle nuances that are for the most part subjectively perceived and that can only truly be gauged in the presence of the actual work. The factors involved in gauging the ‘type of touch’ include the amount of paint applied, its opacity, its solidity / liquidity, the method of application or removal (laid, poured, trowelled, rolled, dragged, pushed, pulled, etc), the type of tool used (variety of brush, knife, sponge, cloth, etc), the direction and also the speed.

Some painters use their material aridly, some parsimoniously, others bounteously, voluptuously, tenderly, delicately, crudely, violently, carefully. These adjectives generally arise from an assessment of touch and there can be no question that allied to subject matter this affects our response as viewers. My own types of touch as a painter, I think, generally exist within a narrow range that is relatively slow, measured and gently sensuous.

In a painting like Yellow ribvault, there is ostensibly a yellow ground with a soft horizontal drift against which contrasts the more purposeful directionality of the drawn ‘vault’ lines. In the flesh one can discern (due to their translucency) the ‘held’ brushstrokes which indicate the (relatively slow) pace and direction of each line; this evidence makes one re-imagine the construction of each successive line and for me this reveals a kind of controlled or dance-like set of component movements.

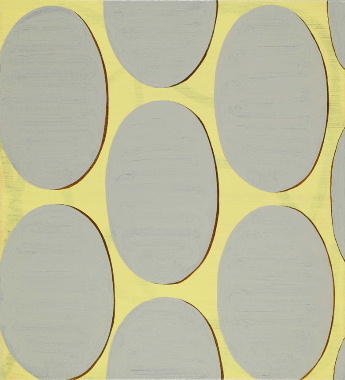

In Swarm, the almost-easy drawing of the wetly applied grey ellipses over their dark brown underlays imparts a certain anxiety (perhaps the trapped anxiety of me trying to physically construct the shapes, ie pushing a loaded brush around to follow the brown perimeter while struggling to ensure that the paint doesn’t misbehave and form globs that ruin the edge relationship between brown and grey).

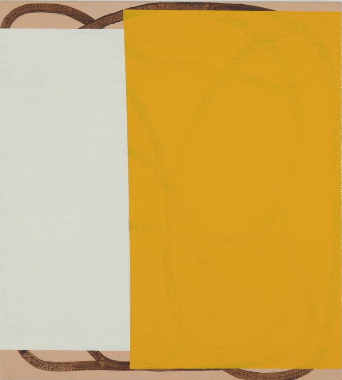

On the surface of Screen, there is a thick, viscous orange that could only have been dragged slowly over the surface. The succulent weight of this barrier contrasts with the relatively pacy energy of the linear underdrawing. Work rests on these kinds of tensions.

SJS : This rich connectivity between touch and other stimuli illustrates well the difficulties and delights a viewer may experience.

Tony Bartley ( Circa 64, 1993, p 54) states that in the then reviewed work you do not use metaphors or historical references. Nevertheless, he mentions one historical reference “absurdities arising out of the inappropriateness of contemporary notions of identity." His note on “spatial ambiguity" inspires a thought, contrary to his claim, that this may be a metaphor. I think of ambiguity born out of the culture in which you have grown up and lived as an adult artist. During your undergraduate studies in Belfast, how strong was the desire to develop an art practice that would step out of the inherited frame? What was the most helpful inspiration to do that?

RH : I think that one of the things that brought me to art was my upbringing as a product of a ‘mixed marriage’ in the Northern Ireland of the ‘Troubles’. From Belfast originally, my family moved to Kilcooley (an infamous loyalist housing estate twelve miles from Belfast on the edge of Bangor) when I was seven years old and we remained there until I was seventeen. To grow up as part of a quite hard-core Protestant community, all the while knowing that your dangerous ‘half-Catholic’ secret renders everything a pretence, and engenders a certain mind-set of skepticism, of questioning and of contrariness – quite useful qualities in art. Of course I also had to get over my life-long training of “whatever you say, say nothing," and I think all my work at art college (during MA too) tended to sublimate the deep-seated anxieties that I (and many, if not most, other people of my generation) held.

After art college, I had a bit more conviction about what my intentions were and the then theoretically fashionable climate of ‘deconstruction’ allied to my own natural tendencies formed the template for how I tried to dismantle the world through making art!

