Almost a century ago, George Moore delivered a speech advocating artistic shamelessness and the salutary power of shock. “Life is a rose that withers in the iron fist of dogma," declared Moore. If it wanted to progress, artistically, into the modern world, Dublin needed to shake off its puritanical inhibitions and ancient prejudices. To such ends, a flourishing café society was required to administer a healthy dose of immorality. Dublin now has many cafés, of course, as well as a generous share of immorality, but it awaits the arrival of something like the Folies Bergère.

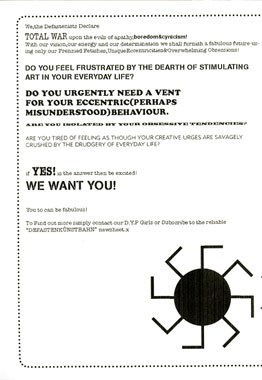

One can discern echoes of George Moore’s plea in the rhetoric of the Defastenists. For example, here is Defastenist Minister for Propaganda & Attire, Padraic E. Moore: “In this age where imagination and individuality is smothered by stifling convention and is systematically mangled into a generic product our gesture signifies a desperate attempt to provoke others into recognising the benefits of Defastening those seat belts of self-restraint and control and nurturing and indulging the fragile creative spark which lies in the soul of every human being!"

Whereas G. Moore decried the piety of Dublin opinion and the philistinism of the Board of Agriculture and Technical Instruction for Ireland, P. E. Moore and the Defastenists wrestle with their own Leviathan of crass commercialism, cynical critics, dull-minded curators, and all-too-pragmatic cultural producers. As a riposte to the well-managed pleasures and homogeneous desires of consumer society, they preach maladjustment and unabashed indulgence in “the fetishes, obsessions and eccentricities which define our creative personalities." In other words, as the juggernauts of postmodernism idle on the spot, for the Defastenists singular desires, productive collaborations and cabaret are the only possible way forward.

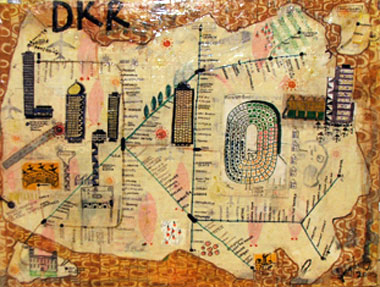

Nevertheless, the Defastenists recognise that artistic endeavours alone are not enough: to safeguard their delicate artistic freedoms a rudimentary state infrastructure must be developed. To this end, they have recently founded their own autonomous nation state, Defastena. This move to establish a “bucolic haven of joyful tranquillity" reveals not a little nostalgia, a longing for a home that is no longer accessible (if ever it was). Romantic poets and philosophers once seized upon the symptoms of nostalgia as “a sign of sensibility, or of newly-minted patriotic feeling" (T. Bewes), and it seems fitting that the Defastenists too, in their more neo-Romantic moments, appear to construe nostalgia as such an individual sickness, marking out the sufferer as one afflicted with aggravated sensitivity – what J. G. Herder called a “tender sorrow, breezy and erotic." But nostalgia is also “a historical emotion" (S. Boym), an epochal symptom, and it is as such that it has been responded to in the modernity that the Defastenists love so dearly. Georg Lukács, for instance, considered “transcendental homelessness" to be the definitive pandemic of modern society. “Happy are those ages when the starry sky is the map of all possible paths," he wrote, “when everything is new and yet familiar, full of adventure and yet their own." This pandemic is still with us, insofar as those ‘happy ages’ remain lost to the alienated and uprooted populace of our capitalist epoch. The Defastenists respond to this ‘transcendental homesickness’ by elaborating what one might call a ‘transcendental homeland’.

Nostalgia is also grief “for the unrealised dreams of the past and visions of the future that have become obsolete" (Boym). The Defastenists grieve for the brave, anarchic enthusiasms of Dada and Futurism, and by grieving they hope to adumbrate the latter’s dreams and visions in the here and now (however different the dreams and visions of these two movements might be).

