In this three part essay, Susan Thomson explores violence and political struggle in moving image and film work shown by AEMI (Artists’ And Experimental Moving Image) in Ireland, at the ICA (Institute of Contemporary Arts) in London and at other international film festivals. In the first part, Reconciliation, she focuses on The Troubles through the work of Donal Foreman’s The Image you Missed which itself looks at the work of the documentary filmmaker Arthur MacCaig.

The ecological gardening of the women’s village is continuing and the first flowers and fruits are growing. There are plants of pepper, pumpkin, tomatoes, aubergine, potatoes etc. These are the seedlings we planted in spring. The Garden gives us many fruits. In society women are often seen as without force and weak. With the construction of the village of free women #JINWAR we are going to change this backward opinion and we will create personalities of free women. Already with the results of the construction we showed this. Women build their own houses. They live according to their own planning and fruits of their work. For this we are proud and are continuing our work with success. They may cut a flower but they will not stop Spring from coming.

– Jinwar – Free Women’s Village, Rojava, Syria via Facebook

It’s that tenacity, that kind of spirit that I’m really enamoured of…To turn it around and not to have been victimized. I mean it doesn’t erase the thing, but if you come out whole, if you come out no longer the victim in your own mind, then that’s great…I see many, the woman with the suitcase (in Soft Fiction), the woman on the train and the woman behind the waterfall at the end, as the traveller, the woman on a journey, the woman completing it all, the woman coming out the other end whole…and more than whole, with the addition of coping with experience and making it constructive.

– Chick Strand speaking at the Cinematheque 1980 Irena Leimbacher in ‘An Introduction to Chick Strand’

Ruben Östlund’s Palme d’Or winning film The Square (2017), an art-world satire, about a fashionable curator of a contemporary art gallery, features an (imaginary though now really existing) artwork called ‘The Square’, by a sociologically inclined artist who produces a lit square, its outline carved into the concrete of the grounds of the museum. “The Square is a sanctuary. Within it we all have rights and obligations”, we are told. The film mocks art world pretensions, including linguistic ones, making it a difficult film to critique, but it does seem as if the utopian, sacred space of the square is somehow a talisman, magically creating a negative (in both senses) space outside of its small dimensions in the world of the film, so that things soon begin to slide uncomfortably out of control. The scene which has most stayed with me is that of a young refugee boy (whom the curator has accused unwittingly of stealing his mobile phone, along with all the others who live in the same building) repeatedly saying “Help me”, as if he is trapped somewhere within the curator’s apartment building, or, as its insistent repetition renders the sound less realist, as if his voice is on an installation audio loop, in the curator’s flat. We do not find out what becomes of the boy, but it feels as if this is also meant to represent the voice of the curator’s conscience, finally breaking through in an otherwise superficial world. Does the film at this point simply echo a white saviour mode of thinking? Perhaps it also implicitly critiques museum practices of artwashing, whereby global emergencies, like the refugee crisis, are co-opted by Western institutions, thereby giving the latter a radical veneer, or where the funding policies of some institutions are sometimes completely at odds with works shown, such as demonstrated by ‘Liberate Tate’ from BP funding, or the recent controversy over an arms trade private function/radical left panel discussion double booking at the Design Museum in London. The world events and major upheavals of the last two years – Brexit, Trump, the rise of the far right, ongoing wars – have to be and are being dealt with by the Arts and it often can at least appear as if current events have indeed pricked the conscience of the art world. There has been, over the last year or two, an overwhelming amount of political and socially engaged artwork and moving image work on display at museums, large and small, for profit and not-for-profit, and at alternative cinema spaces. Works such as Democracia’s ORDER at Rua Red or Yvonne Rainer at IMMA (and MoMA too); in New York last year, Zoe Leonard was showing at the Whitney Museum and Adrian Piper at MoMA; a casual glance at the recent 2018 Turner Prize demonstrates current politically engaged priorities. And so many more. Is this more than virtue signalling or artwashing? Perhaps things are simply finally starting to ‘get real’.

