The TULCA Festival of Visual Arts put at its heart the theme of ‘Living on the Edge: People, Place and Possibility’. Running in Galway from the 6 – 21 November 2010, this large-scale series of exhibitions, performances, workshops and events offered a view from the periphery. It asked spectators to consider their role in society, and delved into issues of marginalisation, notions of community / sovereignty and the idea of danger or adventure – something inherent, says curator Michelle Browne, in the phrase ‘living on the edge’.

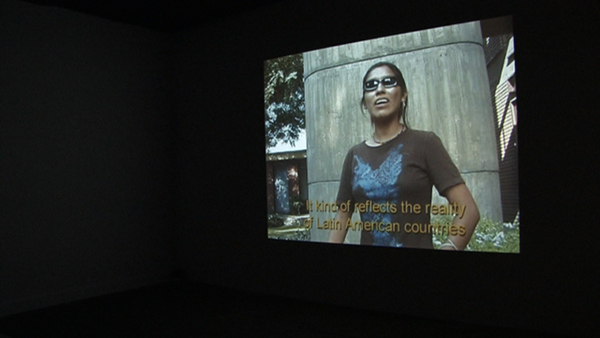

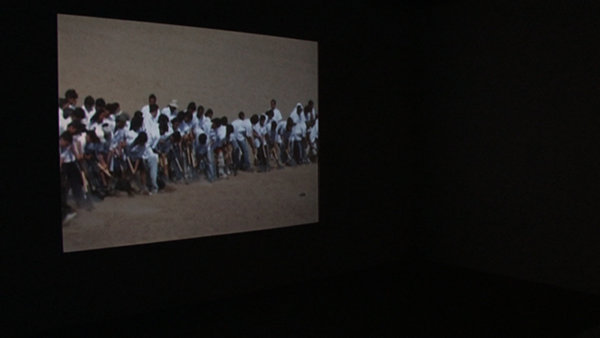

The word ‘social’ appears over sixteen times throughout the TULCA literature with the word ‘community’ featuring five times on one page alone. There is an aching consciousness of the artist’s role in society. In looking at the work of the festival we are reminded of links to previous traditions. The Situationist International movement of the 1950s put forward a theory of the artist as ‘psychogeographer’- one attuned to the study of the “special effects of the geographical environment on the emotions and behaviour of individuals."1 TULCA proposes its artists as psychogeographers of the contemporary climate, with many of the pieces exhibited dealing with cutting-edge issues of modern migration / immigration, economic marginalisation and failing political systems. They address the confines of creating art and its exhibition in the reality of a recession by asking questions of the authorities that promote Galway as the ‘cultural capital of Ireland’ but struggle to provide adequate resources for arts initiatives in the city. This is not, as we are advised by one of Francis Alÿs’ When Faith Moves Mountains volunteers, “art for art’s sake." TULCA advises us to take it seriously, as the current economic climate warrants. In promoting itself as tough and politically engaged, the viewer must ask is this a constructive effort to sell the art-world as a relevant platform for public consciousness or merely a podium for artistic aggrandisement?

In a parallel text developed for the festival, curator and collaborator Annette Moloney discusses the importance of ‘social alternatives’. We now live in an age of uncertainty, with industry no longer providing the sense of security taken for granted in the ‘boom years’. Christopher Gray has said, “the coming society will not be based on industrial production at all. It will be a world of art made real."2 There are issues regarding a lack of control in national and local authority and this spills over into the constructs of everyday living. In a time tinged with jeopardy and anxiety for most, TULCA has identified the real and urgent need for social critique but understands that the role must be undertaken within the confines of a city in recession. The use of ‘alternative spaces’ (Fairgreen Gallery, Docks Shed) throughout Galway offers a different kind of discourse. The theme of the artist as provider – but also as a ‘thinker’ on the edge – runs parallel with the notion of living on the periphery. In its reflective role, TULCA gives an alternative view of a city through the very habitation of the sites. The concept of inhabiting a space in order to comment on its position is a motif recurrent throughout much of the festival – it becomes a world of ‘art made real’. However, it is crucial in examining this concept of habition to appreciate the current fracture in the relationship between artist and authority. By examining notions of marginalisation, TULCA espouses the artist’s regimen of life on the periphery. By asking these artists to regenerate or inhabit empty space within the public sphere, without providing necessary budgetary means, local authorities throw up a significant quandary. There is an underlying tension in the relationship between the two spheres which makes for interesting debate. In the wider world, do festivals like TULCA generate and invite necessary political and economic discourse or are they simply there to ‘paper over the cracks?’

