Tomas Penc & Peter Nash, The Paradise of The Heart,

TACTIC Gallery at Elizabeth Fort, Barrack Street, Cork.

27 January – 8 February 2018

The Paradise of The Heart took place in two derelict buildings in the grounds of Elizabeth Fort, which formally housed Gardaí and their families. The site of the show colours how the work is perceived, the houses are cold, dank and gloomy. The spaces are domestic but abandoned.

On entering the first house, a motion sensor puts in play a computer generated short video loop. It is projected onto a screen installed just inside the threshold of the room on the right. This screen also functions to block further entry. On the screen the image of a dog (a guard dog?) is built-up through various coloured lines of light, a simulated camera moves closer to and around the image that eventually explodes into fragments leaving only the dog’s head behind. Then the loop begins again, the frictionless, tractionless, digital space is challenged by the sound track, which is loud, aggressive and mechanical sounding like chains, nuts and bolts being tossed and churned in a cement mixer. The piece, Barking Dog Seldom Bites by Tomas Penc, exhibits a punning playfulness on the simulations of virtual technology along with a condensed melding of the opposite poles of the “photographic” – ‘drawing with light’ with digital technology.

Upstairs two rooms contain works by Peter Nash. Galvanic Interruption is an installation comprising of twenty-nine small, wooden carved heads. Each head is attached to a short length of wire which is then jammed into wooden sticks of various heights. Periodically these heads ‘come alive’, their chins being connected by a long black thread attached to a motor. Intermittently the motor is triggered and the heads jerk into a parodic simulation of speech. Their chin-tongue-jaws opening and shutting frantically sound like a photocopying machine on its last legs. The heads have a wide variety of expressions: anger, melancholy, bemusement, shock, and acceptance. They all appear as male to me, very obviously hand-made, with no attempt to hide the mechanics of how they work.

The installation Domestic animal takes up the second room, it consists of a sculpture in a vitrine and a drawing on the wall. Both are representations of what appears to be the skeleton of a cat. The sculpture is made of wood, and has a more polished quality than the heads of Galvanic Interruption but again stresses the hand of the artist. The drawing of the skeleton also incorporates text; these could be the musings of the dead cat – who appears to have had a liking for cheap whiskey, lying on the couch and daytime soap operas. Or perhaps the ‘I’ in question is the artist who updates his CV and muses on procrastination. This makes the drawing a paradoxical work, an artwork that records the artist’s blockage around making work.

Nash’s Alternative Anatomies is located on the ground floor of the second building. A small sculpture, an animatronic figure assembled from pine, thread, toy parts and copper wire. This little fellow, a duck-dinosaur, sits inside a vitrine. On a wall is a series of Indian ink drawings, read from left to right and top to bottom the duck-dinosaur cartoon seems to be building himself up from armature to fully feathered creature. There is a sound of swarming bees or perhaps more ominously flies which fills the space.

Nash’s video piece Proposal for a town hall plays on a large TV monitor in the other room. This one- minute stop motion video shows a drawing of an industrial structure, suggestive of both a lookout tower and a diving structure. A little figure emerges, walks to the end of the plank, takes a look and walks back. On his fourth journey he pukes over the edge, the screen goes black and the loop begins again.

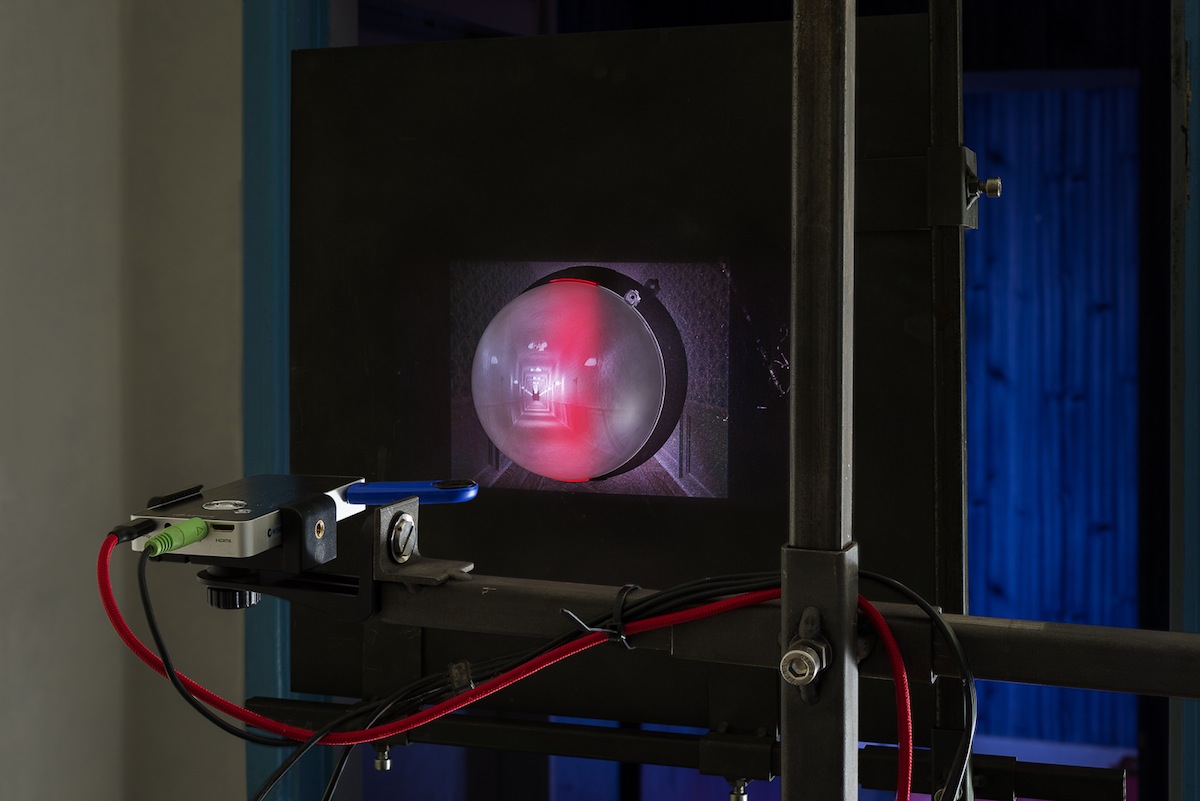

Tomas Penc’s Zukunfmusik is a sculptural installation, located on the 1st floor of the second house, made from concrete, steel, 3D prints and found objects. On the floor are concrete blocks assembled on which two small red figurines seem to be engaged in building up the structure (actually one seems to have given up in despair, his head in his hands). The mould for the building blocks was fabricated using a 3D printer. The other Penc piece, Hidden Potential comprises the swarming sound that seeps throughout the building and the steel structure inside this room’s threshold. This functions as a screen with a peephole through which a taller person than me could look.(I’ve been informed by one such person that there was an image of a hotel corridor, a familiar filmic scene – I imagine the corridor from the Overlook Hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining).

The form of the show complements the description given in the contextualising material. The quote from The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart is a sprawling extract referring to the diverse items a journeying pilgrim comes across on his outward but ultimately inward (returning to heart) journey. The art on exhibit ultimately rests on an inward affinity with either the technology of the past or the future.

Nash’s whittling away on wood is as much a tactic of the present as Penc’s embrace of the virtual, digital design programmes and 3-D printers. This is so because the contemporary is marked by the balancing of retrograde and future techne in answer to the question of how to make in the present. Both poles of craftsmanship exist in contemporary art because ‘the now’ of art practice cannot clearly state what exactly that may be.