This three part essay, will try to get beyond the knee-jerk cynicism and explore violence and political struggle in a variety of ways, focussing principally on moving image and film work – in Part 1: Reconciliation about The Troubles; in Part 2: Restoration about #MeToo (before the movement itself); and about Black Lives Matter, and the Feminist Revolution in Northern Syria in Part 3: Revolution. I will look at works shown by AEMI (Artists’ and Experimental Moving Image), founded by Alice Butler & Daniel Fitzpatrick in 2016, who show film and video in a regular curated series of events. AEMI screens films that otherwise can be hard to access in Ireland, particularly experimental cinema both old and new, and moving image work. I will also discuss a series of art events at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London. Stefan Kalmár, the relatively new director, stated in a recent article that “Herbert Read, one of the founders of the ICA, described in 1948 – 70 years ago – our institution’s goal as being one for the advancement of society.” Though perhaps one would no longer use this type of language, his mission seems to be to continue the spirit of this statement. I will look at the events of the ‘In formation III’ series. The works examined in this essay look at loss, censorship, dialogue, anthropology and how political matters are represented in a variety of forms, and in the third part on ‘Revolution’ there is my attempt to restore content to one of the blank spaces of the contemporary moment and media landscape.

Part 1: Reconciliation

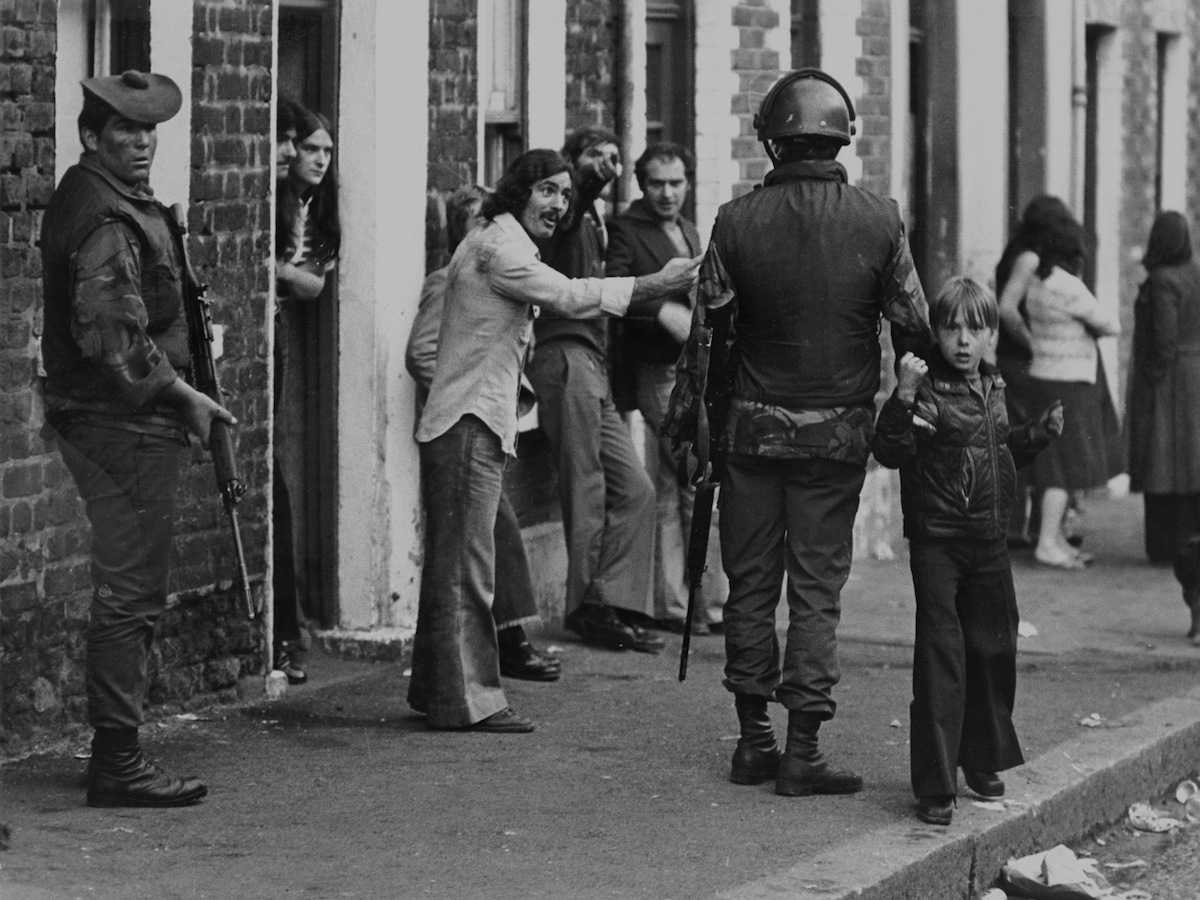

Donal Foreman’s The Image you Missed (2018), is a lyrical film essay about his father, Arthur MacCaig, documentary filmmaker who made many films about ‘The Troubles’, and whom he met only twice in his life. The film uses scenes from MacCaig’s archive to navigate both the political situation and personal history. It is in a sense a film restoration, an intertext. The film’s titles credit father and son as joint authors: ‘A film between Donal Foreman / Arthur MacCaig’. A vertical line divides them, a partition. The film brings MacCaig and his work back into the spotlight, softening the hard edges of ideology, making the work more palatable for a post- Troubles, post-Good Friday agreement, postmodern audience. MacCaig has no say in this authorship however, he is a ghost author here, and he gives no consent, though Foreman believes he would have been fine with it, since for one thing it gives more exposure to MacCaig’s films. The film does however take MacCaig to task in a number of ways: as traditional, ideological filmmaker – the shot/reverse shot of traditional cinematography, seen here as representative of binary, ideological struggles, even sectarianism, or emotional coldness, is undone here – and as a father. The double authorship is evoked in a number of ways, and to emotive effect: ‘match