Fiona Woods’ Common photographs pop up in bus-stops and bike-shelters. In their position they are attempting to engage with every participant of the public realm. By exhibiting the imagery in the spaces normally reserved for advertisements to attract weary commuters, Woods asks questions of commonality. There is a commando-style visual ambush with the deliberate placement of the work in these areas promoting a quirky, alternative conception of the space between reality and fantasy. Caroline Doolin’s To Capture the Attention of a Public Looking Skyward also explores the notion of the in-between. Her version of the imagined experience, expressed in the form of a hot-air balloon on the roof of the City Museum and through public performance, lends itself to the theme of adventure promoted by TULCA. The reality and consequence of voyaging into the unknown were also demonstrated here as the piece had to be removed several times due to high winds in November.

Ruby Wallis’ Auto Promenades video and sound installation in the Galway Arts Centre presents two versions of Salthill’s beloved prom. On one screen we see a video of the artist swimming through the bay with the prom and the walkway in sight. The view of the swimmer is juxtaposed with a series of accounts from participants who describe their experience of Galway and the prom while walking the length of the prom. The accounts explore notions of ‘otherness’ and boundaries. There is a sensual quality to the video, with the water and sounds of the swimmer’s effort drawing the viewer into their personal battle with the waves. The climactic sense of journey contrasts nicely with the epiphanical experiences of our other speakers who, in considering their previous adventures, reach a kind of understanding of their place in the world. There is an important account of scattering a friend’s ashes at an unmarked burial ground for unbaptised babies by a woman in the local area. Themes of adventure run concurrently with feelings of displacement, both within the self and society. We get the idea that through analysing the littoral issues of the self we come to accept our role. Our place-ment becomes simply our place. Through making sense of the deliberate action of journey, Wallis’ practice demonstrates the artist, participant and viewer as ‘psychogeographer’ of their own experience.

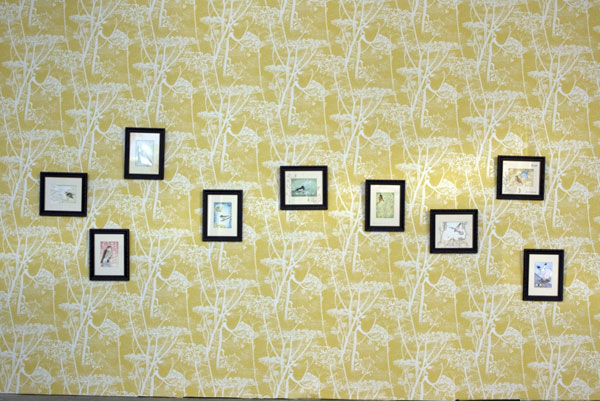

Grouped together in the Fairgreen gallery, Aughty Public Arts Project 2010 is a curated venture within the festival by Áine Phillips. Their prime objective is “to bring live contemporary art to the communities of the region, to generate dialogues (visual, verbal, experimental) around the identity of the place and its future and to expand creative relationships between the Aughty people and artists who are creatively involved in rural contexts." Through a series of pilgrimages, public walks, drawings, sculptural installations and documentaries, the artists explore the core issues with great diversity and energy. There is no sense of a bleeding-heart consideration from the margins. These artists leave the perimeter willingly, choosing to involve themselves and the Aughty tenants in an exploration that spans two counties (Galway, North Clare). Tom Flanagan’s fragmented narrative documentary Aughty: Document 1 sometimes hauntingly traverses the Aughty landscape and is interestingly placed alongside Emma Houlihan’s Aughty Walk: Rural Features and Marie Connole’s Weed or Knotweed? drawings and sculptural installations. Flanagan’s spectral, moving imagery of the natural world juxtaposed with the practicalities of living life ‘on the road,’ reliant on the self for food, shelter and transport, showcases a journey through the natural world that is as important as the beautiful visual dialogue. The Situationist notion of ‘dérive’ is important here – “a mode of experimental behaviour linked to the conditions of urban society; a technique of transient passage through varied ambiances."3 The Aughty Project is a dérive in a rural context. The documentation of the landscape while traversing its acres seems the most suitable form of expression through which to convey TULCA‘s main themes: exploration, people, place and possibility.

