|

| John Byrne: The Border Interpretative Centre (at night); courtesy the artist |

It is probably only those on the outside of a difficult situation who approach it with circumspection. Those inside cultural or political problems can perhaps afford to regard them with less earnest correctness. These days it seems we are all too ready to jump through hoops in our anxious determination to ensure that each situation of cultural difference or difficulty that we encounter is treated with the appropriate gravitas and that no cause is ever given for offence.

It is therefore very refreshing for anyone to encounter John Byrne’s work for the first time, particularly the body of work in this collection, which reflects on the central issues of sectarian difference and political division in Ireland seen from the perspective of a Catholic upbringing in Northern Ireland at the height of the ‘Troubles’.

The first thing that strikes the viewer new to Byrne’s art is that it is often very funny. Byrne takes to himself the role of jester, refusing to be reverent and po-faced in his engagement with issues that so often have had quite deep and devastating outcomes for the people of Ireland. Living inside issues like the sectarian divisions of Northern Ireland is simply part of the management of a life and those at the heart of the matter, day to day, often adopt the most irreverent and cynical modes of making the situation tolerable.

|

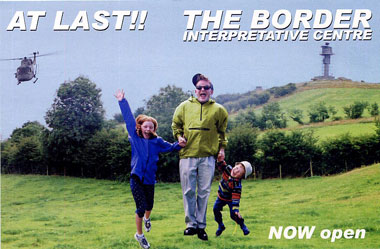

| John Byrne: Postcard for the Border Interpretative Centre ; courtesy the artist |

No one knows more about the hypocrisies and corruptions inherent in the Gordian knots of Irish politics and culture than the Irish themselves, and none but the Irish are more adept at punctuating the pomposities and tub-thumping simplicities of the political and factional leaders, north and south. The jester stands amid these posturings and histrionics and subverts their adopted costumes of gravitas and divisional rhetoric with sugar-coated pills of basic wisdom and deftly aimed barbs of satire, designed to strike at the heart of the issue, often highlighting the inherently crazy and often ridiculous nature of the situation.

Byrne may often be at risk of not being regarded as ‘serious enough’ within an art world that is becoming increasingly socially engaged, because his work can be so very funny. Even his lectures amuse to the point where one tends to feel that something this amusing surely can’t have enough credibility to be truly significant. There is no affected gravitas in Byrne’s work, but that fact by no means lessens it force or its value.

Byrne has used irony, satire, parody over the years in a series of performative and gallery-based photographic and video work almost all of which, at its core, targets the sectarian and political minefield that is Ireland. Much of Byrne’s satire might be thought to be less urgent or necessary in a contemporary climate of post Good Friday Agreement, IRA decommissioning, a newly respectable (and electable), emergent Sinn F é in, and a general downturn in violent activity in Ireland, but such divisions and their legacies do not simply evaporate, and they cling to the culture in deep and subtle ways.[1]

Much of Byrne’s interest in the work in this show arises from his childhood, and it is with a ‘faux naïf’ and childlike directness that he approaches many of these issues. As a child crossing the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic, Byrne expected to actually see the border, or something to indicate where it was, only to be disappointed that something so significant appeared not to exist in any tangible form. This original question was the starting point for him to create work about the ‘border post’ and the whole event of visiting the border as a destination in itself.[2] Ironically, at the opening of the Border Interpretative Centre the border was presented as the only thing that actually united the country. Byrne plays into the hands of those gullible or willing enough to believe the fictions he is proposing, while gently satirising our contemporary expectations that all sites of significance must and will be accompanied by the intervention of a framework with which, or through which, it might be ‘interpreted’.

|

| John Byrne: The Border Interpretative Centre |

There is always in Byrne’s work a desire to punctuate established mores and question accepted convention. The childlike and ironic position he often adopts allows him to ask more directly and pointedly why the Emperor is not wearing any clothes. If the non-Irish person is ever squeamish about dealing with these weighty matters as being ‘life and death serious’ (which they could well have been in the not so distant past), the Irishman is not. There has always been a healthy and perhaps necessary element of cynicism, sceptical reserve and outright parody directed towards the ‘serious’ issues in Ireland. Byrne is, in effect, a rather overt and public part of that tradition.

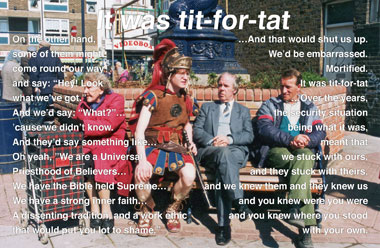

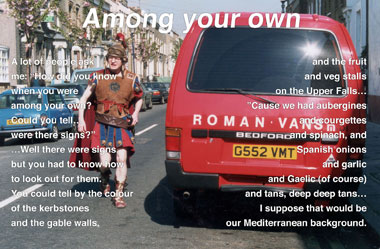

Byrne’s presentation of himself as a ‘Roman’ Catholic is also quite childlike and hilarious, in that he has dressed up as a Roman Soldier from the days of Imperial Rome and engaged people in the street in conversation, the interaction usually arising from their asking him why he is dressed in such garb. The obviously ridiculous aspect of this intervention parallels the ridiculousness of describing Irish Catholics as ‘Roman’, particularly since the practice of the religion has been so different to the Italians’ and was once so threatening to the ‘Roman’ church. The place the Catholic Church has held in Irish society was until recently also quite different from in most other Catholic countries of course: for a long time the sectarian and the political were tightly interdependent in Ireland, due to the enormous influence a powerful church exerted over a pliant population with the full co-operation of a government equally in its thrall – a marriage of convenience that many consider to have severely retarded the cultural development of Ireland. In Belfast, even today the sectarian definition is still one’s primary identifying characteristic.

