In our society, it is often that the most useful projects receive the least attention and the most trivial and indulgent receive the most. Celebrity, admiration and distinction are still reserved for singular efforts of extraordinary people, something that leaves the little miracles of everyday life slip by largely unnoticed. Take for instance the completion of Project Kelvin in early 2009, an underwater fiber-optic cable linking Northern Ireland to a transatlantic network. Its effects can’t be limited to the big businesses that need it to move big information: the cable will also bring speedy broadband to the masses and generally encourage a feeling of being up to date. Project Kelvin takes its name from the Belfast-born scientist Lord Kelvin, who played a role in advising the company that laid the first commercially viable transatlantic cable in 1866. That cable, bridging Valentia Island off the south coast of Kerry and Newfoundland, was described at the time as the ‘eighth wonder of the world’.At the cusp of modernity, the generation of 1866 was keen to pay attention to the infrastructures that were allowing society to advance quickly up the technological ladder. It is precisely these same structures that today receive only the briefest mention in popular newspapers and sometimes none at all. The only explanation one could hope to offer is that these technologies have become what Irish artists Ruth E Lyons and Carl Giffney describe as ‘ultra-ordinary’. Iridescence A, a collaborative venture under the moniker ‘The Good Hatchery’, is their latest investigation into these very ordinary phenomena.

Iridescence A is an installation of two parts: outside Monster Truck Gallery and Studios, an array of satellite dishes, radio receivers and CCTV cameras perch on the exterior wall, whilst inside a pair of elegant geometric constructions command the gallery space. These two parts are linked by a tangle of colourful cables that, if we choose to believe, shuttle light and electricity from the complicated apparatus outside into the wooden pods inside. At the centre of each frame is a cluster of fluorescent tubing, the light from which is further dispersed by means of translucent film that splits the white light into a kaleidoscope of colours. The redundancy of a number of the cables points to a deliberate effort to make visible an inner logic or connectivity between the work’s elements. In similar fashion to Rube Goldberg, who made elaborate use of springs, pulleys and household appliances to imagine absurd contraptions for performing simple, everyday tasks, The Good Hatchery appear to take special pleasure in abstracting the functionality of the materials they use. Objects that appear to do one thing are actually doing something else. Iridescence A may give the impression of an autonomous system of technologies, mutually responsive and self sustaining, yet we can never be fully sure if a trick is being played on us. In a sort of artistic sleight of hand, we’re asked to look this way, whereas the real action is somewhere else.

The design of the structures takes its cue from the interlacing struts of electricity pylons. A basic triangular lattice is repeated to form a volumetric surface. This use of repetition and symetry is reminisent of 1960s modular sculpture, but unlike the minimalism of these early modular works, the structures in Iridescence A posess an excess of complexity. They look like platonic solids that have been translated across one hundred different axes of symettry, becoming confidently decorative in the process. Like a cancerous architecture, the sucessive permutations of the basic lattice structure multiply agressively. In certain parts of Ireland, and especially in the midlands where the two artists are based, pylons are the dominant architectural form. Unlike other man made objects in the landscape (houses, factories and petrol stations), these graceful metal behemoths have assumed a mantle of invisibility, whether through indifference or over- familiarity, who knows? It is to this becoming-imperceptible that Giffney and Lyons accord the descriptor ‘ultra-ordinary’. In the same way that ultra-violet can be seen as a final articulation of colour, belonging to the rainbow but extending invisibly beyond it, the ultra-ordinary is part of, yet stretches beyond the regular or customary condition of things.

Whereas inside, the cancerous architectonic forms are the result of successive abstractions of electricity pylons, outside the representations of satellite dishes, radio receivers and CCTV cameras are more concrete and direct. These are the collective infrastructures of global connectivity, technologies that have facilitated the rapid expansion of the public sphere in the case of mass media, the constitution of new communities of interest in the case of TV and radio, and the extension of surveillance and control in the case of CCTV. Again, excess and colour are used to suggest an over-complicated exchange of information. As early as 1899, H G Wells imagined a future where there would be large speaking machines installed on every street corner, chatting out news and propaganda in people’s homes everywhere. The effect of these ‘babble machines’ was to render communication nonsensical, to overload the system through a glut of useless jargon. A quick stroll along any city street will reveal the reality of Well’s premonition. Every house, it would appear, has some awkward appendage pointing skywards, an ultra-architecture made out of transmitters and receivers. What appears to be at stake in Iridescence A is not so much the social consequences of these technologies, but rather the material consequences of their intrusion into the natural and built-up environment.

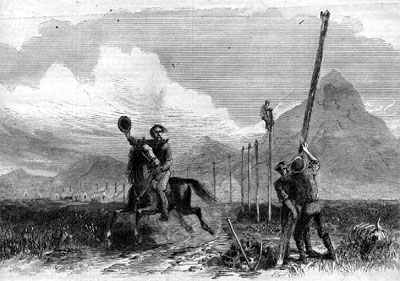

As the first radio stations were growing in popularity in the 1930s, Bertolt Brecht described the radio as “the finest possible communication apparatus in public life, a vast network of pipes…” capable of a new sociality and “…bringing man into a relationship instead of isolating him.” What differs in our relationship to technologies of communication today are not the aspirations we ascribe to them, which have remained much the same from Brecht’s time to ours, but only the ways in which the infrastructures supporting these technologies have progressively reorganized the landscape and the city. Imagine, for instance, the effect of seeing the first cross-continental telegraph wire in America in 1861, its 40,000 wooden poles tracing out a direct line from California to Utah. Imagine the effect of seeing within the landscape the physical wires that were tying the nation together! It is towards this material dimension of technologies that The Good Hatchery diverts our attention. Although referencing the infrastructures of globalization and information technology, what’s refreshing about The Good Hatchery’s work is the manner in which it avoids rehashing familiar or superficial critiques of these far-spanning issues. In an age when critique has become either without consequence or ultra-banal, The Good Hatchery are making good use of a formal vocabulary to make objecthood and materiality the focus of the day.

Claire Feeley is the Glucksman Fellow in Curatorial Practice at the Lewis Glucksman Gallery, UCC, Cork.