The Defastenists have a battle on their hands if they want to cultivate the neglected territory of the modernist avant-garde. It appears someone may have got there before them: calls for organised anarchy and workplace insurrection already declare a corporate avant-gardism that “surreptitiously conflates the libertarian, soixante-huitard sense of ‘revolution’ as permanent, ludic change with the ordered socialisation of art propounded by Constructivism" (M. J. Jackson). It is a formidable foe, this growing sector of the global economy wherein the once unique experience of art – in particular the iconoclasm of the modernist temperament – serves as a model of economic life. One wonders if the fledgling state of Defastena can yet muster the forces for full engagement in the long and convoluted war between artists and managers – “one that has been increasingly resolved by a tendency to merge, or even trade places, as the arts become more commercialised while business recuperates their discarded mythology of creative individualism" (M. J. Jackson). There was, and will continue to be treachery, collaboration and heroics on both sides.

All this being said, we might rightly consider nostalgia to be the height of reaction, an easy disavowal of the contradictions and horrors of the past, an act of bad faith, constitutive of the slide towards barbaric oblivion. Can nostalgia be prospective as well as retrospective? Can it scrutinise its own condition whilst it chews through an idealised past? At a time when it seems to have become paradigmatic, can nostalgia still pose an ‘ethical and creative challenge’ rather than be a “mere pretext for midnight melancholia" (Bewes)? If it is to pose this challenge, it cannot turn a blind eye to the contradictions inherent to its object, modernity: and whilst dreaming of how it was, it must also dream of how it could have been. In the maxim, “nostalgia for the future," the Defastenists seem to encapsulate this prospective longing. The power to dream of how things might be otherwise has been cynically manipulated by a market that projects its own ‘revolutions’ repeated ad infinitum to all our temporal horizons. Given this situation, perhaps the innocent power to dream of the future can only be recaptured via decadence in the present; by falling from grace to fall back into grace, so to speak. Without doubt, decadent dreams are central to the Defastenist agenda.

Having recourse to the positive power of dreams is already a sign of desperation. As Walter Benjamin succinctly put it: “The Romantic appeal to dream life was an emergency signal; it pointed less towards the way home of the soul to its Motherland, than to the obstacles that already had barred this way." The impossibility of homecoming except in dream is evident in the real absence at the heart of Defastenist paraphernalia. As noted above, Defastena is a ‘transcendental homeland’ which exists nowhere other than in the bureaucracy and administration that surrounds it, the imagination of the members that adhere to it, and the figures that attempt to represent it. This absence lies at the heart of any nation-state, the existence of which is dependent upon distinctions and delineations that are, for the most part, arbitrary, abstract and ideological. And it is possible that these distinctions might be just some of those obstacles that bar the homeward journey of the soul.

Though still embryonic, Defastena begins to resemble that non-existent yet vividly imagined country, Tlön, which Borges speaks of in “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" – a country that, strictly speaking, does not exist, yet which possesses a language, currency, encyclopaedias, mythologies, fishes and metaphysical controversies. Defastena too boasts its own airline, monarchy, lottery, economy, youth party and ministerial departments. Tlön was protected by its labyrinthine obscurity and its largely ephemeral nature: so too, Defastena. However, and although the Defastenists are, for the most part, inclusive and libertarian in their pursuits, they must occasionally find more robust means to protect themselves. Their police are speedy and resolute, as is shown by the recent blacklisting, during the exhibition itself, of a member suspected of self-promotion and careerism at the expense of Defastenist integrity. The Defastenists seem to understand that, paradoxically enough, a state of anarchy often requires “methodical and disciplined preparation" (W. Benjamin).

The need to prepare a standing army is also becoming clear, as the ‘threat from the East’ grows. For example, Neue Slowenische Kunst (NSK) already has more citizens than the Vatican. The peculiar Western fantasy of Eastern invasion or attack which NSK exploits remains embedded in the popular imagination (not least through the Hollywood disaster film genre, where it blends with alien visitation, conspiracy theories and barbarian hordes). Of course, it is in the nature of nation-states to court a ‘beloved enemy’ of some sort, deriving a certain perverse pleasure from this fantasy of invasion, even when it is realised. Hence, the Defastenists must be vigilant and indulgent at the same time: although threat and counter-threat can be easily exaggerated, with strategic deception employed by all sides, nevertheless, such bombast is essential to what one might call the ‘erotics’ of national growth.

So, the ‘remodernist’ agenda of the Defastenists is not so straightforwardly restorative as it might at first appear to be, especially with regard to their more performative actions and the apparatuses they configure around themselves. Any attempt at prospective nostalgia must negotiate the Romantic-revolutionary shortcut of combining the past with the future, or rather, of retrieving the future from the past: it must save tradition in order to transform it – to give body to its ghosts and attitude to its forms. The Defastenists seem to be attempting such negotiation with infectious enthusiasm and merriment.