cuts’ are employed a number of times, such as the jump cut in time and space between Foreman’s childhood film, wherein a boy falls out of a cupboard zombie-like, covered in fake blood, cutting sharply mid-fall to MacCaig’s Troubles footage of a man walking out of a door covered in blood in Northern Ireland. The fake blood turns real mid-shot in an unexpectedly chilling manner, bringing a literalness too to the notion of a cinematic ‘cut’ – the wound between son’s film and father’s film – as if this new, jointly authored film were articulating a psychic wound.

The film is voiced by Foreman, telling the story of his relationship (or lack of it) with his father. During the edit, Foreman explored other narrative possibilities, such as staging a conversation with actors, before returning in the final version to this more traditional method of the voiceover, but it works effectively. If the film acts in some way as a mirror, it is nearly a mise-en-abîme. It appears to trace a predominantly patrilineal history, as we learn also of the great, great grandfather, who left Ireland due to the Great Famine several generations earlier, a man who seems to boomerang back in the shape of the American father, MacCaig, who devotes his life to documenting the Troubles in Northern Ireland. The film feels like an attempt to get to know or even maybe to impress the father to whom he could never get close in his lifetime. Foreman’s mother appears a deliberate absence in the film, though his parents’ letters to one another are voiced by actors, seeming to echo the voicing of IRA and Sinn Féin leaders by actors, as depicted in a short film Irish Voices (1995) by Arthur MacCaig shown before The Image you Missed at the ICA. Many other stories remain untold in this lean film. We never discover within the film that his mother too was a member of Sinn Féin, for example. In this most feminist, ‘the personal is political’, approach to filmmaking, it is perhaps strange to have the subject matter so dominated by men, and there is a danger too in glorifying the absent war photographer/filmmaker. The story is told with a certain detachment – whether this is a Brechtian aesthetic decision or a coping mechanism – ultimately to moving effect. The soundtrack too features a layered, palimpsestic, textured approach, combining archival sounds and noise, in a non-realistic manner, as well as some funky, electronic music which seems oddly appropriate. When viewing MacCaig’s The Patriot Game (1978) (shown as a double bill with The Image you Missed at the ICA, London – a loaded place to screen such films – and prior to this at the IFI, Dublin) the music seems to echo in The Image as an updated version of the refrain used in MacCaig’s film. The Image you Missed offers space for contemplation and meanders a little like Foreman’s fiction feature, Out of Here (2013), in a way that allows the viewer the space to think and feel.