|

| John Byrne:from Romans; courtesy the artist |

|

| John Byrne:from Romans; courtesy the artist |

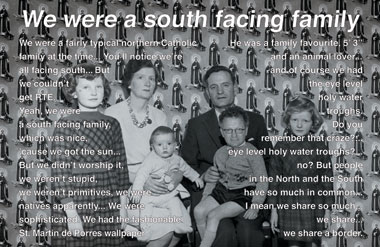

In the image We were a south facing family, Byrne re-creates an old group photo of his family and replaces his little boy’s head with his adult head. This spooky but also very amusing image also then implies that Byrne the boy is also somehow Byrne the man and it is interesting to reflect that the man now plays out and completes or resolves in some ways the fantasies, questions and problems of the child he once was. It is impossible not to laugh at this absurd conjunction, yet at the same time there is a certain note of pathos as one identifies with the ‘child man’ and the strange cultural conundrum that he inhabits. The final line from the text which overlays this image states “…but people in the North and the South have so much in common… I mean we share so much… we share… we share a border.”

|

| John Byrne: We were a south facing family; courtesy the artist |

The photographic series Castles of the border is even more direct, replacing the castles of Ireland, an ever-present reminder of oppression, from the Normans to the ‘folly’ castellated structures of the transplanted English, with the surveillance posts of Northern Ireland, only now being dismantled in the wake of the IRA’s arms decommissioning.

|

| John Byrne:from Castles of the border; courtesy the artist |

Belfast Fashion Week is an actual event, however unlikely it may sound as an event high on the radar of the global fashionistas. Byrne utilises it to create a photographic image of Orange Order stalwarts parading on a catwalk in their distinctive outfits of black business suit, bowler hat, umbrella and orange sash. This ‘costume’ surely is recognisable the world over as the quintessential dress code symbolising ‘Britishness’. Byrne’s re-contextualisation focuses attention on the irony of the ‘displaced’ and transplanted British culture of Northern Ireland, where much of the protestant population clings doggedly to identifiers of being British to the point of parody, just as the ‘British’ of Gibraltar and the Falkland Islands grasp desperately at that same identification. It is yet another stereotypical Irish trope which defines position and identity within the culture.

|

| John Byrne: Belfast Fashion Week; courtesy the artist |

Alongside the video Believers Byrne shows Would you die for Ireland?, a vox-pop analysis of contemporary Ireland in which Byrne catalogues in an unembellished way the responses of people in the street to the stark question, “Would you die for Ireland?” The results are often hilarious (an equivocating Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, raising the greatest laugh from the audience with whom I first saw this work). They are, in their unadorned veracity, a very telling insight into contemporary Ireland and its values. One of the most forceful positive responses came from a recent immigrant, while the response of most native Irish was decidedly equivocal. The Orange Order interviewee maintains the righteous posture one might have expected. It must be said that the initial showing of this work in Kilmainham Jail, as part of an exhibition to mark the two-hundredth anniversary of the death of Robert Emmet, was a more forceful context in which to regard this question and experience this work.

|

| John Byrne: Would you die for Ireland?, video still; courtesy the artist |

|

| John Byrne: Would you die for Ireland?, video still; courtesy the artist |

|

| John Byrne: Would you die for Ireland?, video still; courtesy the artist |

Such work demonstrates the way in which Byrne’s investigations range across the broad landscape of Irish contemporary culture and also reflect the changes and clinging traditions that attend the Irish situation. Ireland today is fraught with a number of issues that arise when a culture is thrust so quickly into a world of consumerism and global capital. There is serious hand-wringing about the values lost, anxieties about Irish culture becoming little more than a realisation of stereotypes and mythologies for the amusement of the tourist trade, and within art, endless debates about what constitutes an ‘Irish’ contemporary art and how valid and appropriate such a question may be now that Ireland’s visual-art scene is also so directly engaged within an international one. Byrne is not alone in centralising much of his work to date at the heart of such matters, on which artists such as Se á n Hillen, and on occasion, Dermot Seymour, Paul Seawright, Brian Flynn and many others have focused, but his questioning usually ranges further, sweeping across the widest gamut of issues currently inflecting all debates on what it might mean to be Irish, and to be a contemporary artist in Ireland in 2006. That this sweep also draws in key issues in contemporary art and culture of a global relevance demonstrates the range and breadth and application of his concerns

In some ways, one suspects, this is Irish work that would travel well. Outside Ireland myths and stereotypes about Ireland still prevail strongly, and Irish contemporary art and its issues still remain very low on the radar of international regard. Byrne’s work may appear at first to be an easy access into such issues, but at its heart lie some urgent critical questioning and a sophisticated engagement with vital issues.

Seán Kelly is a writer, curator and arts project manager based in Hobart, Australia.

|

| John Byrne: Believers, video still; courtesy the artist |

[1] It is also noteworthy in Byrne’s recent work Believers (2005), that he turns his attention to art itself, questioning the values and assumptions of the art world and its institutions and traditions in much the same way he would interrogate cultural norms and values in Irish culture more broadly in his earlier works. This work was created as a commission for Cork 2005 Capital of Culture, and it reflects a timely investigation of the functions to which art may be put within such a context.

[2] The Border Interpretative Centre was the subject of a feature article by Brian Kennedy in Circa 94, Winter 2000.