What is more – and here the Defastenists show themselves to be a little more post- than re-modernist – between the authoritarian organisation of the state and the libertarian organisation of the group, the Defastenists play out that distinction between two types of desire; the paranoid and the schizophrenic, or in social terms, the fascist and the revolutionary. Desire (or délire, as Deleuze and Guattari have named it) has a collective as well as individual nature. It can be organised roughly into two poles: “the real délire of schizophrenia, centred on flight, and the reactionary délire of paranoia based on the authoritarian structure of the state" (M. Sarup). According to Deleuze and Guattari, the latter is an abstraction and impoverishment of the desire that flows through small, closely-knit collectives of schizophrenic revolutionaries. Again, the Defastenists play with these precarious distinctions, most notably when their futurismo begins to give off the leaden scent of fascismo .

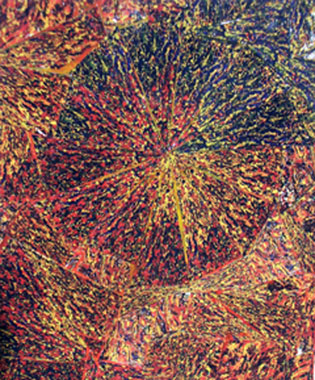

But what about the works themselves? It must be remembered that, as I have tried to suggest, the works here represent only part of a broader project with internationalist intentions. The exhibition comprises paintings, drawings, collages, and photos, as well as proclamations in Tristan Tzara-esque typefaces, newsheets, pamphlets, hastily scribbled thoughts, and the costumed extravagances of the artists and organisers themselves. The exhibition room as a whole is quite mesmerising, a hall of swooning intensities and voluptuous pleasures, one might say, the walls dense with a great coloured tangle of surfaces. From this position, the strength and cohesion of the group is quite evident. Yet, on closer inspection the problems that curators P. E. Moore and Donna Marie O’Donovan faced putting on a group show of such defiantly individual works become more apparent. There is an enormous amount of very different works, and their quality varies greatly. They range from the alarmingly vacuous to the intriguing to the exquisite, and they take as their subject erotica, cross-dressing, animal libidos, zeppelins, pastoralia, the territory of Defastena, love, faeries, angels, psychedelic constructivism, lipschtick, exotica, dreamscapes, Fibonacci rhythms and much more.

Of course, eclecticism was always going to be a dominant feature of such a group as this, but one feels occasionally that the strongest and most peculiar works are somewhat undermined by evidence of a rather self-conscious eccentricity on the part of some participants: an eccentricity that seems a little too conventional or haughty.

There is also something of an over-emphasis on painting, perhaps because it is seen as the privileged medium of individual expression. This is understandable, up to a point. As arch-conceptualists Art & Language themselves have cogently argued, painting is perhaps one of the last strongholds against the total subsumption of contemporary art by those institutions constructed in its name, the simple fact being that a painting is what it is irrespective of its institutional description or display: it cannot be reduced to its discursive validation and therefore offers a unique experience among media. As curator P. E. Moore suggested, it is also a singular method of manual labour, with its own irreducible poetics. This is true, of course, but this labour is culturally inflected and therefore beset with all kinds of prejudices, fallacies and learned spontaneities. Or to put it differently, the sensuous pleasures of painted surfaces always lie over a depth, a “sedimented social context" (A. Bowie) which requires the application of developed judgements, however much this surface might make a direct appeal to our senses. A decade ago, Peter Osborne called for “postconceptual painting" that would strategically deploy its craft in order to revitalise itself, incorporating a critique of itself into its own procedures. None of this is to weaken either painting’s power or that of aesthetic experience, or to suggest that painting should be reduced to the effect of its own concept, it is only to state that the naïve belief in painting as a vehicle of expression, if it is not complicated by the conditions that make it so, is characterised by bad faith and untroubled celebration of received ideas.

All in all, this exhibition was a striking example of a broad-ranging project that is as multi-faceted as it is vital. In its scope, energy and unresolved complexity it is unmatched by anything currently to be seen in Dublin. I shall give the last word to the Defastenists themselves, as they issue a rallying cry that is seldom heard nowadays: “If you hate our ideas or just thoroughly disagree with us: start your own movement/ism as a reaction to ours. This is how progress can be made."

Tim Stott is a critic based in Dublin.

worldlyfl.jpg)