The film also frequently freezes when it finds an image of his father (and these are rare in MacCaig’s own footage). Time stops, an emotional freezing too perhaps – or death. Detective work. The freeze frame is resonant too of Laura Mulvey’s concept of ‘delayed cinema’, a kind of cinematic unconscious visible only when cinema is slowed down or paused, such as a viewer can do easily now, tracking the images which are missed on pause. She gives an example of black extras’ fleeting but significant appearance in the opening credits of Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life (1959). Foreman is simultaneously viewer and filmmaker; invisible viewer within the film, of his father’s archive. This kind of analysis is also reminiscent of the rigorous scientific manner in which Forensic Architecture in The Long Duration of a Split Second (2018) analyse from different angles freeze frames of an Israeli attack on a Bedouin village, or their attempt to show that the chlorine gas cylinders were indeed dropped by the Assad regime in Chlorine Gas Attacks, Douma, Syria (2018) and not placed there in a fake attack, as alleged by the government. They approach found footage, such as taken by mainstream news organisations, using spatial analysis, mathematically analysing trajectories, measurements, even listening for sound cues (such as the sound of a chlorine gas cylinder decompressing). In Foreman’s film, this is a more emotional, as well as political, excavation.

The film recalls too Nathaniel Kahn’s My Architect (2003), a more mainstream and less experimental film, though an obvious predecessor, about the famous architect father he barely knew, Louis Kahn, as he attempts to resolve his feelings towards him. Also, Chantal Akerman’s last film, No Home Movie (2015) which in a more overtly emotional manner details her mother’s experience in World War Two concentration camps and the passing down of trauma from one generation to the next. The Image you Missed can be seen as debt, gift, reconciliation. Here the personal is the political – as we follow the archival footage towards the Peace Process, and the historical reconciliation mirrors the attempted cinematic resolution. I asked Foreman about this – I have known him a number of years which added another layer to my viewing of the film – and he refuted the idea of filmmaking as a therapeutic or cathartic process. But I wonder – personally, I would have found it a difficult, if not impossible, film to make. The film ends with an afterimage: a small boy at makeshift barricades during the Troubles, fires burning all around. And what is the image you missed of the title? It is, on one reading, about the censorship endured by The Patriot Game (letters were sent to all British embassies that they should not promote and in fact should endeavour to suppress the film). In August 1971, in the wake of escalating violence in Northern Ireland, a new law was introduced giving the authorities the power to indefinitely detain suspected terrorists without trial. The Patriot Game shows the impact of street violence during the Troubles and details the emergency powers that the new act accorded, which then included the torture of prisoners. This was condemned in 1976 by the European Court of Human Rights, who ruled that the treatment of the prisoners by the British government constituted torture and inhuman and degrading treatment, but it continued nonetheless, though a later ruling by the ECHR after an appeal by the British government in 1978 found the British government guilty only of the latter crime.

Who is the ‘you’ of the title? Deixis, it could be the viewer, the father or son, or even the British government or indeed the world, which missed seeing censored films like MacCaig’s. The missed image is of course also the father himself: the missing father/missing the father. It is the image between two frames in a cinematic reel. It is the woman who speaks to camera of having been blinded by police forces. It is there in the incomplete narratives. It is the fictional feature film which MacCaig never made, about a member of the IRA – called Donal. At one point during the film, heartbreakingly spoken in voiceover, we discover that in his father’s whole archive he found only one image of his mother and no images of himself. So then it is Arthur too, so intent on documenting everything, getting it all on camera, that he misses taking images of his own son. What he misses is the future.