SJS : Speaking of dismantling… others do that in unwelcome ways. Colin Darke ( Circa 66, 1993, p 57) perceives your images shown in 1993 at the Rubicon Gallery as “an objective analysis of … war-torn Belfast" as “metaphors for the present conditions in NI." Your own comment weaves a narrative out of nouns like destruction, reshaping, deforming and displacing – all acts that happened to people and the city. I admit, I do not see it as an objective analysis. Instead, taking Residue III for example, I think of the heroic modernists dragging autonomous, disinterested art into the role of courageous and honest witness. Once you decided to connect the ‘all-over-paint’ model with an illusionist vignette, did you encounter increased demand on composition and key? Am I wrong in recalling the switch from dark key to high key?

RH : The “‘all-over-paint’ model with an illusionist vignette" was typical of the aforementioned template in that it was an attempt to simultaneously play with different models of visual language in an attempt to create, or expose, something new (or, at least, fresh). Templates are fine, but one still has the physical problem of trying to make something that works! Combining different types of imagery did create more formal demands, as you suggest; however, this didn’t always result in the use of a high key (eg Constructed heritage ). I think it would be more accurate to say that there was a move away from my previous predilection for low-key, or tonal, painting.

SJS : Peter Jordan ( Circa 76, 1996, p 49) perceives you as “expressive painter … fond of dark key and rich texture." You have dealt with the evolution of the colour key above. Jordan finds it difficult to establish what the meaning of your images is, and objects to abstraction as not adequate to “represent the multidimensional nature of the world." Is this why you included words, even if incomplete ones, and selected elaborate titles for the paintings, eg Emigrant landscape or Constructing heritage / Constructed heritage ?

RH : The paintings that Peter Jordan found difficult were not ‘abstract’ as such but were a series of works made by projecting photographic images of street crowds (a stereotypical image in film and television) and then painting / obliterating them in successive layers.

For me the use of these images was much the same as how I used text, ie, as a ‘sign’ – a fragment of language with a set of given associations but with room for movement due to context and (mis-)understanding. The method of constructing, or working with, these ‘signs’ was how I tried to form meaning and I generally veered toward meaning that was more poetic or multivalent (this is still true). With titles, I am also drawn to open-endedness rather than a more specific, or forensic, use of language. Titles can also be a way ‘in’ for people, or at least a stimulus to think about a work in a certain manner.

SJS : Gavin Murphy (Circa 114, 2006, p 71 ) notes the spatial ambiguity, the enigmatic titling of the paintings, and subtle interplay of textures, skill and awkwardness as means of a commitment to paint. While I go along with his observations, I am acutely aware of a shift between the early pre-MFA work, intoxicated with raw emotions, and the contemporary paintings like Illusion, 2006, which keeps the Dionysian principle firmly under the power of Apollo. The story is now not outside the image, it is it. It seems to be a command to look, to see, to think.

Where does the light come from capable of holding the high key even if an area is black? I have in mind Togetherapart, 2006. It reminds me of the daylight above the small harbour with the fishing boats in dark colours.

RH : With regard to the Gavin Murphy paragraph above, I don’t think of myself as having a “commitment to paint" – I have always seen myself as an ‘artist’ rather than as a ‘painter’ even though painting is largely what I do. If I have a commitment to anything in my work, it is to exploration or discovery.

Togetherapart puts together an almost black blue and a cadmiumesque yellow. I was trying, I think, for a ‘logo’-type image. When I was making that painting I was on a two-month-long residency at the Albers Foundation in Connecticut, and among some of the drawings I was making were some gas-station signs, and I’m pretty sure that that was the influence.

I hadn’t considered the now obvious fishing boat / reflection nuance (if that is what you mean) of this pairing, but would you believe that the residency’s 75-acre site included a private lake with a rowing boat for my use? (It was a facility that I availed of quite happily!) I think that it could be another example of an influence slipping in unconsciously (like the branches in Yellow ribvault )

SJS : Well – there is a problem with the word – abstraction in art has been perceived as nihilist, decorative, sublime and ironic. At its least sophisticated, people think of abstract art as art that does not depict recognizable scenes or objects.

I like the definition of abstraction in chemistry: it is a reaction or transformation the main feature of which is a removal of some everyday aspects that allow integration into a non-trivial abstraction. All such abstractions are to some degree leaky – they are full to the brim of tacit knowledge that resists explanation. These abstractions break an aspect away from its contexts and offer instead new concepts, new hypotheses … the explorer in you must cherish this.

Slavka Sverakova is a freelance writer on art.