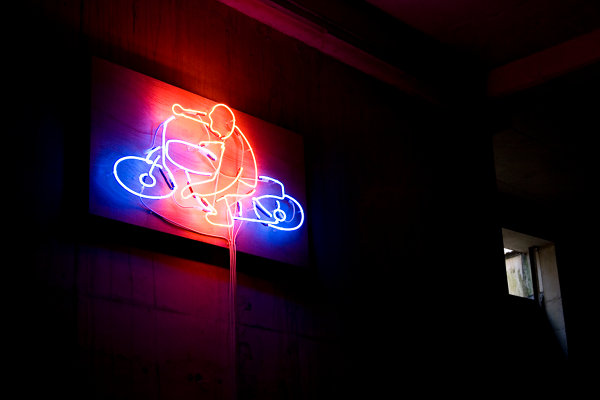

At a time when Ireland has great cause to consider issues of sovereignty it is interesting to see the inclusion of work by Brain Duggan in the TULCA line-up. Using Boris Groys’ proposal of the installation as a sovereign space, Duggan creates an atmosphere of the viewer being in foreign territory. The spectator becomes trespasser, feeling slightly threatened upon entering the space. There is an element of underlying violence and discord in the work. This is thanks, in no small part, to the curatorial decision to showcase the work in the Fairgreen basement. There is no natural light in the space and the concrete flooring, pillars and walls evoke an eerie sense of foreboding. The Situationist theory of spatial development proposes a metropolis of state-of-mind quarters: “a city would be designed to provoke a specific basic sentiment to which the subject would knowingly expose himself."4 Duggan’s ‘city’, with its neon-light sculpture, wooden maze and hypnotic projection all serve to inform the viewer of the artist’s theory of authoritarian control and its prerequisite violence. In the space we also see the Trespass Hoarding films of Aoife Desmond and Seodín O’Sullivan, who investigate relationships between humanity, place and nature in a series of inhospitable ‘hoarding’ sites. Using video, wooden construct and photography, the work nicely mirrors that of Duggan. It also makes clear the important curatorial decision to scrutinise the more threatening and hostile aspects of life on the periphery.

With the inclusion of work by international artists like Francis Alÿs, Marjetica Potrč and Andrea Zittel showcased nicely alongside the local residency productions of Niall Dooley, David Eager Maher and James O hAodha, TULCA 2010 constructed an engaging global and neighbourhood view of what it means to be ‘living on the edge’. Imagery of maps, fabricated globes, falsified / real accounts of events and fervent documented evidence made to engineer a cumulative view of what it is to inhabit and exist in a place, either foreign or domestic. Debord said “that which changes our way of seeing the streets is more important than what changes our way of seeing painting."5 It is with this concept in mind that TULCA attempts to rise to the challenges pressed upon it by both necessity and invitation. The artists are socio-political, engage in socio-spatial arenas and have social mobilisation and movements as their key concerns. While there is the inclusion of art that utilises techniques first implemented in the 1950s and ’60s, TULCA‘s participants have evolved. There is the idea of wanting to showcase work that is intelligent, considered and above all relevant. Crucially, we see the demonstration of an acute awareness of civic anxiety. It promotes a unique formula for change, and advocates a need for social consciousness vital to our habitation of contemporary Ireland.