The sense of something lost, missing, relates to a whole strand of cinema, frequently experimental, evoking cinema’s connection with death and the ghostly, and as a repository of memory. Roland Barthes writes about the still photographic image’s implicit ties with death, with what is past; Susan Sontag believes that the link between photography and death haunts all photographs of people; but cinema also has the ability to appear to bring the dead back to life. (This link between death and the image can be literal too – for example, the use of gelatin, an animal product, to make traditional film). Films focussing on loss and the image tend to point to the fact that much of cinema history has been lost – it has been estimated that as much as 75% of silent films have been destroyed. There are films such as Dawson City: Frozen Time (2016) directed by Bill Morrison, which details the discovery of a cache of silent movies found under permafrost in a former swimming pool in Canada. These are collaged in Morrison’s film (some featuring aesthetically appealing water damage) thereby salvaging history. Other films which perform this restoration of the image include Interior Leather Bar (2013) directed by James Franco and Travis Mathews as they reimagine the lost scene in a gay SM club from the movie Cruising (1980). Guy Maddin takes lost films as his starting point in The Forbidden Room (2015), and reinvents them, some from titles only, others from a fuller description or fragments of film, in a series of nested narratives. Or, Music for a Missing Film (2009), directed by Luis Zubillaga, which traces the lost Venezuelan film, El Huerco (1962), where only stills from the film and the original classical musical score survive. Or Michelle Williams Gamaker, whose art installations restage old films, auditioning BAME actors for roles, rewriting scripts in the manner of Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, attempting to reinstate and foreground those who have been left out or marginalised in film history, and frequently proposing alternative endings for the characters. Miranda Pennell’s The Host (screened by AEMI at the IFI in 2016) comes to mind too, exploring the archive of British Petroleum in Iran, where her parents worked back in the 1970s, and the colonial implications of British ownership of Iran’s oil. Naeem Mohaimen incorporates archival footage from the 1960s and 70s in his three screen Turner Prize installation Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017) about the Non-Aligned Movement, an alliance of Third World countries who tried to present an alternative to the West or Communism, and he juxtaposes this archive with interviews and camera pans through abandoned utopian architecture. Marylene Negro’s X+ (2010), screened by AEMI in 2016, is another interesting example of archival material being repurposed to political and aesthetic effect. Her film, shown in the Pompidou Centre, is a ten documentary mashup, a remix and weave of ten different documentaries from the 1960s and 70s, on Civil Rights, the Black Panthers, the war in Vietnam, all shown at once in a cinematic layering or palimpsest. It cross-references Malcolm X and censorship as well as the idea of collective authorship.

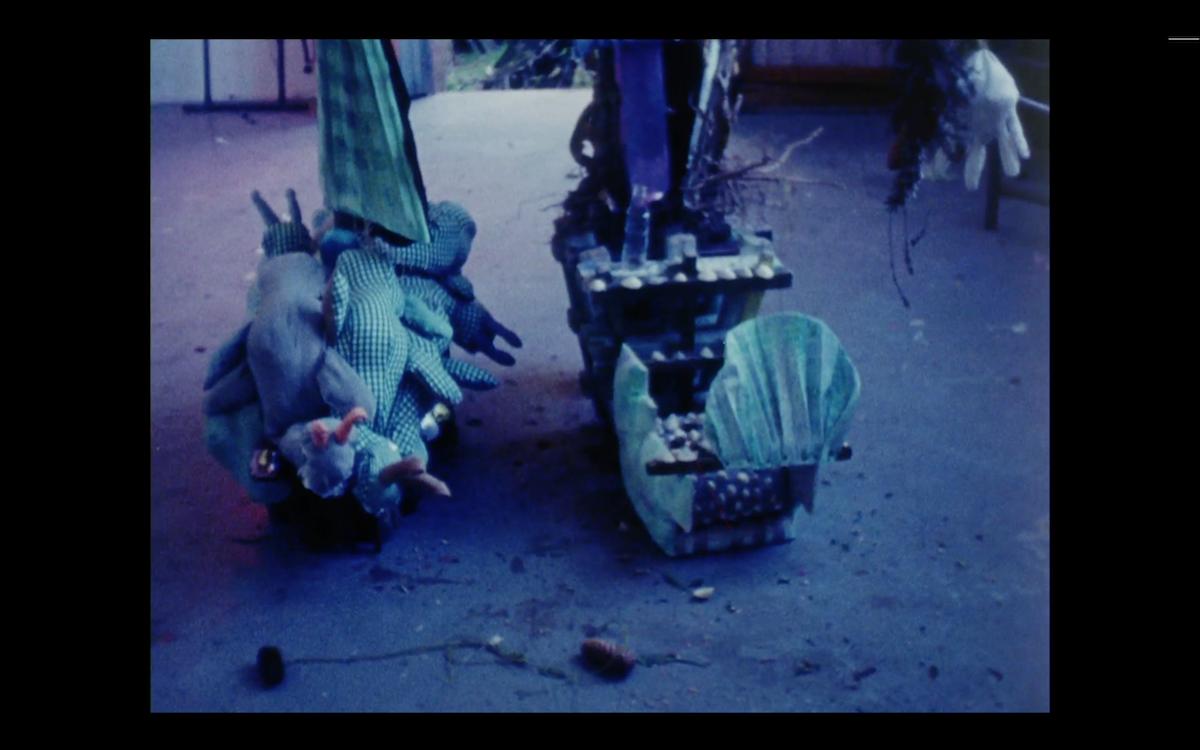

If we perceive The Image You Missed as a healing film, as a film that restores or reconciles something, then other recent films also come to mind. Nathaniel Dorsky’s Arboretum series (2018), 16mm ‘slow cinema’ films of the Botanic Gardens, films in which the camera iris contracts and expands, letting in more and less light, moving towards and away from the flowers, as the films move through the seasons, separated only by film leaders, counting down. I watched the films at Anthology Film Archives, New York, where Dorsky talked of the space of the screen as an energy field, and indeed the experience of watching the films leaves one feeling more as if having done a yoga or meditation class than having watched an arthouse movie. He sees this healing energy as political, that this is what society needs right now. The films of Tamara Henderson, who showed Seasons End: More Than Suitcases at the Douglas Hyde in 2018, and screened her 16mm films along with AEMI at the IFI, also comes to mind: she develops the anthropomorphosis of her strange, anthropological sculptural figures, having them move, dance in Out of Body (2018), giving them subjectivity, or point of view in What’s Up Doc? (2014). The figures, appearing like totems you might more readily find in an anthropology museum from a South Asian island (is this cultural appropriation?) are like ritual objects, death statues. Some have passports, and they travel around the world, from gallery to gallery, their cork feet light, while some, with wooden feet and without passports, have heavier feet than others, and are more weighed down. The figures are full of materiality, peacock feathers, mud, blueberry dye, cloth, ashes, film reflectors, negatives. Some of the figures have secret cameras hidden within them, others bow their cloaks together to make functional darkrooms in Scratched Lab (2018), and a further film is made (but never projected) using the ashes of a scarecrow in Body Bar (2016), a breathing sculpture. This alchemical nature, shamanic suggestion (she talks of the deep red colour her film turned when travelling through the X ray machine at an airport) applies to traditional film in a way that it cannot to digital video. This shamanic quality occurs also in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s double narrative film Tropical Malady (2004), screened at GAZE 2018 by Film Qlub, where the shamanic archetype rediscovers its queer origins: the medicine man or two-spirit person is the progenitor of today’s LGBTQ+. MURDER and Murder (1996) directed by Yvonne Rainer, and screened at IMMA in 2018, depicts a lesbian couple, one of whom is diagnosed with breast cancer. It features interludes with Yvonne Rainer, dressed in an open-shirted tuxedo, showing her own mastectomy scars. Characters in Rainer’s films are frequently split over several actors, and here, during the realist scenes, one character’s mother also appears, more like an externalisation of her childhood psyche than realist narrative. The film depicts healing, but is also increasingly informational as it progresses, to the extent that it becomes uncomfortable viewing, but its purpose becomes at this point educational, to try to save lives.

Pause